Is China now investible? This is the question investors have been pondering since the stimulus package announced in late September.

Measures included interest rate reductions, loans for stock buybacks and a commitment of future fiscal support.

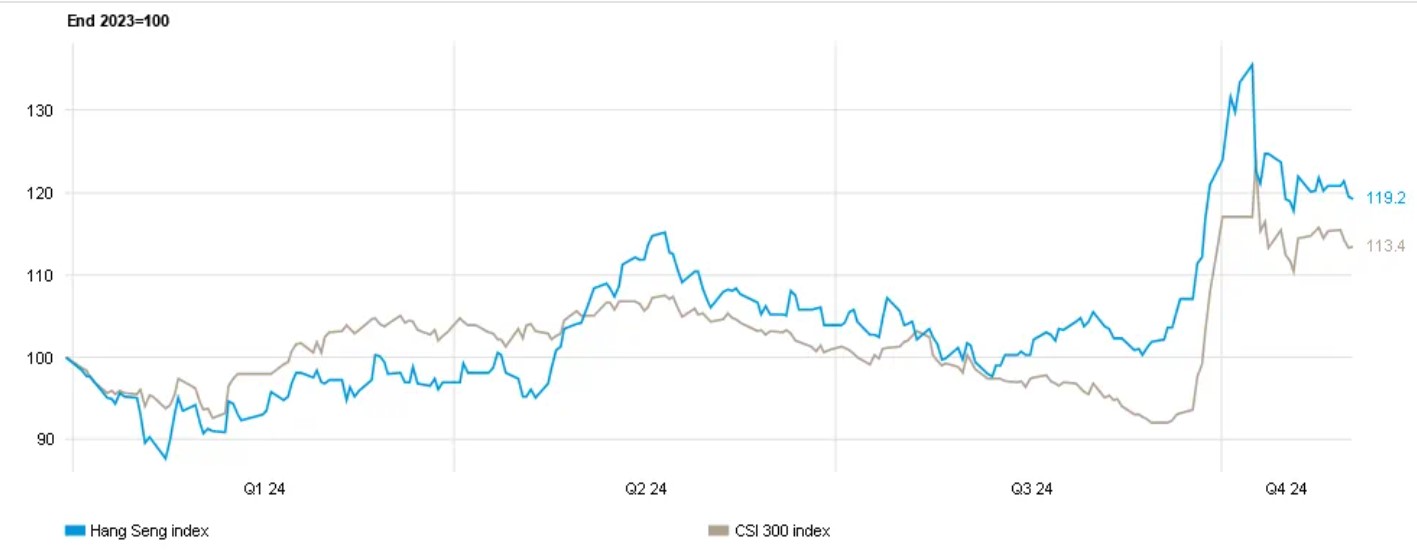

The stock buybacks in particular turbocharged the equity market, with the Hang Seng Index up over 19% year-to-date as at 31 October 2024 and the CSI 300 Index up nearly 14% over the same period.

Why Chinese consumers could be slow to take stock

That something needed to be done was hardly in doubt. China’s consumers are in the doldrums amidst a real estate meltdown, while economic growth is set to come in at just 4.8% for 2024, according to a recent Bloomberg survey of economists, below the official 5% target and well below the 7% or more days of a decade ago.

But while a stock market surge is often seen as a positive signal, the reality is that any wealth effect is not going to change the fundamentals given that less than 10% of Chinese households own stocks, according to a 2020 paper by the School of Economics at Liaoning University.

Compare this with the US, where stock ownership runs at over 60% according to Gallup and a strong market can really make people feel good about their finances.

Investors in China will instead need to view this package more in terms of its effect beyond the stock market frenzy in order to make an informed decision on whether and how much capital to commit to the country.

Chart 1: Stimulus announcement had an immediate impact (29/12/23-30/10/24)

Source: Bloomberg

This assessment is probably best carried out across four main criteria, specifically: sentiment and consumption, productivity, demographics and land reform. As will be seen, what the stimulus does not address becomes as important a consideration as what it does.

Starting with sentiment and consumption, the real estate market as stated remains the stumbling block to consumers feeling better about their personal balance sheets and deciding whether to spend again. The news flow on this front remains grim.

According to official state data, new home prices fell at the fastest pace in over nine years in August 2024, down 5.3% on the previous year.

Cutting interest rates on existing mortgages should therefore have some positive stimulatory effect but ANZ Bank estimates that any savings will convert to consumption of just 0.05% of China’s estimated 2024 GDP, such is the current consumer gloom.

Fiscal stimulus will therefore be required to further encourage consumers and homeowners, but the much-awaited press conference by the Ministry of Finance on 12 October was frustratingly short on the required fiscal details, deferring to later meetings of party officials.

More broadly, consumers will also need to see a more positive economic culture and tone in order to restore their old spending habits. While most would not have been directly affected by the crackdown on corruption and graft in recent years, the overall message on curtailing conspicuous consumption has hit home a bit too much.

LVMH reported in July that its sales in Asia – including China but not Japan – fell by a cool 14% in the second quarter, deteriorating from a 6% decline in the first. No one is feeling confident.

Chinese EVs are no longer on a charge

Productivity is another area which could restore China’s economic growth nearer to the old 7% per annum days. But the stimulus package itself is another sign of interference in the economy, with no evidence that state-directed investment into favoured sectors is going to be re-considered.

Electric vehicles (EVs) provide a good example of the current problem. Surplus EVs are currently gathering in weed-infested car parks across the country according to Bloomberg, as no fewer than 100 EV manufacturers compete for limited business at home while facing protectionism in overseas target markets.

This misallocation of resources hits productivity and growth by crippling unsubsidised but more dynamic businesses in other sectors.

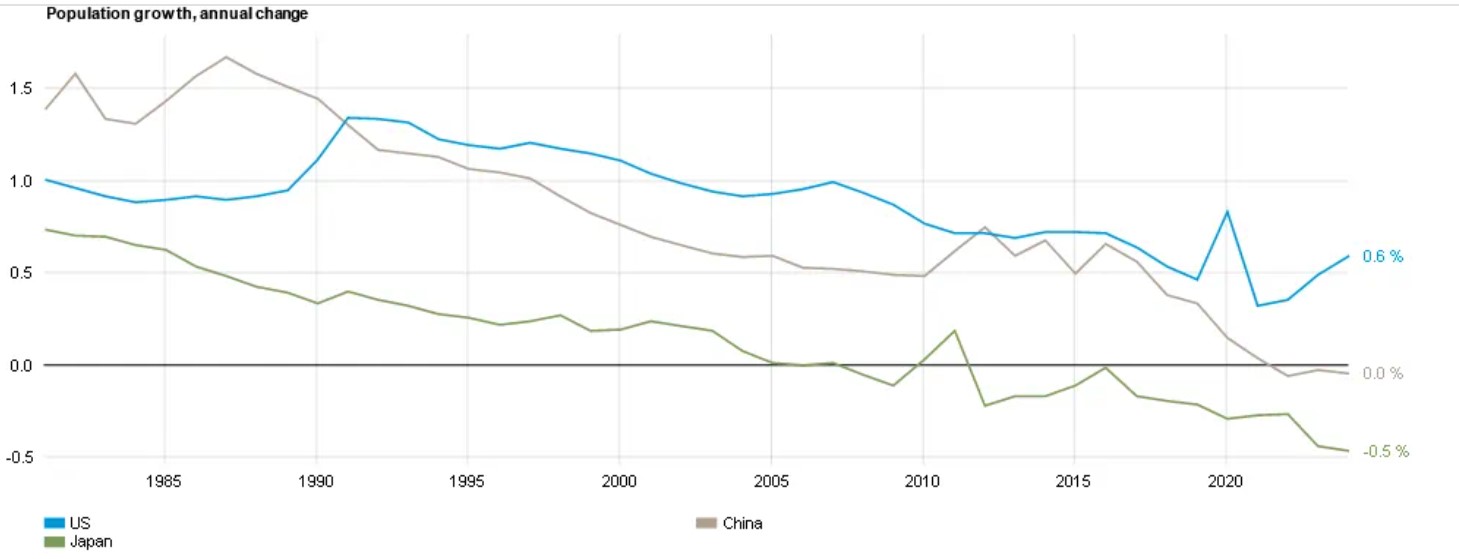

Demographics were also left unaddressed. Beijing is reluctant to publicise precise figures showing how Chinese women have been having fewer children even since the official abandonment of the infamous one-child policy in 2016.

Curiously, the National Bureau of Statistics stopped releasing annual data on fertility rates in 2017, but the International Monetary Fund publishes top-line population growth figures and is now estimating that by the end of 2024, China’s population growth will have outright ground to a halt.

Barring a productivity revolution – which appears unlikely – a declining working-age population is going to be bad news for the economy over time. In a candid admission, the National Institution for Finance and Development conceded in June that “As the population peaks, China is showing signs of Japanification”.

How reforms to farm ownership laws could boost growth

Not unrelated, land reform was also studiously ignored by the latest stimulus pronouncements. China has two distinct legal regimes for urban and rural land. The former is owned directly by the state and is leased to businesses and individuals on contracts of varying duration according to allocated usage.

These contracts renew by default, giving effective tenure similar to private property ownership. Rural land, however, is owned by collectives and can only be traded among members of the same collective, which effectively keeps farmers from trading land or using it as collateral for borrowing, limiting in turn the opportunity to allocate capital to new opportunities and forcing many rural Chinese to cities.

Meng Xiaosu, a retired official who shaped China’s property reform policies in the 1990s stated at a forum earlier this year that “If rural land is made tradeable, I believe it can push the Chinese economy back to an annual growth rate of more than 8 per cent for over two decades”.

Framed in this way, the stimulus package increasingly looks like a wasted opportunity.

Chart 2: China’s population growth looks set to grind to a halt

Source: Bloomberg, IMF

It is of course easy to be a sceptic, and it should be acknowledged that China’s recent policy pronouncements at the very least represent a concerted effort to drive growth in a way which has not been seen since 2008.

The country’s stock markets could well continue to enjoy the heady combination of cheap valuations and better-than-expected stimulus efforts by the government, which has so often jolted depressed equity markets around the world in the past.

Any relief on the Chinese real estate front will doubtless be very welcome to beleaguered Chinese consumers. But the long-term impact of the stimulus effort remains somewhat unclear given that it is not addressing the totality of China’s longstanding challenges.

Even as details of the fiscal package are awaited, this simply does not have the feel of one of the seminal great leaps forward that characterise Chinese socio-economic history.

Deng Xiaoping’s ‘To get rich is glorious’ slogan and associated liberalising reforms feel very distant from today’s more dour ‘Common prosperity’ and ‘New productive forces’ themes with their associated state-directed economic management.

New rules, purges and arrests of entrepreneurs make for an uncertain business environment that discourages the sort of private enterprise that is the lifeblood of dynamic economies in Asia and the rest of the world.

In addition to this, China presents investors with geopolitical risk around the thorny issue of Taiwan and its relations with Russia, while the US election will almost certainly see more tariffs imposed on Chinese goods as America-first style policies win favour on both sides of the political divide.

For investors, all this speaks of modest but watchful participation in Chinese markets at the index level, rather than a fresh outsized commitment.

This is less unambitious than it sounds. Should China’s economy really start to turn around, its stock markets will still provide plenty of opportunities to participate more meaningfully at a later stage.

Julian Howard is chief multi-asset investment strategist at GAM Investments