The ESG ecosystem has three groups of players – the data providers, the asset managers and index providers (data consumers), and the asset allocators. Unfortunately, it is a rigged game with only one clear winner – the data providers that sell ESG ratings.

Current demand for anything ESG allows asset managers and index providers to charge more for ESG than for plain-vanilla products, but there is the additional cost of buying data, hiring quant analysts to dissect and organize the data, and spending money on marketing.

There are second-order benefits to asset managers like reducing the emphasis on short term performance (“Don’t mind how badly value is doing, rather look here at how great our ESG positioning is!”). The asset allocators, and ultimately their clients, are most likely the losers as they are financing this “feel-good” ecosystem, with little evidence supporting the idea that ESG investing generates consistent outperformance.

The market for ESG data is expected to grow by 20% and reach $1bn in 2021 as per a recent research note by Opimas, a management consultancy. The growth in data spending is mirrored by a significant increase in the assets under management (AUM) in global ESG ETFs, which have increased by $38bn to more than $100bn in the first eight months of 2020, according to data from ETFGI, a data provider.

It is precisely because of the strong momentum of the ESG industry that investors need to be cautious in evaluating ESG data, which has become increasingly complex given the abundance of options. As of today, there are more than 600 ESG rating frameworks as reported by the think tank SustainAbility, which makes it almost impossible for investors to evaluate all of them. Furthermore, some ESG methodologies result in strong sector and factor biases, which can lead investors to unknowingly double up on the same risk exposure.

Having said this, not all data providers have the same methodology, and the complexity of ranking companies provides an opportunity for differentiation. In this short research note, we will evaluate the ESG data set of a well-known provider by asking the simple question: what are we buying and what are we selling when using this data?

Defining the ESG universe

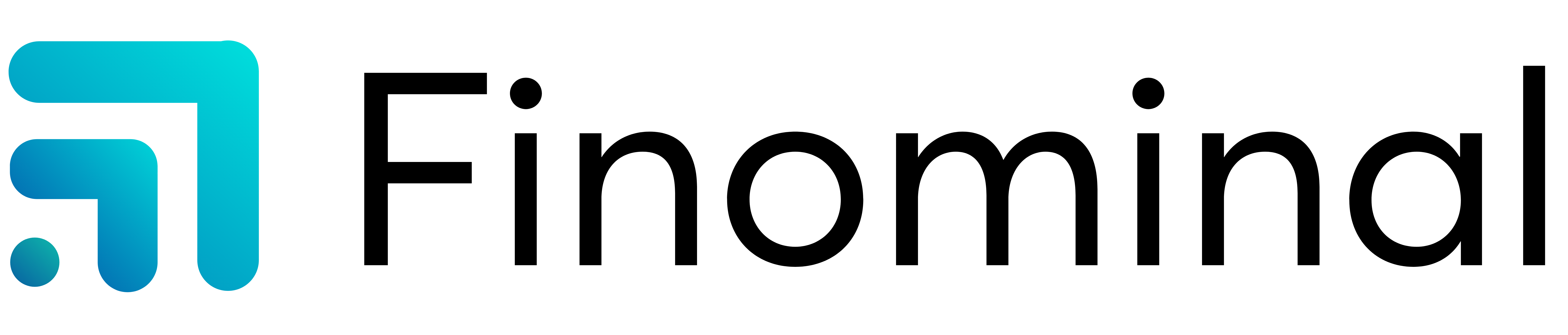

We will focus on US stocks in this analysis, where the number of companies with an ESG rating in the data set has increased from 20 in the year 2000 to approximately 800 in 2020, covering almost all stocks in the S&P 500.

Somewhat surprisingly, the average ESG rating has doubled from 25 to 50 over the same period. An ESG enthusiast might hope that all companies have become better corporate citizens and therefore earned higher ESG ratings, but that assumption is too naive.

The increase in the average ESG score is explained by more data becoming available over time and the stocks being evaluated from today’s perspective, which is only possible by adjusting the historical ratings. Unfortunately, this implies that year-to-year comparisons are not that useful and ratings should only be evaluated on a cross-sectional, relative basis within a year, which increases the complexity of using ESG data (see Graph 1).

Comparing good versus bad corporate citizens

Asset managers and index providers can use ESG data in various ways of constructing ESGcompliant portfolios. Historically, many product providers excluded stocks with low ratings, but that has become less popular in recent years as the approach leads to large tracking errors. For example, the majority of US stock market returns since 2010 are explained by a handful of stocks, primarily the FAANG stocks. If one of these few stocks would have been excluded due to a low ESG rating, then returns would have been significantly lower, which most investors would have struggled with.

Weighting stocks by their ESG scores creates similar issues, which explains why ESG is now typically incorporated on a sector level. However, although this minimises tracking errors, it does lead to exposure to undesired sectors like energy.

Asset managers can only hope that clients do not look too closely at the breakdown by sectors in marketing materials as that would infuriate some of them. Fossil-free is not always 100% fossil-free.

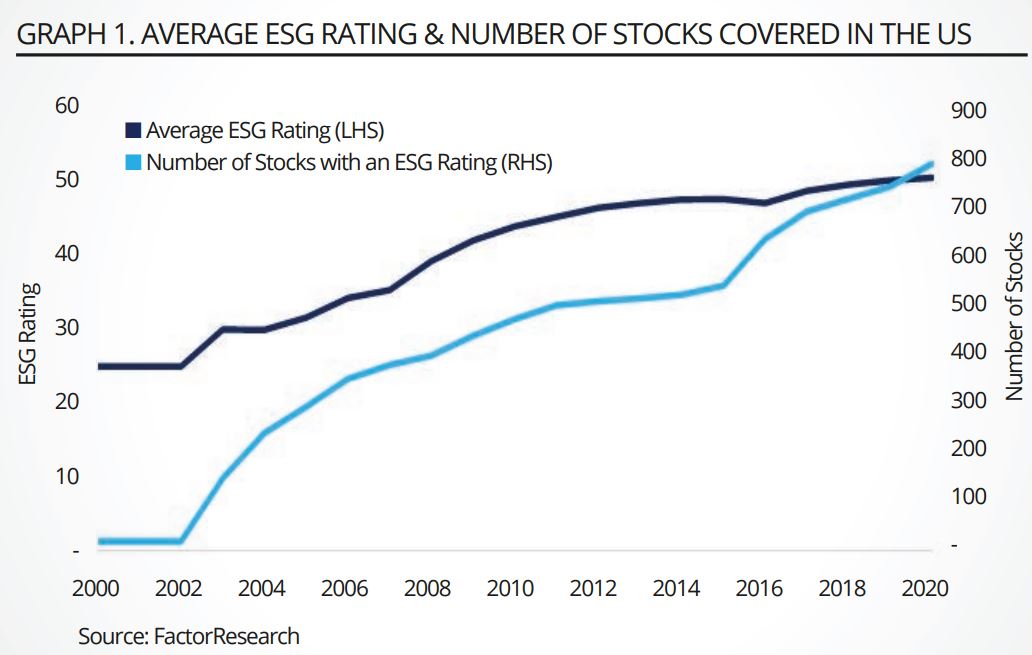

In order to analyse the ESG data set, we separate all 790 stocks into quartiles based on their ESG ratings and calculate key fundamental ratios based on the most recent financial data.

We observe that companies with high ESG ratings generated lower EPS and sales growth, but also featured higher operating margins compared to stocks with low ratings. Furthermore, good corporate citizens are more profitable, but also more leveraged. Based on these ratios, it is difficult to identify a common thread between stocks with high and low ratings (see Graph 2).

Source: FactorResearch

Size and valuation biases

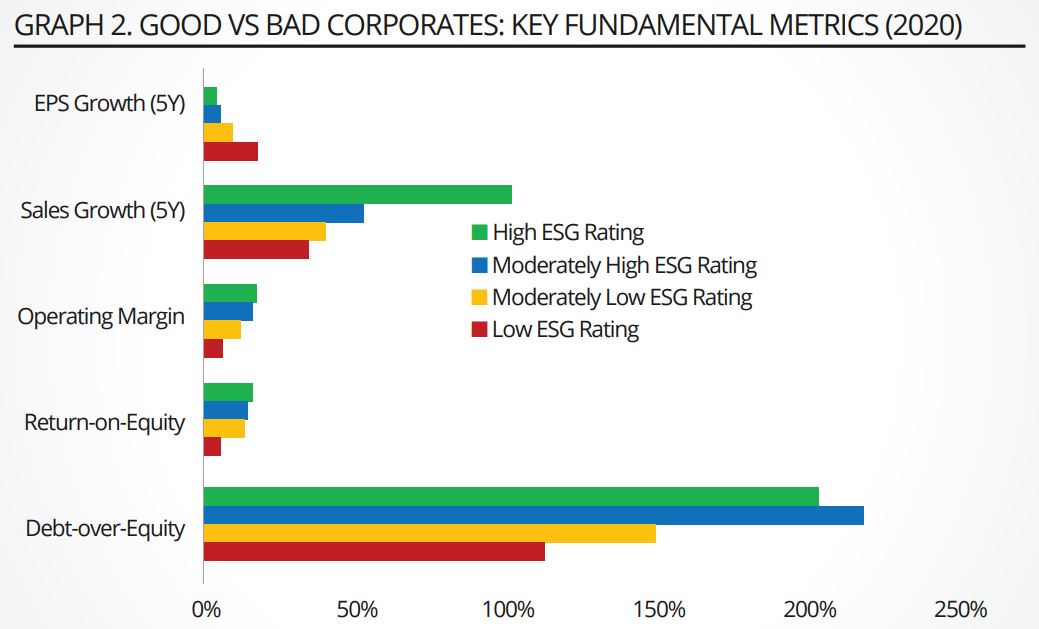

Next, we analyse the market capitalisations and equity valuations. We observe that stocks with a high ESG rating feature larger market capitalisation, but also lower valuations on average. The negative exposure to the size factor, which is defined as going long small and shorting large caps, is not surprising as large companies have more developed corporate governance and social standards than smaller ones.

They also have dedicated investor relations staff that can focus on fulfilling complicated ESG reporting requirements. However, the positive exposure to the value factor, i.e. buying cheap and selling expensive stocks, is unusual as stocks trading at lower valuations typically represent companies in trouble, where there is little money available for achieving a high ESG rating. In most ESG data sets stocks with the highest ESG ratings are expensive, which is also a reflection of biases towards sectors like technology (see Graph 3).

Source: FactorResearch

Investigating sector biases

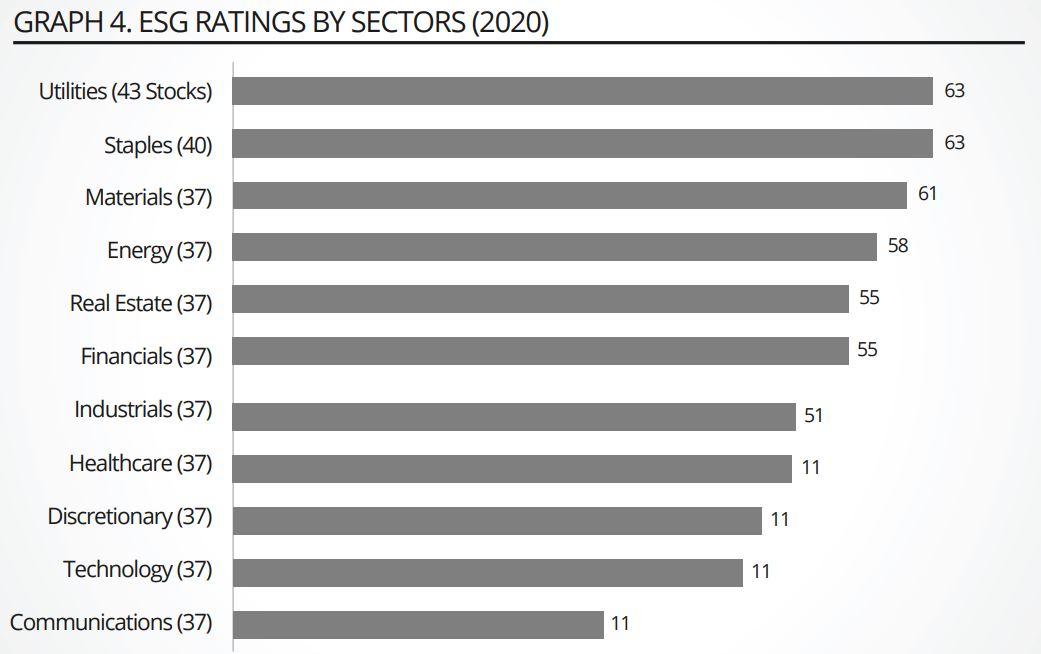

Calculating the average ESG rating per sector also highlights a somewhat odd picture as sectors like energy and materials feature high average ratings, but these stocks are typically at the bottom given low environmental scores. It is worth noting that this data provider calculates ESG scores on a range from 0-100 and sector-neutral, but it is difficult to explain why utility stocks have an almost 100% higher ESG score than communication stocks on average.

Perhaps this is an indication of companies starting to game the ESG ecosystem, e.g. by disclosing more or only selective information (see Graph 4).

Source: FactorResearch

Risk and returns

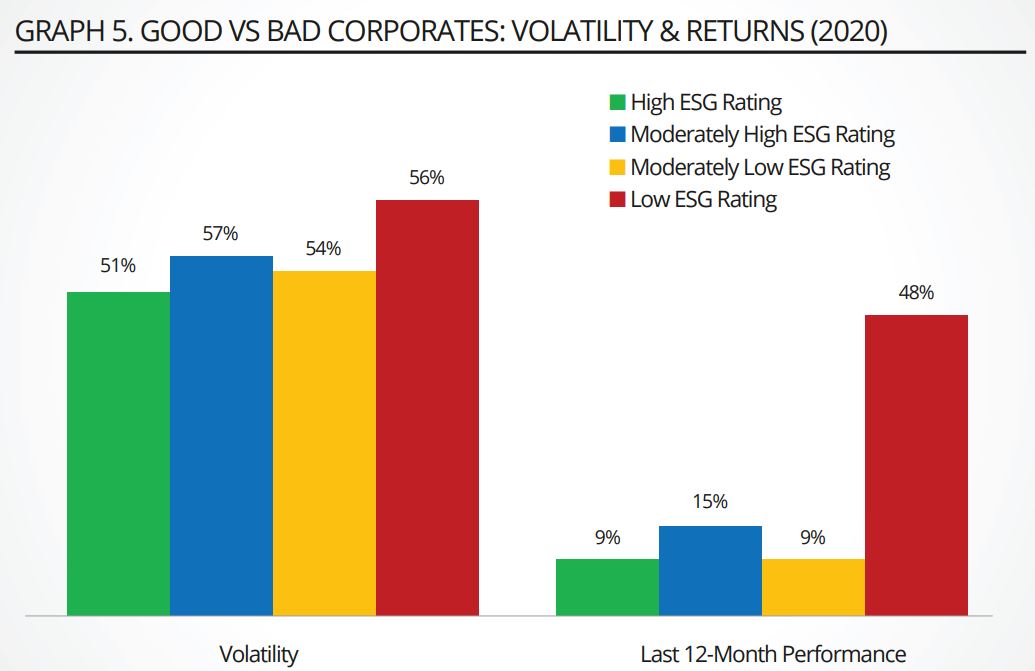

Finally, we review the annualised volatility and 12-month performance of the companies ranked by ESG scores, which highlights that stocks with the lowest scores were more volatile, but also generated the highest returns. Given that we are looking back only one year, this should not be regarded as particularly representative of ESG data (see Graph 5).

Source: FactorResearch

There is little research that suggests that ESG generates excess returns over the longterm, which data providers and asset managers have acknowledged. Therefore, the focus when marketing ESG has shifted to using ratings in risk management, where a frequent argument is that companies with low ratings have a higher risk of corporate disasters. Naturally, it would be great to be able to avoid stocks like BP before their oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010.

ETF Insight: Consistent ESG data needed for sustainable investing to avoid greenwashing issues

However, ESG scores can be compared to credit ratings, which have been available for decades and do not seem to have high predictive powers.

On the contrary, credit ratings of corporates and governments tend to be downgraded after material events and therefore represent a lagging indicator of corporate riskiness. It is difficult seeing why this would be different with ESG ratings.

Further thoughts

Going back to our original question: what are we buying and what are we selling in this data set? Well, the companies with the highest ESG ratings are large companies trading cheaply and featuring positive as well as negative fundamentals.

Overall, we are somewhat dazed and confused by this characterisation, however, that is not necessarily a negative. It seems you are buying ESG aware companies, although not in the way that it was intended.

Most ESG data sets feature the same sector (long technology, short energy stocks) and factor (long quality, short value) bets, which can lead investors to be exposed to more of the same risk, e.g. by holding a technology and an ESG ETF. In fact, the portfolio characteristics of this ESG data set could be regarded as positive from a factor investing perspective given the tilt to large-cap value stocks.

Nicolas Rabener is founder and CEO of FactorResearch

This article first appeared in the Q4 2020 edition of Beyond Beta, the world’s only smart beta publication. To receive a full copy,click here.