The COVID-19 lockdown is a unique event that will be studied in textbooks decades after the fact. Record unemployment, broken supply chains, unprecedented government spending, and a significant drop in GDP are just some of the events the world has experienced so far in 2020.

After an initial drop of more than 30% in February and March of this year, the developed equity markets have recouped that loss, racing higher, seemingly disconnected from global economic reality.

A handful of tech companies has fuelled this unprecedented equity growth. The tech-dominated Nasdaq Composite closed nearly 17% higher on August 24 than its pre-crisis peak, up almost 27% from the beginning of the year, and amassing an enormous cumulative gain of 410% over the preceding 10 years. As of July 31, the US equity market valuation has reached the bubble-level valuation of 29.6x in terms of price to cyclically adjusted most-recent 10-year earnings (also, known as the Shiller P/E ratio) and 3.5x in terms of priceto-book ratio (P/B).

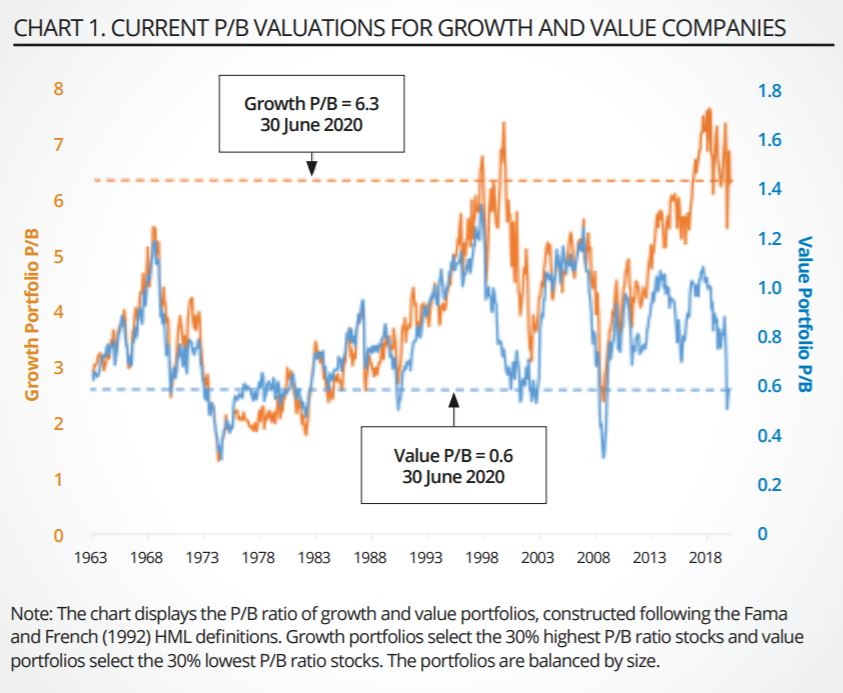

The growth (many of them, tech) companies today are priced at some of the most expensive, bubble-like levels in history. At the same time, crisis fears have pushed value companies’ valuations to some of the cheapest levels in their history. Both growth and value have hit these extreme valuation levels before, but never at the same time—the spread between value and growth valuations is the widest it has ever been!

Past experience has shown that the resolution of crisis uncertainty has been the best time to be invested in risk strategies. If history is an accurate guide, a return to economic stability combined with the historically unprecedented spread in valuations implies a very attractive value investment opportunity.

The new tech bubble?

Given this environment, do we consider equity markets as verging into bubble territory? Yes, we do. Rob Arnott and his co-authors in Yes, It's a Bubble. So What? defined bubble conditions as occurring when the gap between current valuation and historic average valuation of a stock or asset class is at an extreme.

The market constantly creates single-asset microbubbles, isolated examples of extreme mispricing. Wider bubbles are much rarer occurrences. The tech bubble in 1999–2000 falls into this category. Chart 1 shows current P/B valuations for growth companies (left axis, in orange) and for value companies (right axis, in blue). The current P/B valuations for growth companies are on par with the tech-bubble period of two decades ago.

Source: Research Affiliates

Today, a handful of tech stocks, what we call the FANMAGs (Facebook, Apple, Netflix, Microsoft, Amazon, and Alphabet/Google), have collectively appreciated more than tenfold since 2007, representing about 26% of US stock market capitalisation (as represented by the S&P 500) and 60% of the Fama–French growth portfolio as of July 31, 2020. The FANMAGs’ valuations are responsible for the record-high growth valuations. Without these six stocks, the S&P 500 over the same period would have been lower by a cumulative 3,000 basis points.

Applying our definition of a bubble to the FANMAGs, Microsoft and Apple do not fit the strict definition, because only aggressive, rather than implausible, assumptions are necessary to support their high valuations. Others, however, present a more nuanced case as Rob Arnott and his colleagues explain in Bubble, Bubble, Toil and Trouble. Nevertheless, these six stocks are largely trading at valuations nearly as rich as they have ever traded—as is true of the US equity market as a whole, whose current Shiller P/E of 29.6x compares to its historical average of 17.1x. We would recommend not betting on the momentum’s continuing or trying to score a big win with a short position!

The extreme concentration caused by these and other highflyer bubble-territory tech stocks impacts market cap-weighted indices. These indices are moving into bubble territory too as they take on increasingly larger positions in these stocks, replicating the concentration of the indices they track. Investors should be wary.

The value anti-bubble?

After nearly 14 years of value’s underperformance compared to growth, value investors are understandably re-examining their commitment to value investing. The corollary to this, however, is that value companies (whose valuations are shown in blue in the chart) are trading today at some of the most depressed valuations in history.

Rob Arnott, Campbell Harvey, Juhani Linnainmaa, and I in Reports of Value’s Death May Be Greatly Exaggerated explore several common narratives offered as explanations of value investing’s death as a robust investment strategy. We conclude that this time is not different. Because growth companies are trading at their most expensive valuations in history and because value companies are trading as cheaply as they have ever traded historically, value’s 14 years of underperformance relative to growth can be largely explained by widening valuations.

Of course, today, we are in the middle of one of the worst crises in recent history. The sectors hit by economic hardship and uncertainty have depressed valuations. To learn how factors may react in the forthcoming economic recovery, my colleague, Ari Polychronopoulos, and I analysed factor performance in recessions and subsequent recoveries. We considered the performance of the five most popular factor strategies – value, low volatility, quality, small cap, and momentum – over the six bear-market recessions and recoveries (measured as two years after the market’s trough) in the United States since 1963.

In the downturns, low volatility was the only factor offering almost universal protection. All other factors were a coin-flip at best. In the subsequent recoveries, value, quality, and small-cap strategies did demonstrate quite consistent outperformance, winning in five-out-of-six or six-out-of-six of the recoveries we studied. In the downturns, fears of economic uncertainty have tended to lower valuations for these strategies, thus embedding a significant fear premium in their prices. As economic uncertainty is resolved, however, the prices for these strategies tend to spring back, handily rewarding the patient investor.

Today’s unique environment combines fear-driven depressed valuations for value companies and the widest valuation spread between value and growth companies ever seen. Wide dispersions are not new. In the past, the valuation gap was mean reverting, narrowing to levels that drove value’s outperformance. As economic uncertainty around the current crisis is resolved, and if history is an accurate guide, these unique circumstances may prove to be very attractive for value investors.

Vitali Kalesnik is head of research, Europe, at Research Affiliates

This article first appeared in the Q3 2020 edition of Beyond Beta, the world’s only smart beta publication. To receive a full copy,click here.