The internet has thrown off many cultural artefacts. It has created memes, legitimised instant gratification and boosted callout culture.

But perhaps the most lasting cultural legacy of the internet has been the expectation that everything should be free.

Spotify did it with music, Google with journalism, Pirate Bay with movies, Amazon with shipping, Robin Hood with brokerage, Revolut with currency transfers. On the internet, free stuff is the starting point of every business model.

ETFs, an internet-era technology, increasing come with the same expectation.

The latest to fall victim to this expectation has been State Street, which announced yesterday that it would cut the fee on its flagship ASX 200 ETF from 0.19% down to 0.13%, which comes pretty close to free.

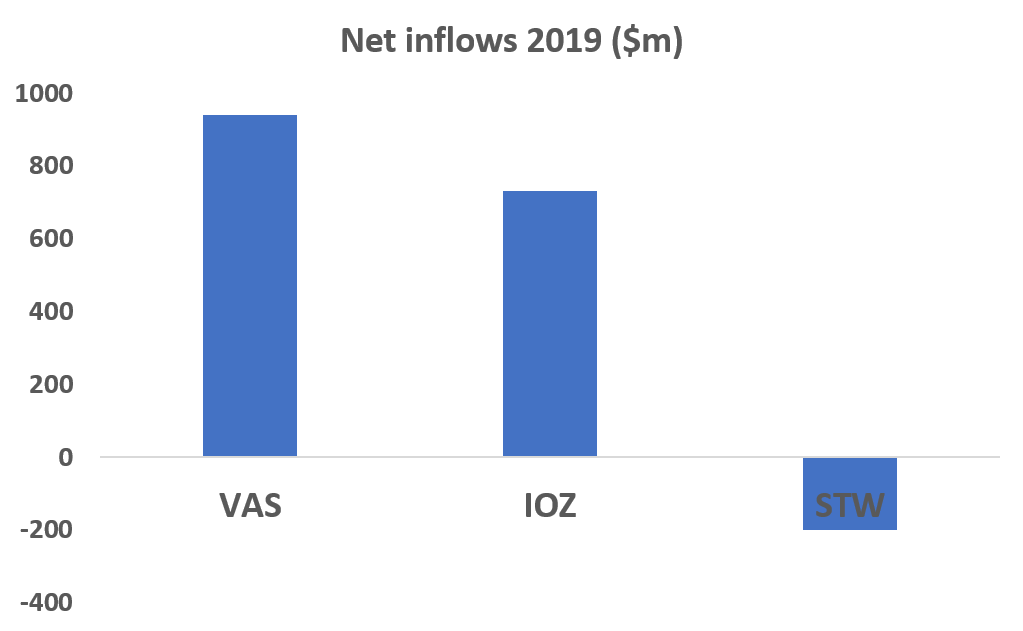

State Street held off from cutting fees for several years. But contrasting its fund’s fortunes with other ASX 200 trackers in 2019, the company must have concluded STW had become harder to sell thanks to its fee.

STW's top competitors - VAS and IOZ - saw substantial inflows in 2019. Source: Ultumus, ETF Stream

State Street’s decision has been cheered by ETF buyers. But there is reason to think that fee cuts in Australia are coming too hard and too fast. Worse: if the ETF industry has the profits sucked out of it this early in its development, Aussie investors may end up worse off. How?

Building any kind of successful business is difficult. But building an ETF business is more difficult than most. Because fees are so low to begin with, ETF providers need $1-2 billion in assets just to break even. Getting there takes years and incurs millions of dollars in cash burn.

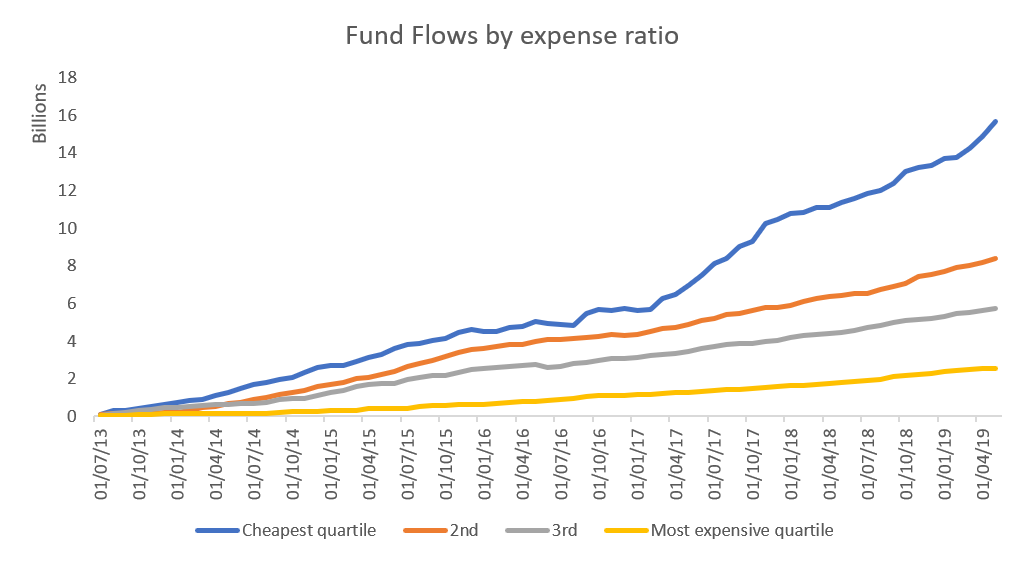

Old ASX graph showing fund flows by expense ratio.

And once you get to break even, it is no Valhalla. Margins are constantly under pressure. Because the ETF industry is a transparent market with limited intellectual property protections, clever products get copied and at a lower price.

It is for these reasons – cost and risk – that almost every ETF provider in Australia has the backing of a deep-pocketed foreign company.

If the profit calculus was always stacked against ETF providers, the fee war makes it worse. This calculus will impact investors, too, and for a simple reason: if ETF fees fall too far too fast, asset managers will not list ETFs at all.

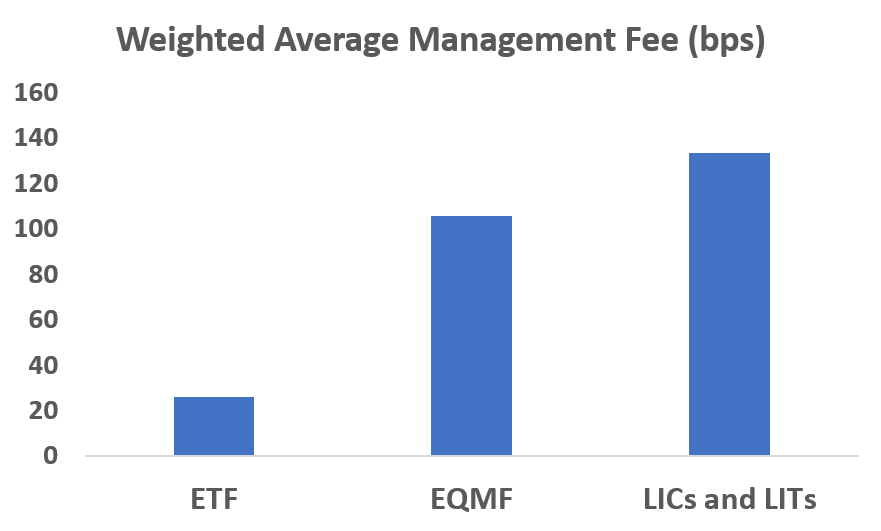

Instead, they will offer EQMFs (sometimes called “active ETFs”) and LICs – as these have higher profit margins. Recent decisions by Fidelity, Janus Henderson and Schroders to list EQMFs suggest this is precisely what is happening.

This all threatens to make investors worse off as ETFs are cheaper and better performing than these other kinds of fund.

Australian investors are already well-served when it comes to ETF fees. The average expense ratio worn by investors buying ASX-listed ETFs is around 26 basis points, ASX data indicates. Putting this in perspective: the average LIC fee is 133, the average EQMF fee is 106. The numbers cited here are favourable to LICs and EQMFs, as they exclude their performance fees.

Source: ASX, ETF Stream

Aussie ETFs are also cheap compared to ETFs in other parts of the world. Canada’s ETF industry is four times the size of Australia’s. Yet its ETF fees remain higher.

So what, then, is to be done?

For investors and advisors buying ETFs, it can be useful to remember that there is such a thing as paying too much attention to fees. Some of the higher fee ETFs – like VanEck’s MVW, iShares IOO, and BetaShares AAA – have been better performing than their cheaper competitors. In some instances – not all – you really do get more when you pay more.

Australia's best ETF: Vanguard's VAS or VanEck's MVW

For ETF providers, it might be best to simply ignore the fee war and the media horse it rode in on. Much of the fee war has been media-driven. Yet thanks to the internet, big media outlets have never been weaker. You can ignore them if you want.

Internet giveth, internet taketh away.