An unprecedented rush to environmental, social and governance (ESG) ETFs began last year as their large-cap-growth-tilted exposures appealed to the pockets and principles of established and newcomer investors alike. Now, over seven months since the start of the fabled rotation to value, has ESG enthusiasm been tempered and what impact might its rise have on asset allocation and wider society?

The stickiness of ESG assets was first displayed during the height of the coronavirus pandemic volatility in 2020, where, despite European ETFs booking their worst month of outflows on record last March, ESG ETFs saw positive inflows of €730m in the month, according to data from Morningstar.

On top of this, ESG strategies outperformed their parent indices, with the MSCI World ESG Leaders index beating the vanilla equivalent by 1.3% in Q1 2020, while 76.9% of ESG exposures outperformed the S&P 500 and MSCI Europe index, respectively, over the same period.

However, many have been quick to warn that these disparities can be explained by differentiations in sector weightings.

For instance, Vincent Deluard, director of macro strategy at StoneX Group, said: “ESG funds’ outperformance in 2020 was lucky: the sector is tilted towards tech and healthcare monopolies and avoids the employee-intensive firms which suffered the most from the pandemic.”

Thankfully for ESG advocates, the main draw of ESG ETFs is not – and never should be – their potential to achieve returns alpha.

So far this year, large-cap-growth-overweight strategies have often underperformed versus equivalent exposures with a bias towards small-cap and cyclical sectors.

A prime example of this is Europe’s largest S&P 500 ESG ETF, the Invesco S&P 500 ESG UCITS ETF (SPEP), which has returned 15.5% so far this year. Compare that with the Xtrackers S&P 500 Equal Weight UCITS ETF (XDEW), which has returned 18.6% over the same period, according to data from ETFLogic.

Despite this, ESG ETFs have continued grabbing larger stakes in European investors’ portfolios.

So far in 2021, approximately 40% of all inflows into European ETFs have gone into ESG strategies, owing to landmark events such as investors swapping out their traditional core equity exposures for ESG equivalents and the stand-out popularity of individual products such as the SPDR Bloomberg SAD US Corporate ESG UCITS ETF (USCR) which has seen $5.5bn inflows so far this year, according to data from ETFLogic.

The ESG roster now claims 11% of all the money in European exchange-traded products (ETP), with 96% of these assets classified as Article 8 under the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) and more SFDR Article 9 launches set to come, according to Bloomberg Intelligence.

Overall, then, the rotation to cyclical stocks might see ESG ETFs underperform in the short-term but a death knell for the green investing epoch, it is not.

As Peter Sleep, senior portfolio manager at 7IM, said: “The value rally may slow investors’ enthusiasm for ESG at the margin, but not by much.

“Many ESG indices are designed to have low tracking error and not outperform or underperform by much.”

While avoiding drastic underperformance will be a comfort to recent ESG converts, the staying power of this asset class depends primarily on the idea that positive change can be affected by how investors allocate their assets – and this idea has now gained significant momentum.

“Nothing is stronger than an idea whose time has come,” Deluard, said, quoting the words of famous author, Victor Hugo, in his report titled ESG investing: A special (and critical) report.

“The ESG movement, once a niche for hippies and tree huggers, has become the most powerful force in global capital markets: the 3,038 signatories of the UN Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) manage more than $100trn, the European Commission passed the Non-Financial Reporting Directive, and ESG funds posted record inflows in 2020 thanks for their strong performance,” Deluard added.

Unintended but ingrained consequences

So, the cyclical regime change may not pose an existential risk to the ESG platform but if it takes some of the steam off the green investment fanfare, investors might see it as an opportunity to reflect on what further encroachment of ESG might look like – and what the movement needs to do better.

At present, the predominant application of ESG in Europe tends to lean towards environmental issues, which in turn means ETFs in the product class are likely to underweight carbon-intensive sectors and smaller companies, which are less likely to report on ESG performance.

While the scoring systems responsible for this approach rightly reward initiatives such as stricter staff travel and materials recycling policies, they perform inadequately in scoring companies based on many behaviours which define their impact as corporate citizens, Deluard said.

StoneX Group’s Deluard: ESG ETFs more hype than hope?

As such, an unintended but inbuilt feature of much ESG scoring is to reward companies whose activities end up having a negative effect on the social fabric of the societies they operate in.

One such activity is monopolistic behaviour. ESG high-scoring tech firms such as Microsoft, Apple and Intel have to-date avoided antitrust enforcement as their “free” products enhanced consumer welfare; they have used non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) and non-compete agreements (NCAs) to lock employees and suppliers in place; and now enjoy cheap capital from the ESG movement while other sectors have their investments restricted.

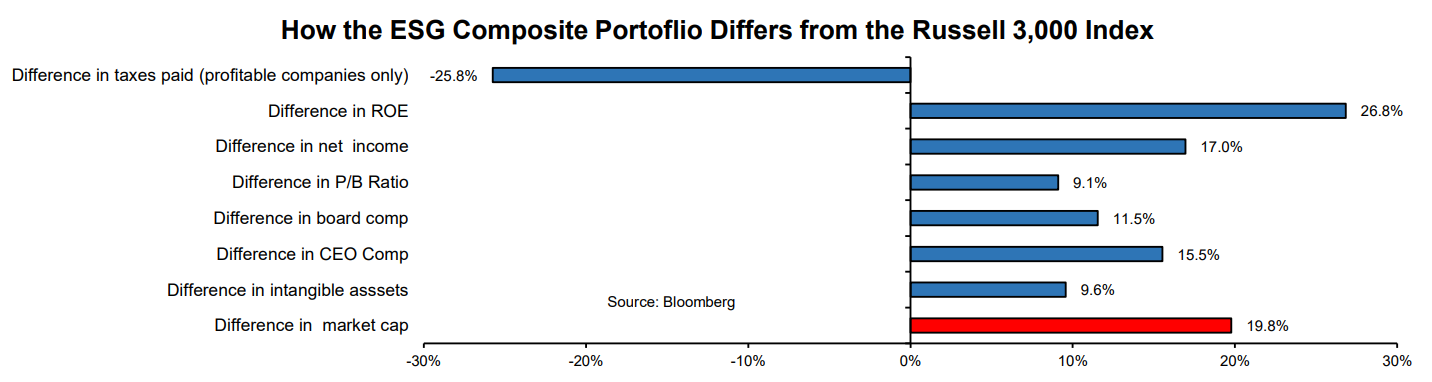

Compounding this, smaller companies are less likely to have the time, capacity or incentives to disclose their ESG data, Deluard said, while scaling emissions in line with market cap means not only do tech firms benefit from economies of scale but also their ability to outsource the emissions within their complex supply chains. The result of these dynamics can be seen in index composition, with the average market cap in an ESG ETF being 20% larger than in the traditional Russell 3,000 index.

While not ideal, these firms’ outsized influence would be less of an issue if they acted as virtuous citizens. Unfortunately, this is not the case, as set out by many high-profile accounts of scant tax contributions.

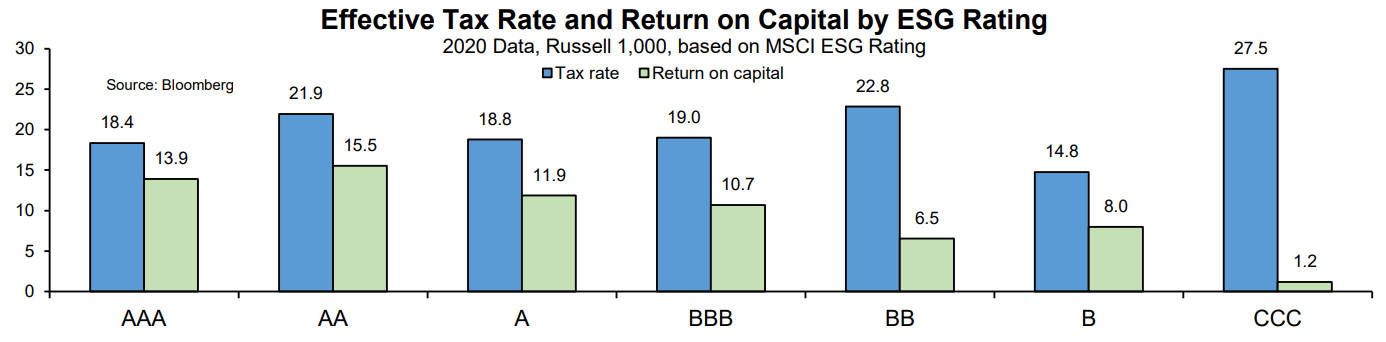

Deluard identified a positive correlation between firms’ high return on capital and high ESG ratings. Regrettably, there is an inverse relationship between companies’ ESG ratings and their effective tax rate, with CCC-rated companies paying an average of 27.5% in taxes – almost 10% more than the amount paid by AAA companies.

And this is entirely symptomatic of ESG scoring, with only five of MSCI’s 1,945 ESG metrics relating to taxation and skewing towards large tech firms most able to configure their tax liabilities favourably.

“The companies which rank highly in ESG metrics tend to be globalized tech and healthcare monopolies with a small physical footprint, few employees, and a lot of intangible assets,” Deluard noted. “They can easily arbitrage differences in tax regimes between the many countries they operate in and reduce their tax liability via transfer pricing and by locating their intangible assets in the most favourable tax jurisdiction.”

While some might argue companies have a fiduciary duty to be efficient stewards of capital, the premise of ESG is to reward those who go beyond Milton Friedman’s austere vision of companies being unfeeling, profit-making entities.

Also, the regular counter to the point about companies not paying their fair share of tax is that they provide jobs, which are themselves a social good.

Unfortunately, this is also an area where tech behemoths fall short. In fact, the average company in an ESG ETF composite portfolio employs 20% fewer people than the average Russell 3,000 company. Likewise, the 15 companies most overweighted by ESG indices employ just 1.9m staff combined, compared with the 15 most underweighted companies, which employ 5.1m.

Deluard said this bias against high employment is an inherent feature rather than a fault in ESG’s current design.

“The more humans a firm employs, the more reprehensible behaviours will be committed: robots and algos do not engage in sexual harassment, do not get injured on the workplace, and cannot be discriminated against.

“Second, many of the policies which are rewarded, such as community spending, covering gender re-assignment services and having a supplier diversity program are so costly than they can only be implemented by high margin monopolies.”

Naturally, he said, job satisfaction will be a lot higher among small teams of highly paid software engineers or scientists, than among elderly care workers or Walmart cashiers.

Overall, ESG already needs to be praised for not just bringing important conversations to the fore but encouraging us to fundamentally revaluate the role of the corporation.

However, while the cyclicals recovery may not unseat the rise of ESG investing, it should at the very least make us consider the merits of the ‘old economy’ and what it does better, especially in ‘S’ and ‘G’ terms, than the ESG usual suspects.

Sources of optimism

Sleep added that traditionally high-polluting sectors such as mining and energy will have an integral role in our lives for decades to come – and in the case of metals and natural gas, a crucial role in the green transition.

As such, he said, it is positive when these industries are included within sector neutral ESG indices, which do not outright exclude parts of the economy but rather overweight the players in each industry which perform best on a data providers’ chosen metrics.

Intuitively, an investor might note that while tilting to higher-employing and higher-tax-paying ‘old economy’ sectors might favour the social element of ESG, it requires a trade-off regarding a portfolio’s performance on environmental issues.

On this, Sleep said issuers might choose to apply carbon offsets to their ETFs, or companies might apply these to their own operations internally. And, while Sleep noted this kind of mechanism is in its infancy, last week saw a major breakthrough with the launch of the HANetf S&P Global Clean Energy Select HANzero UCITS ETF (ZERO), Europe’s first carbon-offset ETF.

Another doubt many investors have is on the sincerity of ETF issuers’ promises on ESG enforcement. Indeed, not only did the big three index fund providers – BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street Global Advisors – voted against or abstained from all 16 shareholder resolutions calling for action against deforestation between 2012 and 2020, their business models are designed to minimise costs and the best way to do this is to avoid creating friction.

This attitude is also reflected in BlackRock’s company makeup, with the company owning 10% of all US shares and only hiring 45 professionals for its investment stewardship team.

Their solution is to perform what Deluard described as “low cost, low value” voting, by looking to proxy advisors such as the Institutional Shareholder Service Global Research team, which, as of June 2017, had seen its 270 research analysts take part in some 250,000 votes.

Gladly, there has also been progress in this area, via the entrance of a new San Francisco hedge fund upstart, Engine No.1. Having taken Exxon Mobil to task on its emissions and having three of its senior level nominations elected to Exxon’s board, the activist group of former BlackRock employees launched its own ETF, the Engine No. 1 Transform 500 ETF (VOTE), which promises to apply the same active approach to engagement which earned the company its place in the spotlight.

This, Sleep said, acts a sobering reminder of the large ETF issuers not backing up the right words with corresponding actions.

“This pressure originated from a small company […] with ETF issuers hanging on to its coat tails,” Sleep continued. “If the ETF issuers were serious about ESG, why did they not propose these motions?”

While keeping these kinds of questions in mind, developments such as sector neutrality, carbon offsets and more active engagement could all see ESG ETFs better-represent ‘S’ and ‘G’ considerations and encourage companies to set proactive targets for better ESG performance.

The next step, Deluard said, is for relatively minor changes to be made to ratings metrics including rewarding companies with a high headcount and vice versa for mass lay-offs, rewarding companies paying their fair share of taxes without arbitraging inter-subsidiary transactions and punishing those involved in antitrust investigations and political lobbying.

These steps, Deluard concluded, will help ESG move from a green screening activity and towards being a metric that rewards the best corporate citizens.