What does ‘sustainable’ mean? While fund advisers or providers are required to ask investors about their sustainability preference – as well as their risk tolerance, under MiFID II regulation – they are also required to elucidate sustainable products while “avoiding technical language”.

Those sustainable products are classified under the EU’s SFDR either encompass highly sustainable funds (Article 9) or somewhat sustainable funds (Article 8) while everything else (Article 6) is therefore implicitly unsustainable.

Presented with a choice between, on the one hand, funds that are sustainable to some degree and do no significant harm, and on the other hand, funds that are implicitly unsustainable and harmful, it would be surprising to see investors choosing the latter. What is perplexing, however, is what they are choosing.

Asset managers are nervous

The “billions chasing contested ESG funds leave insiders ‘mystified’,” bemoans one headline. Puzzling and puzzling ‘till their puzzlers are sore, blindsided “industry insiders confess they do not understand why investors are not being cautious” anymore.

Even as Article 8 outflows hit €29bn in Q3 and €120bn for the year, Morningstar data shows, Article 9 inflows reached €13bn over the same quarter and €29bn for the year.

Spooked by the greenwash associated with broad-brush ESG funds, investors are fleeing Article 8 for the greener pastures promised by dedicated impact or thematic sustainable funds.

But does Article 9 plug the gap? Their popularity is unsurprising but dark-green funds are not secure in their status. Those “industry insider” jitters are justified. Absent clarity from ESMA, asset managers are “struggling to guess” what qualifies as “sustainable”, prompting pre-emptive action. In the time since Q3 data were published, the SFDR Green Reaper has been hard at work.

Last week, BlackRock, UBS Asset Management and Invesco announced plans to downgrade Article 9 funds housing tens of billions of dollars. Article 9 has two problems. The first and widely accepted version is that the category may not be as sustainable as it appears.

Some questions, such as whether weapons qualify as ‘sustainable’, should not be up for debate and yet are for at least 165 Article 9 funds. Morningstar warns that fewer than 5% of Article 9 funds “target sustainable-investment exposure between 90% and 100%”.

Our own analysis yields some suspect activity under their bonnet, including hundreds of millions in exposure to Coca-Cola, which does quite a bit of harm, actually. Hundreds of millions may not sound like much but it is not insignificant in the context of a relatively compact €400bn in Article 9 assets.

And that is the second issue. In terms of impact, it is harder to find pure – and established, and liquid – ‘green’ companies than it is to find ‘complicated’ companies. Blame an economy in the early stages of change. Blame an economy that is complicated. Supportive fiscal policy, rapidly advancing innovation, and blended finance solutions all help. In the interim, however, there is a lot of interest in a rather small universe.

From our own analysis, the 18 largest Article 9 funds by AUM represent €86.9bn, or around 20% of the total pot, a share that grows as the number of funds shrinks. By median average, their top 10 holdings represent a chunky 32% of the total portfolio size. These are concentrated funds! And they sit in the eye of a perfect storm.

If money keeps pouring in, and funds keep dropping out, then flows will accelerate towards the remaining highest-impact thematic funds, many of which have a necessary bias to smaller cap companies.

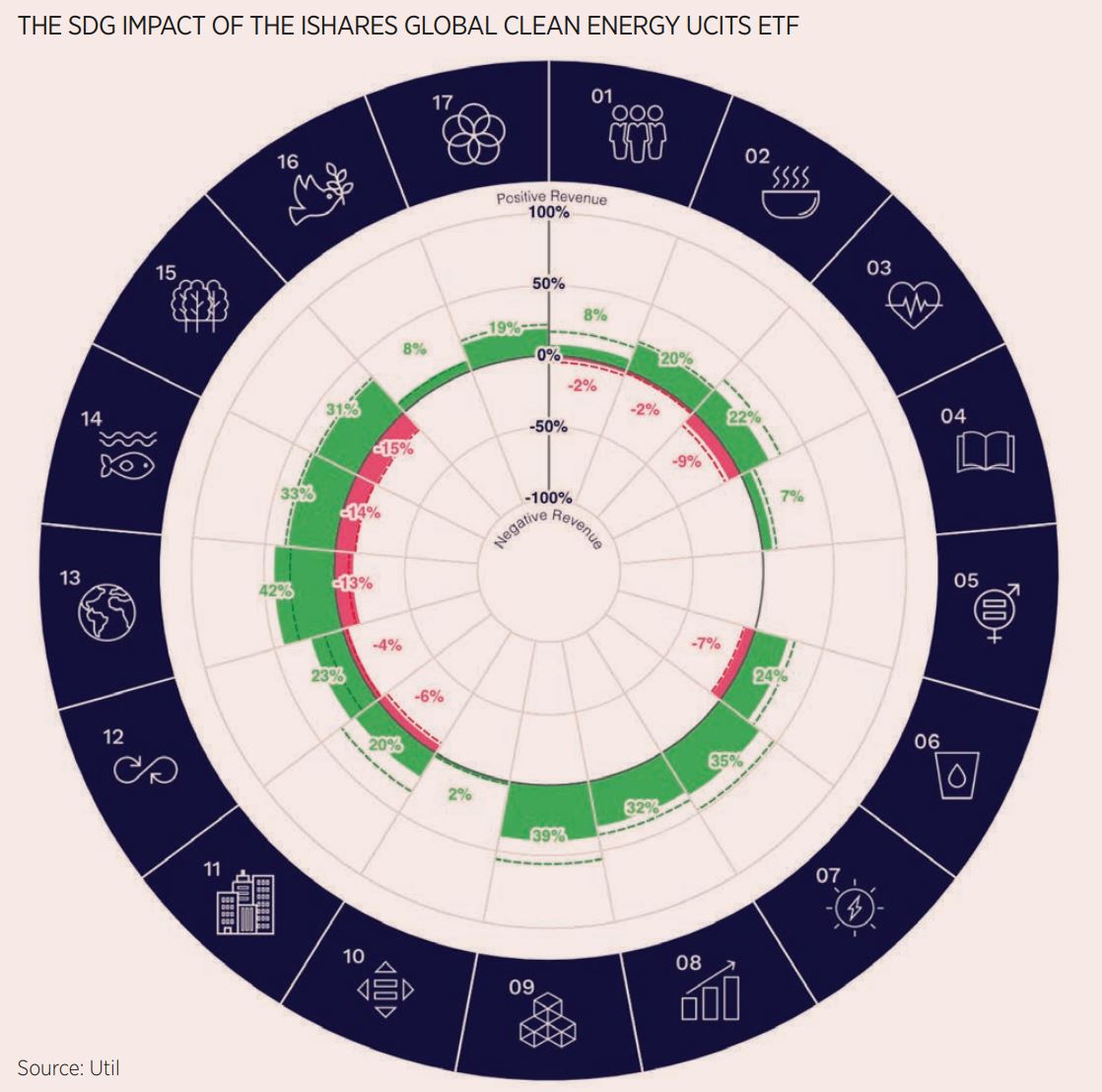

It is a scenario that could expose Article 9 – and the companies to which they funnel capital – to regulatory as well as volatility risk of the type that destabilised the iShares Global Clean Energy UCITS ETF (INRG) last year.

Previously, one of the biggest Article 9 funds that was recently downgraded to Article 8, INRG's top 10 holdings represent almost 50% of its total exposure today. Its impact may be best-in-class but are there enough undervalued best-in-class opportunities to meet demand?

Critics have been quick to blast Article 9 funds for their perceived inadequacy, but could the problem be the labels rather than the products? Is it realistic to shoehorn investment vehicles into highly marketable categories that do not, comfortably, exist?

Might it make more sense, at least for now, to access the full – often messy, rarely unimpeachable – value chain of sustainable themes, understand and communicate the trade-offs, and engage with companies to improve their impact over time?

This article first appeared in ETF Insider, ETF Stream's monthly ETF magazine for professional investors in Europe. To access the full issue, click here.

Related articles