Ethical investing is becoming mainstream.

According to Barclays, thanks largely to rich millennials inheriting their parents money, fund managers are rushing out all kinds of ethical funds. However ethical funds can differ quite starkly.

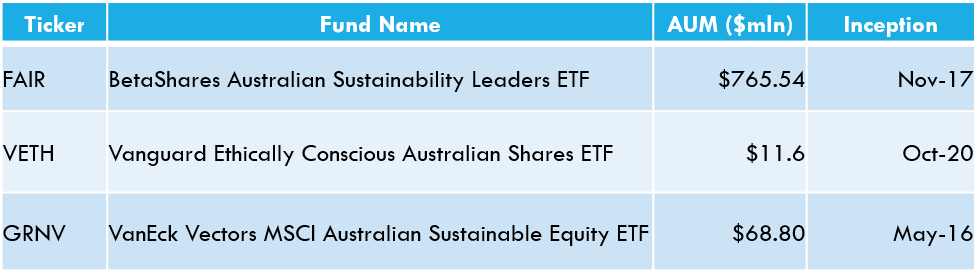

In Australia there are three main ethical Australian shares ETFs. Below we take a look.

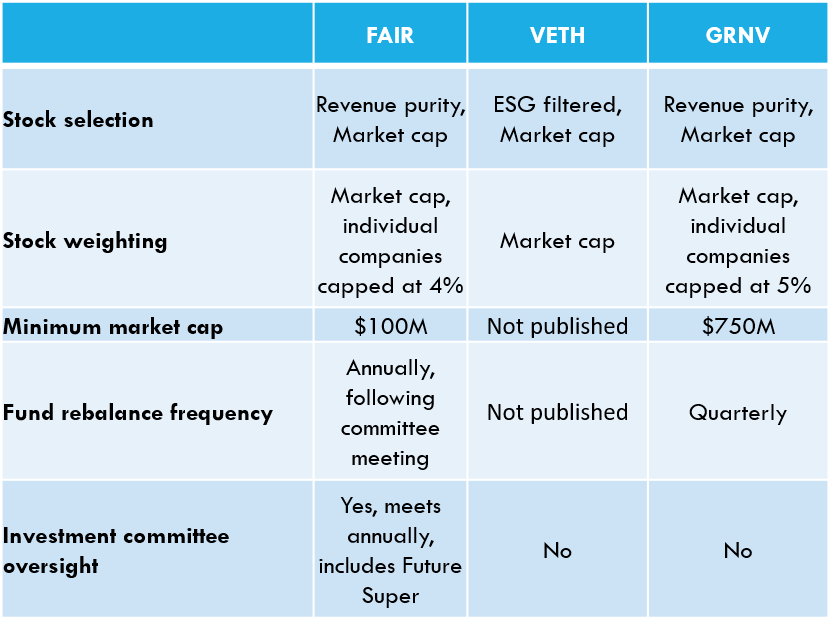

Investment strategies

BetaShares Australian Sustainability Leaders ETF (FAIR)

ETHI was the first ETF to take ethical investing seriously. FAIR is co-managed by Future Super, the superannuation fund founded by former Canberra Greens candidates Simon Sheik and Adam Verwey. Future Super has a seat on the investment committee, which quite can be quite activist.

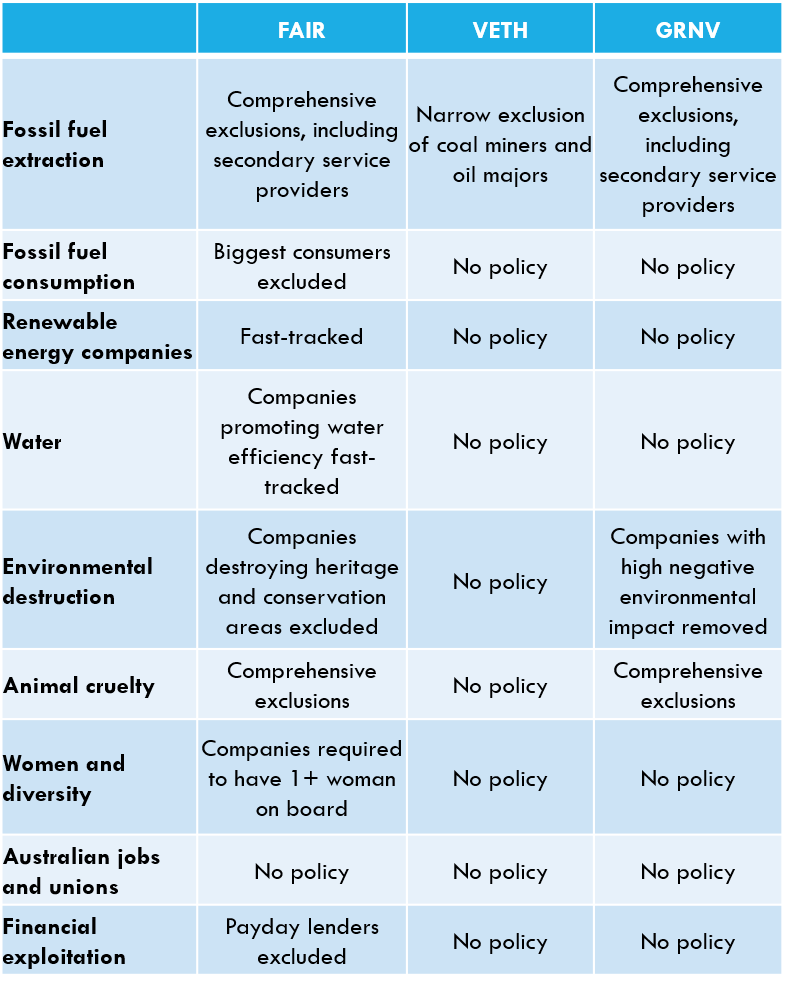

The fund makes far-reaching exclusions of companies involved in fossil fuel production and consumption. Renewable energy companies then get fast-tracked into the index. The big banks, almost all the miners, and a congeries of other businesses deemed unworthy by the committee are also removed.

FAIR allows small businesses into its index thanks to its $100 million minimum market capitalisation. This could, theoretically, result in capacity constraints if the fund hits mega-scale. Stock weights are capped at 4%, tilting the portfolio to smaller companies.

VanEck Vectors MSCI Australian Sustainable Equity ETF (GRNV)

GRNV is something of a halfway point between FAIR and VETH. First, it removes the fossil fuel companies and the cookie cutter corporate bad guys such as porn, tobacco, weapons and gambling businesses. Second, index provider MSCI scores companies on how good a corporate citizen they are. Scoring is based on box ticking surveys sent to businesses. Assessed criteria include impact on local communities, promoting good nutrition and health, supporting animal welfare—among others. The worst offenders are then removed from the index. Companies with market cap larger than $750M can qualify in the index. Stocks are capped at 5%, which creates a size tilt.

Vanguard Ethically Conscious Australian Shares ETF (VETH)

VETH has the narrowest ethical screen. It removes only companies directly involved in mining and oil, as well as the cookie cutter baddies of porn, gambling, etc. Because the fossil fuel removals reduce exposure to the energy sector, VETH tweaks the weights of stocks to bring sector diversification back in line with the ASX 300. This makes the fund, by design, closely follow the market. Because the banks and miners are mostly in the fund, franking and yield will be higher than the other two funds. Like other Vanguard ETFs, VETH lends the shares that it owns out to short sellers in order to make rental fees and boost the fund’s revenue.

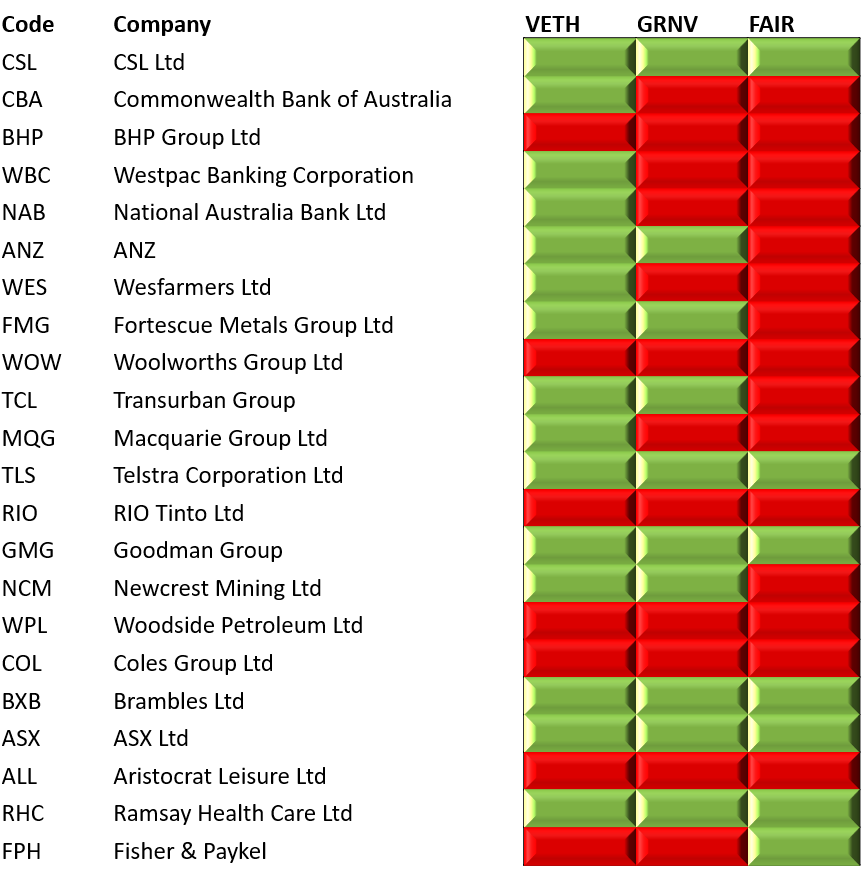

Politics and ethics: which companies get excluded?

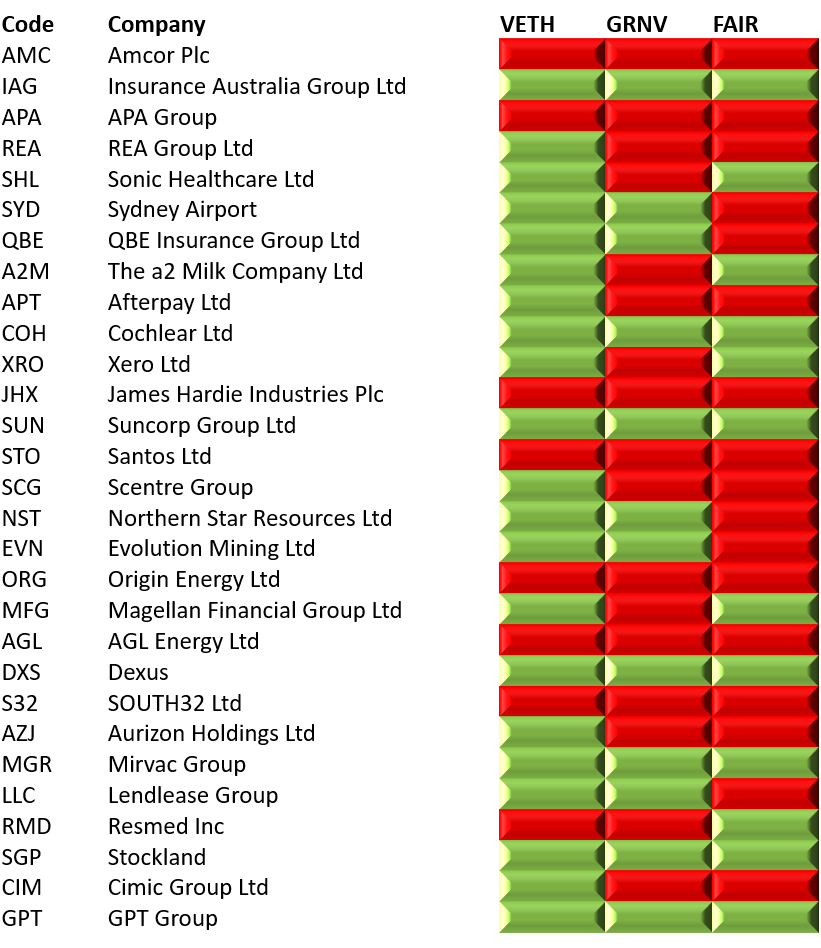

The ethical filtering of these three ETFs admits of a spectrum. VETH is the least extensive and FAIR is the most. GRNV is somewhere in the middle. The best way to see this is looking straight at the exclusions. Below is a table of biggest 50 companies on the ASX stocks. A red box indicates a company has been excluded, a green box that it is included.

As you can see, FAIR doesn’t let many ASX 50 companies in. This partly owes to the index criteria. But it also owes to the investment committee, which has quite a bit of power over what stocks get in the fund. This from the PDS:

“A company exposed to significant ESG-related reputational risk or controversy may also be excluded where the Responsible Investment Committee considers that its inclusion would be inconsistent with the values of the Index.”

The net result is that FAIR’s portfolio can - at times - seem bespoke. An example, for me, was how every miner and bank gets removed, spare two: Pilbera Minerals, the lithium miner, and Bendigo Bank. Why were these two companies spared the axe? Was it the index? Or the committee? It’s hard to tell.

GRNV for its part doesn’t include any Kiwi companies. So A2 Milk, Spark, Xero, Meridian Energy are all gone. Even though, one may have thought, that from an ESG perspective they’re on the light side of the force. I suspect this relates to how MSCI puts the initial stock universe of Australian companies together.

I found it interesting that GRNV excludes funds manager Magellan. Reading the index methodology closely I couldn’t understand the exclusion. Maybe MSCI regards high fee active managers as unethical.

VETH makes more run-of-the-mill exclusions. The only perhaps surprising exclusions are Coles and Woolworths – at least from the top 50 stocks. I think both of these relate to their extensive ownership of poker machines.

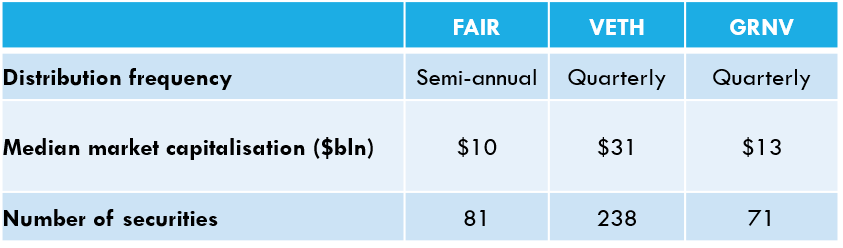

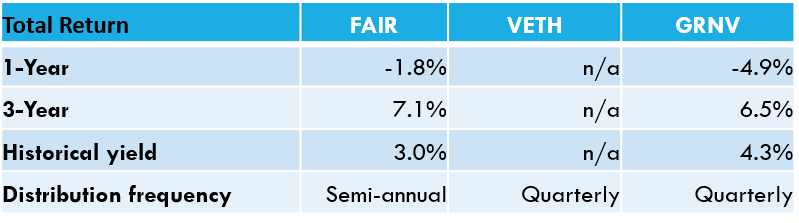

Performance

VETH is too new to have any real track record. This means performance comparisons have to be made between GRNV and FAIR.

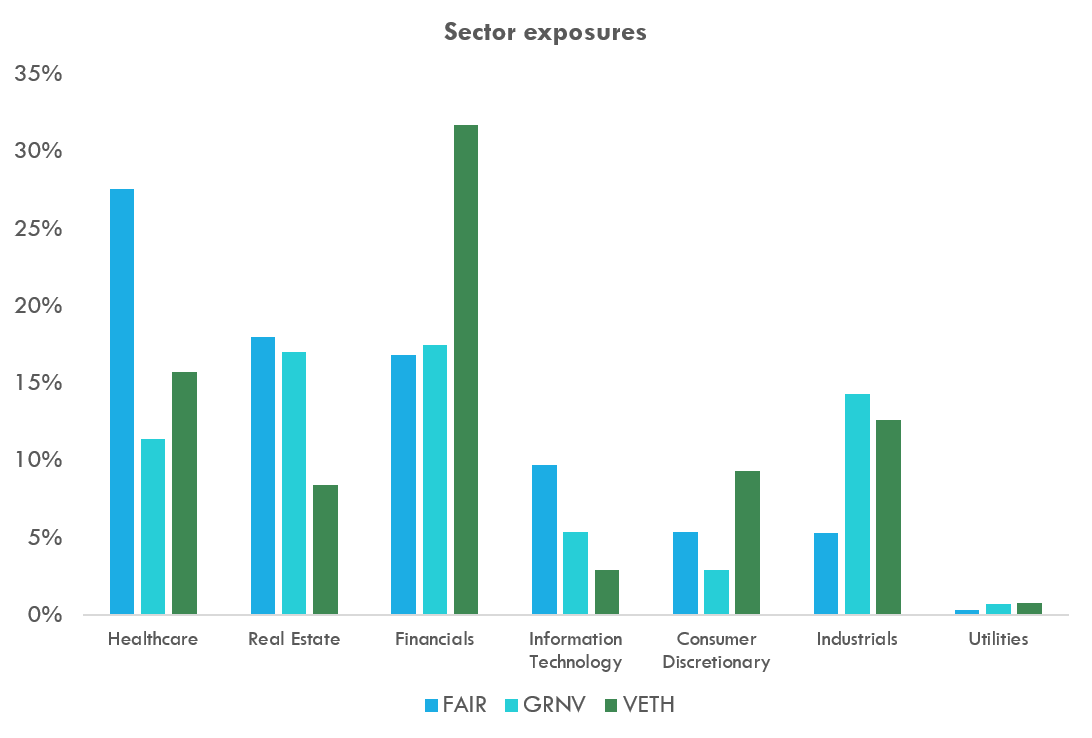

Here, FAIR has outperformed. A look at sector exposures gives some insight into why. FAIR has a big tilt towards technology and healthcare. These sector tilts – which are common among ESG ETFs – have powered the fund in a coronavirus riddled market.

Another reason for FAIR’s outperformance is its more extensive use of Kiwi stocks. Australians tend to be a bit oblivious to how much better performing Auckland’s share market has been than Sydney’s. The NZX 50 – New Zealand’s premier share market gauge – has crushed the ASX 200 on a total return basis the past 10 years. Making matters more pronounced, many top performing ASX 200 shares – such as Goodman Group, Xero, A2 – are all Kiwi businesses anyway.

Fees and trading costs

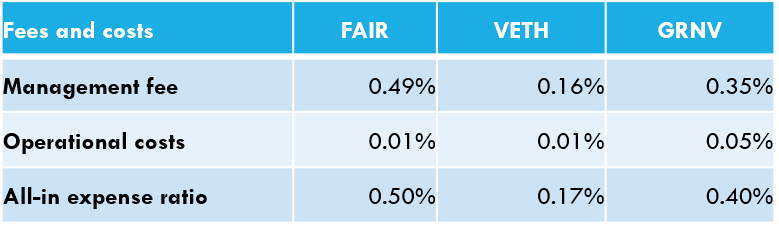

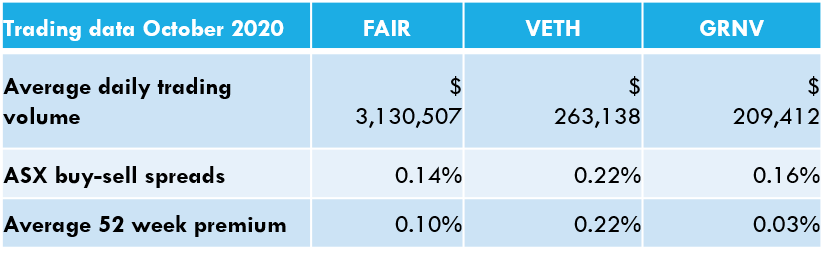

The fees of GRNV and FAIR are similar once every cost is considered. Aside from management fees, the important additional costs are transactional and operational costs. These are usually quite small and details of them get buried in the PDS.

VETH for its part has the lowest fees. This is unsurprising giving Vanguard’s incredible scale and not-for-profit structure.

The costs of trading these ETFs on the ASX – called “spreads” in finance jargon – are relatively similar. This is perhaps surprising. Conventional trading wisdom suggests that spreads fall the more an ETF gets traded. After all, the more something trades the cheaper and easier it is to match buyers and sellers.

So it is curious that FAIR, despite being far more heavily traded than its competitors, has spreads that are comparable. Why might this be? I suspect its to do with the smaller companies that FAIR includes in its portfolio. Looking at the bottom of the basket, there are tiny companies you’ve probably never heard of. (Bubs Australia or Superloop, anyone?) When companies cost more to buy and sell, those higher costs to ETF investors as wider spreads.

Going forward however I’d expect VETH to have the tightest spreads. This is because – to simplify and cut a long story short – market makers can piggyback off VETH’s big brother VAS. The two correlate closely.

Conclusion

VETH has the advantage of low costs and a securities lending programme, which helps juice up yield. It also tightly tracks the market, ensuring it won’t underperform. However, its ethical screening is less ambitious, which may leave more committed ethical investors unfulfilled. That being said, the fund is very appropriate for investors who just want to cheaply dump oil, gas and coal.

GRNV is a bit of a halfway house. It has more far-reaching exclusions than VETH, but not as broad as FAIR. The fund is double the price of VETH, but cheaper than FAIR. It may be appropriate for investors looking for a middle-ground between VETH and FAIR.

FAIR is a bit of an active-passive hybrid, thanks to its investment committee. At 0.50% a year it is also expensive. That said, its ethical screen is comprehensive and ambitious. In my reading – and judging by AUM, the market’s reading as well – its portfolio most closely resembles what ethically-minded Australian investors will want.

This article is paired with Australia's best ethical global shares ETF