The idea of funnelling money into the best corporate actors is simple enough to understand, however, the real challenges come with deciding what ESG best practice looks like and which of tens of thousands of listed companies (and sovereigns) meet these criteria.

Such questions have surfaced again in recent debates over plans by the EU to include nuclear energy and natural gas in its taxonomy for sustainable industries. Last year, nuclear power was set to be included in a complementary Delegated Act of the taxonomy but in October, the ‘Nuclear Alliance’ of 15 ministers from countries including France, Finland and the Czech Republic pushed for it to be included in the main taxonomy by the end of 2021.

Opposing this in recent weeks, Germany offered support for the temporary use of natural gas but publicly objected to nuclear being included in the taxonomy, while Austria threatened to take legal action should nuclear be included following the end of the consultation process.

Such conflicts are hardly surprising, for a number of reasons. When one thinks of how to define ethical investing and the scope of building blocks it encompasses, this is a highly values-based and subjective undertaking. Also, given that international standards-setters rely on input from political actors with distinct interests, the odds of complete consensus are slim at best.

Adrian Whelan, head of market intelligence at Brown Brothers Harriman (BBH), said: “The ambition of the EU taxonomy, the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) and the Corporate Sustainable Reporting Directive (CSRD) is to have a very prescriptive rule set that is all-encompassing and sets the benchmark for others to follow.

“The intention was to have something scientific, with a lot of data points to allow very little wiggle room resulting in these binary activities which are good or bad.”

Unfortunately, Whelan added, this effort to create a scientific way of filtering capital has encountered a stalemate between conflicting interests.

“This objective measuring system mindset does not sit well in the real world, because the realpolitik is that the impact of the taxonomy on specific countries and industries can be disproportionate. That is what drove the inclusion of gas and nuclear; some countries said they cannot upkeep their current economic model by adhering to these rules,” he explained.

ESG at its core not only asks participants to make the moral, tangible, but its subtext demands they situate this within a nexus of pre-existing priorities. At best, this creates a grey area of actors with differing views on how to reach an ostensibly similar end goal.

Green data leviathan

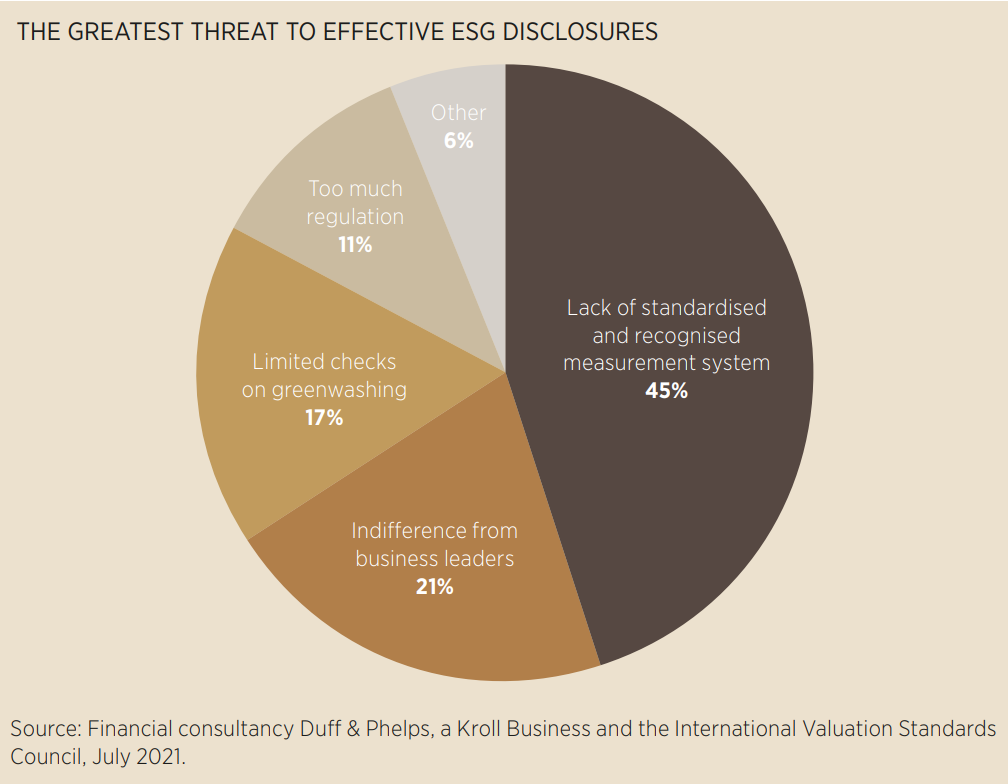

While there may not be any exact consensus on what ESG is, the baseline for effectively separating ‘better’ and ‘worse’ securities is reliable data.

Naturally, not having a common understanding of what falls within the remit of ESG is a hindrance, as companies and data providers spread out resources to keep in step with the latest batch of regulation.

At present, investors have to navigate the plethora of national and regional, political and non-political frameworks ranging from the EU, UK post-Brexit and upcoming US agendas, to other voluntary standards including the Taskforce For Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) and many more.

As with politics, accounting or any other cross-border venture, the lack of a unilateral ESG architecture can be attributed to the absence of a single, international authority on the issue. Whelan said the closest example is the European Commission and its trialogue process. However, this then suffers from member state fragmentation of rules because of local conventions, particularly on directives.

He added that even if another global standard were launched, such as the incoming International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) from the IFRS Foundation, it would not “wash away” the body of existing standards and would face the same data-gathering challenges as the incumbents.

For starters, a lack of mandatory data reporting means hopes of complete ESG data are distant from the get-go. Looking at emissions data, for instance, the TCFD said only a third of companies reported their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions following its recommendation to use the GHG protocol in 2018. Likewise, by the end of 2021, only around half of current emissions data are reported directly by companies, according to Vitali Kalesnik, director of research for Europe, at Research Affiliates.

While self-reporting bias is an issue, Kalesnik said reported data is 2.4 times more effective than the alternative – estimated data based on data provider proxies – given the latter tend to be based on crude models that fail to identify the greener companies within ‘brown’ sectors.

Aside from a lack of willingness to report on ESG metrics, BBH’s Whelan says the ESG data industry remains in its relative infancy, with a genuine scarcity of data on the “eye-watering” number of metrics companies might be expected to report on.

One part of this scarcity comes from differing capabilities, with the larger, listed companies more able to spend on analysts to gather ESG data and therefore more likely to be favoured in the ESG benchmarks that rely on such data.

“We already see a style bias. These rules play to the advantage of large issuers because of their scale and resources to aggregate this kind of data,” Whelan argued. “Smaller entities such as SMEs are busy building their businesses, and they are being told to undergo this big administrative task they need to do to get climate data, gender data and more for investors.”

He added that similar biases exist in data reporting favouring public over private and developed over emerging markets, with the risk of these areas with less-developed ESG reporting infrastructure being defunded.

Arguably, however, the devil is in the details with ESG data gathering. Even with standardised ESG definitions and mandatory disclosure, the battle for reliable ESG will be decided in how companies and data gatherers portray performance on metrics at the granular end of the spectrum.

Supporting this, a paper from Fidelity Climate Solutions found as much as 90% of overall emissions may be accounted for within Scope 3 of the GHG protocol. This data point is not only yet to be considered as a norm within most ESG frameworks but will require insights into the minutiae of often opaque supply chains.

This will mean standardised collection methodology, cooperation by companies and no small measure of patience.

ESG’s long road to maturity

While challenges seem innumerable, the sheer amount of attention and new developments mean ESG regulation and product issuance is being refined at an impressive rate.

For instance, the European Commission added to its work on the SFDR and CSDR in late 2021 by furthering plans for the Electronic Single Access Point (ESAP) to be added to its Capital Markets Union (CMU) package.

The ESAP is expected to be similar to the EDGAR system in the US, and from 2024, the plan is for it to be a free-to-access central portal of corporate data – including on sustainability. This will then feed into ESMA with the goal of creating a machine-readable and standardised database for users to access.

Outside of Europe, Whelan predicted the US will implement a more pragmatic and benign model of ESG – that is more sympathetic to the significant role of petrochemical companies in the US economy – which could become a “global bellwether”. He also foresees “a lot of fast followers” in Asian markets, with both Hong Kong and China looking toward the EU standards; however, once again, he warned complete harmonisation is not possible because of societal differences.

Taking a broad view, Whelan said the years following today’s “ESG policy bubble” will be followed by a period of consolidation, with perhaps five to eight global and regional standards proving to be the most detailed, flexible and practically usable. This will come with investors, regulators and product providers compromising on what level of disclosure and data is valuable, Whelan added.

He concluded: “What you should see are fewer proprietary screening processes and more of these global champion screening systems. All the data providers would lose some of their proprietary expertise and value proposition, but they at least have consistent answers – and that is the problem at the moment.”

There will not be a one-size-fits-all version of ESG. The next step is to decide what range of ESG can be accommodated and to gain as full a data picture as possible. These ends will be achieved over the course of years, not months.

This article first appeared in ETF Insider, ETF Stream's monthly ETF magazine for professional investors in Europe. To access the full issue, click here.

Related articles