Many investors desire to make a strong impact on climate change. Today, however, because mandatory carbon emissions reporting does not exist on a global scale, the only data available to them is a combination of voluntarily reported data and data estimated by data providers.

As my co-authors and I show in Green Data vs Greenwashing: Do Corporate Carbon Emissions Data Enable Investors to Mitigate Climate Change? estimated data are inadequate substitutes for reported data. We find that estimated emissions data are 2.4 times less effective than reported data in identifying the worst carbon emitters.

Based on our findings, we are now advocating for international mandatory and audited carbon emissions disclosure using a standard reporting protocol as the most effective means to alleviate the inaccuracies in estimated carbon emissions data. In the meantime, investors should use their influence to encourage companies to voluntarily report their emissions.

Moving in the right direction

Fortunately, change appears to be on the horizon in the European Union, the region leading the world in initiating climate-change regulation.

On 21 April 2021, the European Commission published the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). The CSRD extends the scope of the 2014 Non-financial Reporting Directive, which currently applies in the EU, to propose mandatory reporting according to EU sustainability standards as well as mandatory audits of reported information.

The proposed reporting requirements apply to all large EU companies and all companies listed on EU-regulated exchanges. The proposal is a major step forward in improving the accuracy of sustainability-related data.

Unfortunately, many countries lack comparable regulation. Until similar regulation is adopted in other nations, investors will be constrained by imperfect GHG emissions data in their goals of meaningfully mitigating global climate change.

The power of accurate data

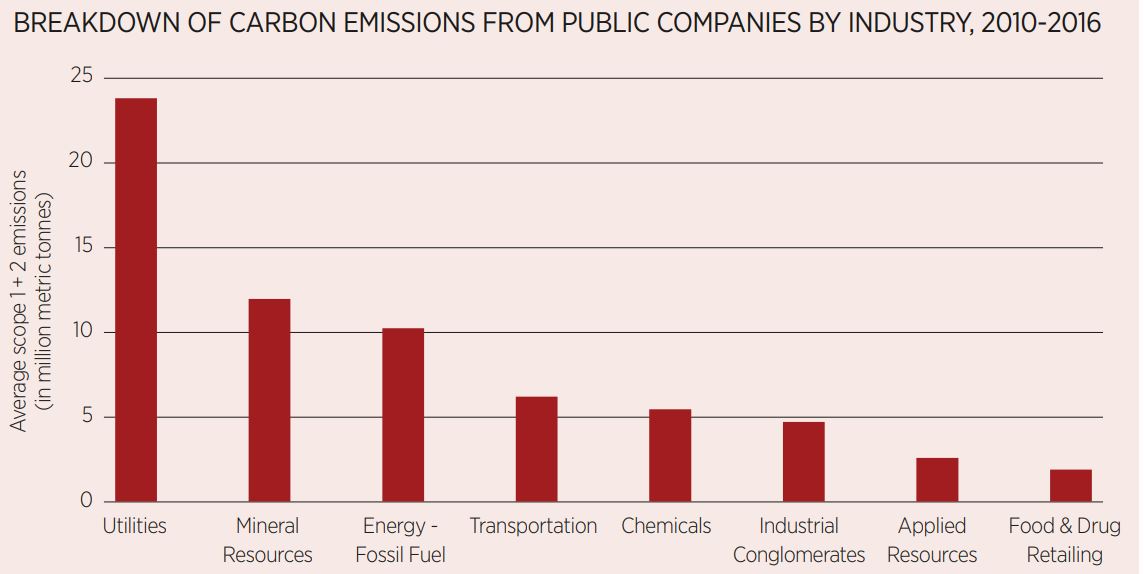

Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are highly concentrated: 71% of GHG emissions since 1988 are linked to just 100 active fossil fuel producers, according to the global environmental-reporting non-profit CDP.

Therefore, if investors were to have accurate data, their ability to positively impact climate change could be substantial. In contrast, only 5% of the entire universe of carbon emitters is responsible for 80% of total emissions. With accurate emissions data, investor actions can obviously have a meaningful impact, but without accuracy can quickly lose efficacy.

Investors can follow two routes in their portfolio selection decisions: 1) shift capital from brown to green companies or 2) invest in brown companies and exert pressure on corporate management to adopt greener policies. With both policies, however, investors require accurate data. In the absence of mandatory reporting, that needed accuracy is compromised. The data providers are not at fault, they are doing the best they can with the information available to them.

Beware of garbage-in/garbage-out

The saying garbage-in/garbage-out (GIGO) aptly pertains to carbon emissions data. To guard against GIGO, we believe five characteristics should apply to GHG emissions-related data.

The data should be widely available, comparable between companies, consistent across data providers and accurately reflect true emissions. Lastly, forward-looking information, such as emission reduction targets, should have predictive power. These five criteria are not being attained under the current voluntary reporting framework.

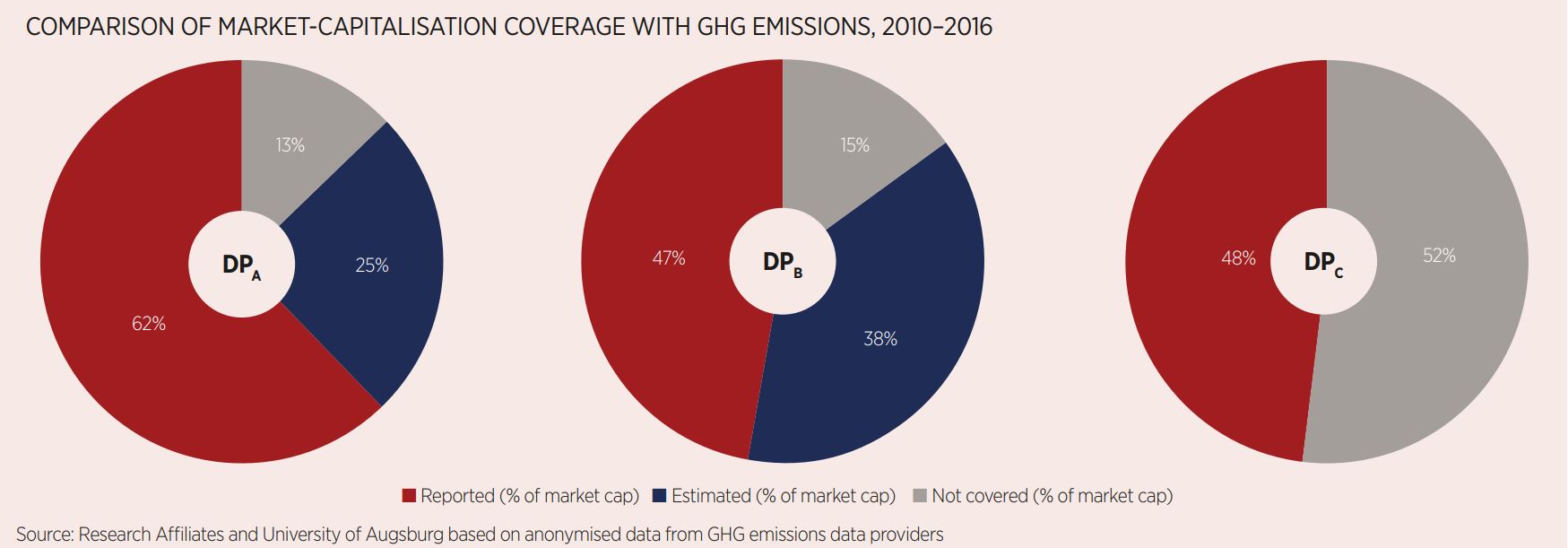

We analysed data from three major carbon data providers (anonymously labelled as DPA, DPB, and DPC) for the seven-year period 2010-2016.

Their reported carbon emissions data ranged from 47% to 62% of emitting companies based on market-capitalisation coverage. They provide roughly the same percentage in carbon emissions coverage by metric gigatons. In both coverage areas, a large gap in reported data must be estimated by the data providers.

Today, no universally accepted reporting standard for GHG emissions exists. The GHG protocol is the commonly followed standard but a number of nations have issued their own reporting guidelines, muddying the waters of data comparability.

According to the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), in 2018 only one-third of companies reported their GHG emissions following the TCFD’s recommendation to use the GHG protocol. Without a universal reporting standard, data comparability is not achievable. To estimate the missing data of nonreporting companies, data providers turn to proprietary estimation models.

Data providers typically position their proprietary estimation models as being quite sophisticated, leading many investors to view the estimated data they produce as similar in quality to reported emissions data.

The reality is that the estimates are a noisy proxy of true emissions. They generally rely on broad business metrics and industry affiliations, and often very simple financial information, such as net sales or number of employees.

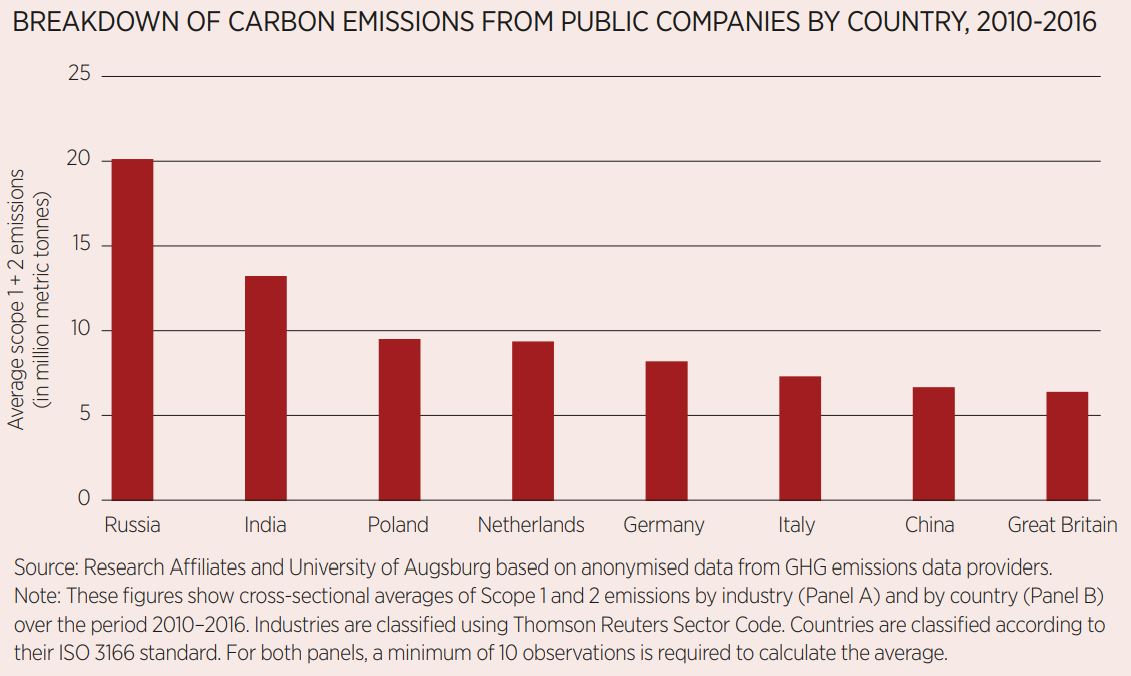

We find that simple correlates, such as industry and size effects, explain the bulk of the variation in the estimated data.

Therefore, a simple model using a company’s net sales, industry affiliation, country of domicile, and year as fixed variables is just as accurate as the data estimated by the data providers in our analysis. Failing to capture information beyond simple correlates makes it much more difficult for investors to identify the green companies in brown sectors and can lead to counterproductive investor actions in mitigating climate change.

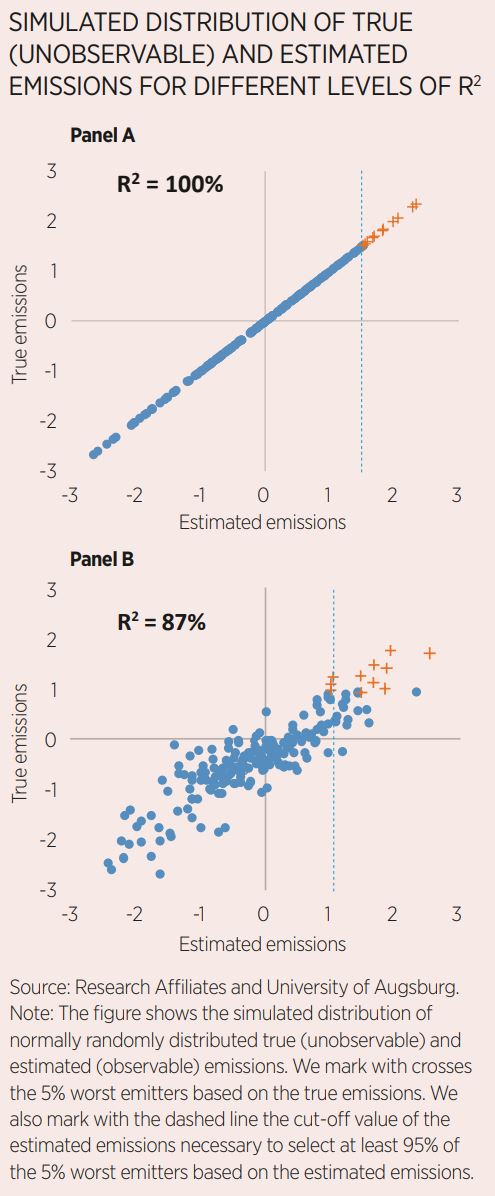

At the present time, estimated data fail the criterion of reflecting true emissions. We tested the effects of using estimated data to identify the 5% worst emitters in a universe of 10,000 companies. With perfect data (reported or estimated with an R2 of 100%) an investor would know exactly the 500 worst emitters. With imperfect data, an investor must exclude more companies from their portfolio to safely remove the 500 worst emitters.

Our paper provides the full details of our approach. In short, when estimating the accuracy of estimated data, we find that by using estimated data the number of stocks excluded from a portfolio is 2.4 times larger (1,190) relative to the 500.

Therefore, the effectiveness of the investor’s desired action to mitigate climate change is reduced by 2.4 times, which we call the inefficiency of using estimated emissions.

Forward-looking data shortcomings

Data providers also evaluate a set of forward-looking data, which are theoretically just as important as the data on current emissions. Forward-looking information can help investors identify those companies driving the transition to a green economy and which may perhaps benefit from the decarbonisation trend.

Conversely, they can inform investors about which companies are not planning to reduce emissions, and perhaps are even planning to increase them. Importantly, these data should have the forecasting ability for future changes in emissions.

Our empirical examination of forward-looking emissions estimates found no evidence these data offer any useful forecasting insights. The lack of predictability is likely driven by the use of nonscientifically verified estimation methods.

Also, much of the data used to derive these estimates may just be “cheap talk” from companies engaged in greenwashing. We argue that forward-looking information should be externally verified before investors rely on it.

A call for disclosure

Investors play a major role in combatting climate change and they need high-quality GHG data to be effective. Only about half (47%-62%) of current emissions data are reported directly by companies.

These data are the highest quality available but still have several drawbacks: reporting is voluntary, the reporting standard used is at the discretion of the reporting company and reported data are inconsistent across reporting companies. The first two concerns contribute to potential self-reporting bias. Our research finds that forward-looking information has no predictive power in explaining future changes in emissions.

Our research results also demonstrate that estimated GHG data, although capturing most of the emissions variation, is inefficient in helping investors identify the worst emitters. Investor actions are diluted at least 2.4 times when they rely on estimated versus reported emissions data. The result is inadequacy in investors’ ability to identify the green companies in brown sectors.

We conclude that the implicit assumption that estimated data help investors make accurate assessments about which companies are green, and therefore worthy of their green investing dollars, is a misconception.

In summary, without mandatory reporting and standardised reporting practices, GHG data are inadequate to accurately guide green investment toward a positive environmental impact.

The green sheen that many companies burnish themselves with is only possible in a world absent mandatory reporting. The glare of green sheen should be substantially dulled if mandatory carbon emissions disclosure were adopted.

Vitali Kalesnik is partner and director of research for Europe at Research Affiliates

This article first appeared in ETF Insider, ETF Stream's new monthly ETF magazine for professional investors in Europe. To access the full issue, click here.

Related articles