Beginning in the early 1980s a whole professional class of consultants grew to offer assistance to a rapidly growing pool of institutional investment funds, largely in what are now labeled as old-fashioned pensions, which provided a defined stream of benefits to retirees. One of the tasks undertaken by the consultants was to measure performance and to recommend replacing managers if the performance was disappointing. As the data began to accumulate late in that decade, major doubts arose about whether the investment managers were adding value. This created a new pressure on manager selection. Managers were challenged to at least cover their own fees. Sometimes they did, but often they did not.

During the 1990s, in what was one of the most powerful, long-lasting bull markets in recent history, the generalized performance pressure seemed to ease, and the role of the consultants gradually morphed into suggesting more targeted, specialized investment approaches or "styles." Managers, for example, were required to choose whether to invest in large cap stocks or small cap stocks, but generally not both. Similarly, were they going to be growth managers or value managers? Consultants kept close track and watched carefully for any "style drift."

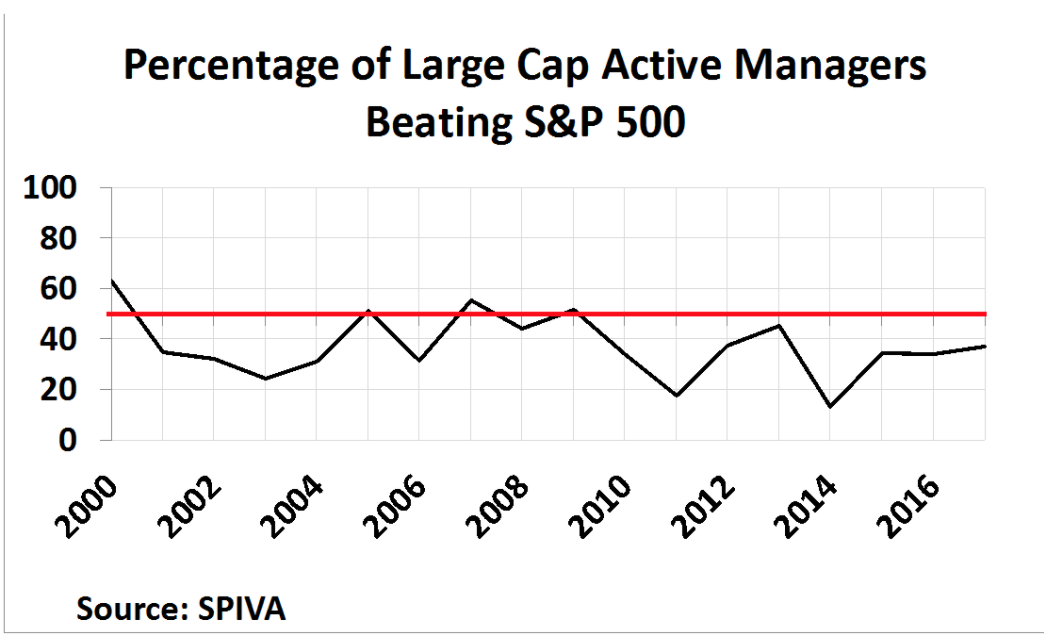

After the year 2000, the data started to accumulate to show that no matter which "style box" a manager was in, as a group, managers failed to beat their relevant benchmarks.

The chart shows a representative sample gathered by Standard & Poor's in their "SPIVA" data (S&P Index vs. Active).

From the early days of this performance pressure, it was increasingly clear that portfolio managers' fees were a big reason for underperformance. As well, the research needed to create the portfolios was increasingly expensive. The pressures on managers grew.

Competing Returns and a Breakthrough

Even before these performance shortcomings came under increasingly intense scrutiny, "index investing" became of greater interest. A portfolio could easily be constructed which exactly replicated the index. This passive approach came with extremely low management fees. "Indexing" was partly premised on a growing body of academic interest in the early and mid-1970s as well as from veteran investors who sensed (or learned the hard way) just how difficult and expensive it was to "beat the market." Given the rapid overall growth of assets, indexing initially only accounted for a very small portion of the total. However, there were other, newer, pressures on the traditional managers as well.

Before 1999, investor—particularly investment strategists—each had their own opinion about which sector and industry a company might belong in. It was a particularly fluid set of definitions. When energy stocks got hot, for example, some strategists included the railroads as energy stocks because they hauled coal and had some rights of way that included potential energy production. Companies in the higher tech aerospace business sometimes were classified as industrials and sometimes as technology.

The lack of a standard classification for each company slowed the growing attempts by outside consultants to attribute performance to sector weightings and selection. That all changed in 1999 when Standard & Poor's and Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI) joined forces to classify each company worldwide into one of ten sectors and about 100 industries. What turned the project into the standard was that the classifications were accompanied by more than ten years of historical data. This Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS®) set the stage for the historic takeoff of growth in the ETF world. Strategists stopped dreaming up classifications and, instead, went to work employing the products that grew in the wake of the project.

Targeting Returns

Both before and especially after 1999, ETFs began to be created to reflect different segments of the overall market. ETFs for small, mid cap, international, industry, country and more began to be offered. Investment strategists who typically had a macro and "top down" perspective were big supporters of this slicing and dicing of the whole traded market. Some of those pre-1999 strategists who were forced to create their own sectors and segments were faced with the additional frustration of not having any specialized security to use for implementing their strategy.

While there were several "sector" mutual funds, like a fund specializing in retailers, or a fund specializing in technology stocks, strategists were not guaranteed to receive just a generic retail return or a generic technology return. Rather, for good or bad, the returns were highly dependent on the success of the individuals managing those funds. As strategists dipped into the pool of

industry mutual funds, they never really knew what would come back in performance; but the new ETFs were designed from the start to be just passive reflections of their sector or segment. No person would intervene in the process.

The first major ETF-like products to employ GICS were State Street Bank's Sector SPDRs ("Spiders"). A version of these products had been offered in 1998, but they were soon revised to reflect the new GICS scheme. Competing ETFs rapidly followed. Investors who became bearish, as an example, could now quickly sell all their technology "exposure" and buy just utilities, hoping to perform relatively better if general concerns turned bearish. All it took was two ticker symbols. Inevitably, assets were taken from traditional, "active" managers.

Still Another Way to Slice the Market

The "fundamental" company research being conducted by traditional portfolio managers was not completely scorned. After all, would it not be nice to own stocks that were relatively inexpensive compared to their earnings? In a passive index fund, the securities are owned in the same percentages they represent in the index. Virtually every index at that time (whether for the market or a segment) was merely an index of the total market value of all the member stocks. That is, the portion of a portfolio any individual stock represented was its relative market value weight. However, analysts and some academics contended that the index contained a range of stocks, from overvalued to undervalued. What if instead of weighting each stock by its market capitalization, the weights were proportional to the amount of earnings a company had to the total earnings in the index? In theory, stocks that were cheap had lots more earnings per market value dollar than those which were expensive. So, a scheme that weighted earnings would result in a tilt of the portfolio toward theoretically more attractively valued stocks. Early in the decade of the 2000s, the first of these kinds of ETFs were introduced.

In what turns out to be a brilliant marketing stroke, these ETFs were called "smart beta." "Dumb beta" was seen by some as just the prior group of capitalization weighted index ETFs. Others joined in and weighted their portfolios by the dividends in the index. Others by the revenues. In the 15 years since, smart beta ETFs have grown to almost $700 billion in assets just in the US. Interest in these funds has grown apace internationally.

A 1952 Concept Still Called "Modern"

The notion of "beta" is at least a half century old. "Modern Portfolio Theory" (MPT) was heralded by Harry Markowitz in 1952, promoting the notion that a portfolio could absorb the disparate individual volatilities of the member stocks. About a decade later, William Sharpe introduced the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM), suggesting the market will proportionately reward risks (defined then as a stock's beta). In academia it became accepted that investors were rational—so much so, that the market was "efficient" (Efficient Market Hypothesis - EMH) and no special reward could be actively earned by investors beyond the risks they took.

Over the last several decades, while still somehow giving EMH its due, academics introduced so-called "anomalies" into the literature. The first of these was the idea that cheap stocks could earn

a premium and then, a second, was that smaller capitalization stocks could as well. By now, however, the EMH hypothesis is getting a little stretched, as more than several dozen anomalies have been posited. Virtually every one of these "factors" has had a place among traditional, active portfolio managers. Perhaps a little sheepishly, academia has started to label its highly mathematically-oriented discourse as "Standard Finance" rather than MPT. But how "efficient" and "rational" is a market with dozens of so-called "anomalies?"

"Smart" Not Smart? "Active" Not Active?

A portfolio weighted by, say, earnings, cannot long stay as different as it was initially to a portfolio weighted by market capitalization. As more money goes into a winning smart beta ETF, the undervalued stocks will tend to gradually become much less undervalued as they receive a disproportionate amount of new funds. From this, it follows that a fundamentally-weighted scheme cannot always outperform the market cap index. One answer to the problem is that if the smart beta ETF were "rebalanced" frequently, then the drift mentioned here would be mitigated. However, this presupposes that the value (or other) anomaly is rewarded before the rebalancing. Unfortunately, most academic studies suggest that, in fact, it typically takes somewhere between three and five years for anomalies to be rewarded. Meantime, there is a good probability that during periods shorter than that there could be noticeable underperformance. Therefore, the results obtained seem unduly influenced by the timing of the purchase and sale of the smart beta ETF. In other words, it is the investor who needs to be smart in these cases, because even a smart beta fund is just another passive (dumb?) fund. Smart beta ETFs, in a sense, were perhaps smart on the day they were conceived but, thereafter, discretion passed to the outside investor or advisor.

On December 24, 2015, a CNBC host said that actively managed funds have "stock pickers" at the helm. But perhaps recognizing the challenges mentioned above and the desire to be different, ETF issuers have recently begun to hint that what they are offering is really an active fund, which is a relatively new definition of active.

However, this activity seems to be at least somewhat mechanical. In one case, the rebalancing is just done more frequently and thus there is more activity in the portfolio. In another approach, a manager or a computer program watches to make sure the factors stay within prescribed limits and makes trades to rebalance them back into line, instead of waiting for the calendar to tell them when to rebalance, as is the case for other ETFs, both smart and dumb.

The very newest wrinkle is to employ artificial intelligence and "deep learning" (neural networks) to find and implement factors. Again, humans are clearly involved in the research and rulemaking, but that may be the only place for exercising discretion. Investors in these new concepts should probably be aware that in the general debate between man and machine, the estimates run from now to thirty years from now when the machines can successfully do the kind of activities contemplated here.

It's Our Fault

The fundamental challenge is that the markets are not rational. Why? Humans are not rational, not even generally or partly or usefully. Even those humans involved in building the AI networks are subject to all kinds of behavioral biases. The chances that there could be antiseptic for behavior are very low.

Even the choice to invest in any fund—smart, dumb, intelligent, or active—is obviously an action. In the end, it is clear that discipline is needed by someone. Obviously the better that discipline is supported by logic and evidence, the higher the odds for success. It is only adroit marketing that can make it seem as if there were some other, easy way to invest.