Where trends lead, products follow, and private credit has been an unstoppable investment trend in recent years.

Private credit – where non-bank entities lend directly to borrowers – took off after the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) when banks reined in their risk appetite, creating a lacuna in lending markets.

The illiquidity of these investments does not make ETFs a natural home, but that has not stopped issuers seeking a slice of the private credit pie.

Last week, State Street Global Advisors (SSGA) filed plans in the US to launch an ETF that invests in both public and private credit. The SEC is mulling it over, but could the likes ever hit the European continent?

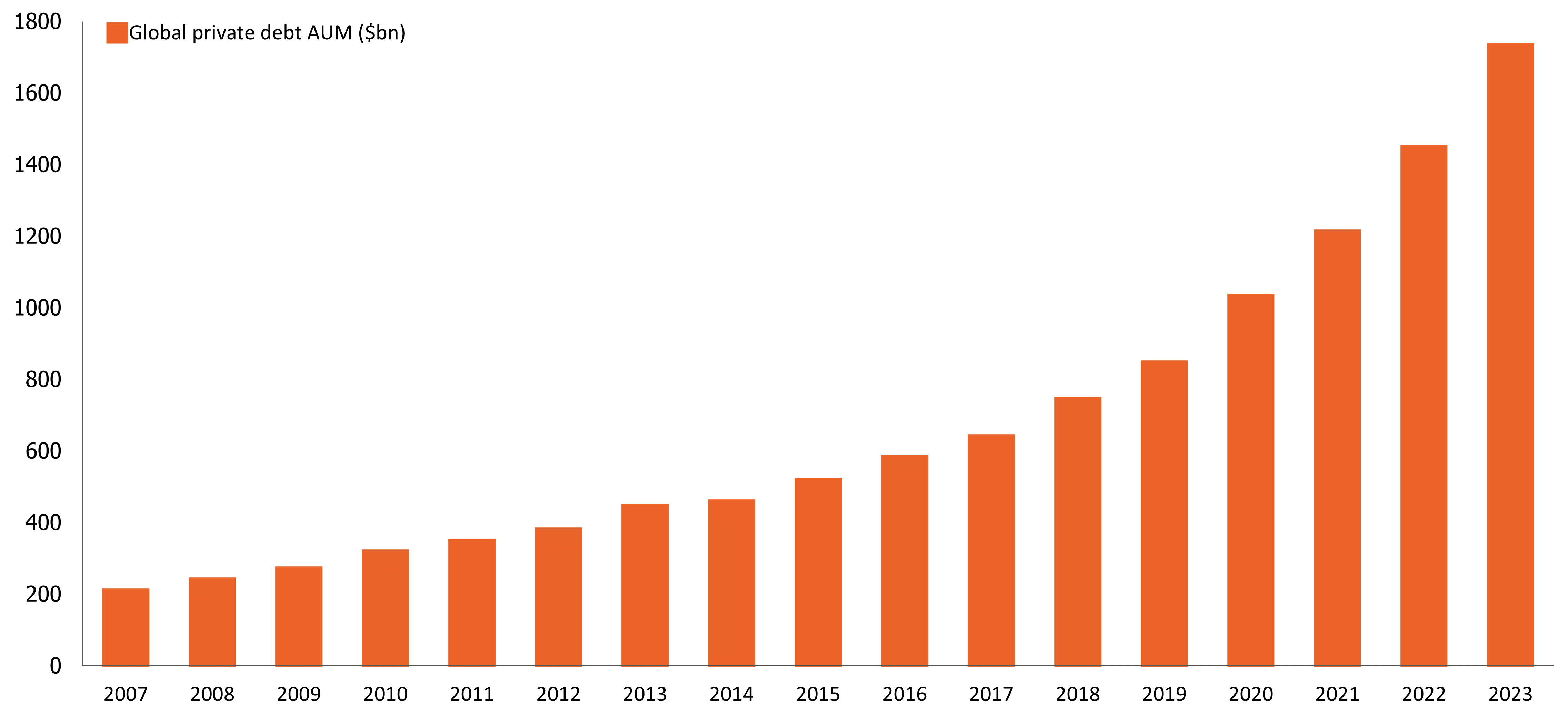

Chart 1: Private Credit AUM has exploded since the GFC

Source: Preqin

Private credit assets swelled to $1.7trn by the end of 2023, up from around $200bn in 2007, according to Preqin data, as private equity firms and alternative asset managers stepped into the post-GFC void.

For investors, private credit offers diversification benefits thanks to low correlations with public equities and bonds and private debt instruments have historically delivered lower loss rates than public alternatives, according to Morgan Stanley research.

Returns, too, can be superior as private credit captures an illiquidity premium – a spread over public corporate bonds – compensation for the non-tradeable nature of the debt.

How would the ETF work?

SSGA has partnered with Apollo Global Management on the new product – the SPDR SSGA Apollo IG Public & Private Credit ETF – and Apollo will source all the debt instruments held in the fund, at least 80% of which must be investment grade.

Some of the holdings will be private credit instruments. As defined by the proposal, this includes direct lending to private companies in private offerings, as well as asset-backed securities such as commercial real estate, residential mortgage loans and consumer finance instruments.

The filing does not specify a limit or target level of private credit exposure.

SEC rules currently prohibit open-ended vehicles like ETFs holding more than 15% of their assets in illiquid investments, but Apollo’s contractual obligations as liquidity provider may allow it to circumvent this ceiling.

According to the agreement, Apollo will provide ‘executable quotations’ on all private credit instruments and purchase them from the fund, up to a ‘daily limit’, at or above the quoted price. The size of the daily limit is undefined.

What are the key risks?

With prices determined by Apollo, not supply and demand on a regulated exchange, there is no true arbitrage mechanism at work, while a lot hinges on Apollo’s ability to offer quotations, particularly in moments of stress.

The filing acknowledges that ‘if Apollo is unable to meet its obligations to provide firm bids…assets that were deemed liquid…may become illiquid’.

A further risk is that redemptions exceed Apollo’s daily limit forcing the sale of the fund’s more liquid holdings to meet them.

This makes the ETF vulnerable to a run dynamic.

In other words, if jitters emerge about Apollo’s financial health, investors may look to get out before bids get pulled.

Furthermore, if the resolve of other investors in the fund comes into question, allocators may seek to exit before the daily limit is exceeded and public assets are liquidated at distressed prices. The opacity around such limit will not help to calm the nerves.

How will the regulators view it?

Whether or not the SEC green-lights the proposal will give some flavour of regulatory appetite for these products.

In Europe, it will depend “on whether the loans in question meet the UCITS definition of transferable securities or money market instruments (MMIs)”, Sergey Dolomanov, partner at William Fry told ETF Stream.

“Transferable securities are mainly shares, bonds and units in other funds. I do not believe loans could qualify under this definition.”

The “UCITS definition of an MMI includes instruments with regular yield adjustments which potentially makes it possible to invest in floating rate unsecuritised loans [like direct private loans],” according to Dolomanov.

However, to be considered an MMI, the instrument must be “liquid, ‘freely transferable’ and capable of being accurately valued”, added Dolomanov, something such loans appear at odds with.

European regulators are therefore unlikely to be acquiescent.

Indeed, Dolomanov highlighted that the Luxembourg regulator, the CSSF, has previously “announced that it does not consider loans to be eligible assets”.

And while the Central Bank of Ireland (CBI) has made no such pronouncement, “there is no doubt that the CBI is aware of the CSSF position and equally conscious of the European Securities and Markets Authority’s call for evidence in relation to UCITS eligible assets.”

Jose Garcia-Zarate, associate director of manager research at Morningstar, had “serious doubts” an arrangement similar to SSGA and Apollo’s would be acceptable in Europe.

“The arrangement places Apollo, a private entity, as the sole source of liquidity and transferability for an inherently illiquid market, something that can generate all sorts of red flags for the regulator and potential investors,” he said.

Are there alternatives?

There are a handful of ways issuers could construct a private credit UCITS ETF, though none would offer as clean exposure as the product SSGA and Apollo are proposing in the US.

Manooj Mistry, chief operating officer at HANetf, said an issuer could theoretically “simulate the performance of a private credit portfolio… [by] creating a proxy basket of UCITS eligible transferable securities that are highly correlated with the private credit market”.

This could be done by investing directly “in a portfolio of credit-linked notes (CLNs) or other listed instruments deemed transferable securities”. In the case of CLNs, “this would require at least 20 different note issuances to ensure sufficient diversification”.

It could also be achieved via a swap. But the challenge here would be to find “a willing counterparty to provide the swap exposure”, Mistry added.

An ETC/ETP could be an alternative to a UCITS ETF wrapper, but again providing a willing counterparty might prove challenging.

“Another option would be to create an Alternative Investment Fund (AIF) ETF wrapper,” Mistry said. “AIFs have more flexible investment guidelines versus UCITS and are typically marketed to institutional investors. But regulators may have concerns about creating an exchange-traded version that is then accessible by retail investors.”

Will issuers push ahead?

Even if private credit securities were deemed UCITS-eligible MMIs, if issued by an unlisted corporation, a UCITS may not invest more than 10% of its assets in such loans, Dolomanov added.

SSGA did not mention the proposed weighting level for its US ETF, and did not respond to a request for comment.

Given the tall regulatory hurdles to clear in Europe issuers may well decide that pursuing a private credit ETF is not worth the cost.

Indeed, there are question marks over what level of demand such a product would attract in the first place.

Kamil Sudiyarov, ETF product manager at VanEck Europe, said “ETF market participation and infrastructure development rates remain far below that of the US”.

“That makes launching such niche products a less attractive proposition with tougher trading conditions and a lower likelihood of success,” he added.

Conclusion

An ETF structured similarly to SSGA’s US proposal would require creative interpretation of the UCITS eligibility criteria, or a change in the regulations altogether – unlikely in the near-term.

The ETF industry, however, has become known for imaginative solutions to investor problems.

“If investors are looking to access intraday exposure to private credit then I am sure a product will emerge,” Mistry said.