Smart beta ETFs have gone from flavour of the month to flavour of the year. What was once an obscure buzzword known only to finance wonks has reached retail investors in a remarkably short space of time.

Yet experts - and many investors - remain unconvinced that they actually work. Among the unconvinced is Bill Sharpe, the Nobel laureate who coined the term beta, who said smart beta ETFs make him "sick".

And his views appear a consensus among scholars. Expressing what appears a majority opinion, Princeton Professor and best-selling author Burton Malkiel said:

"smart beta portfolios… are more a testament to smart marketing rather than smart investing… actual records of smart beta portfolios that run with real money do not in general replicate the results suggested by academic studies."

But there remains an anomaly in smart beta ETFs: equal weight.

Equal-weighted ETFs take a market-weighted index like the S&P 500. But rather than giving the biggest companies - be it Apple or whatever else - the biggest slice of cake, they give every company an equal share.

The approach is an anomaly because, on the one hand, it looks just like something a smart beta ETF would do: using an interesting idea (size tilt) to build an index. (For this reason, they are usually classed as a smart beta product). Yet, on the other hand, it seems nothing like smart beta. After all, equal weighted ETFs use the same market-weighted indexes everyone knows and loves, but places an equal bet on every horse. It's more a tweak than an innovation.

But there's another reason to separate equal-weighted funds from smart beta litter box: they might actually work.

Academics like equal weighting

While academics have mostly frowned on smart beta funds - be they dividend, quality, momentum, value - they have mostly smiled on equally weighted ones.

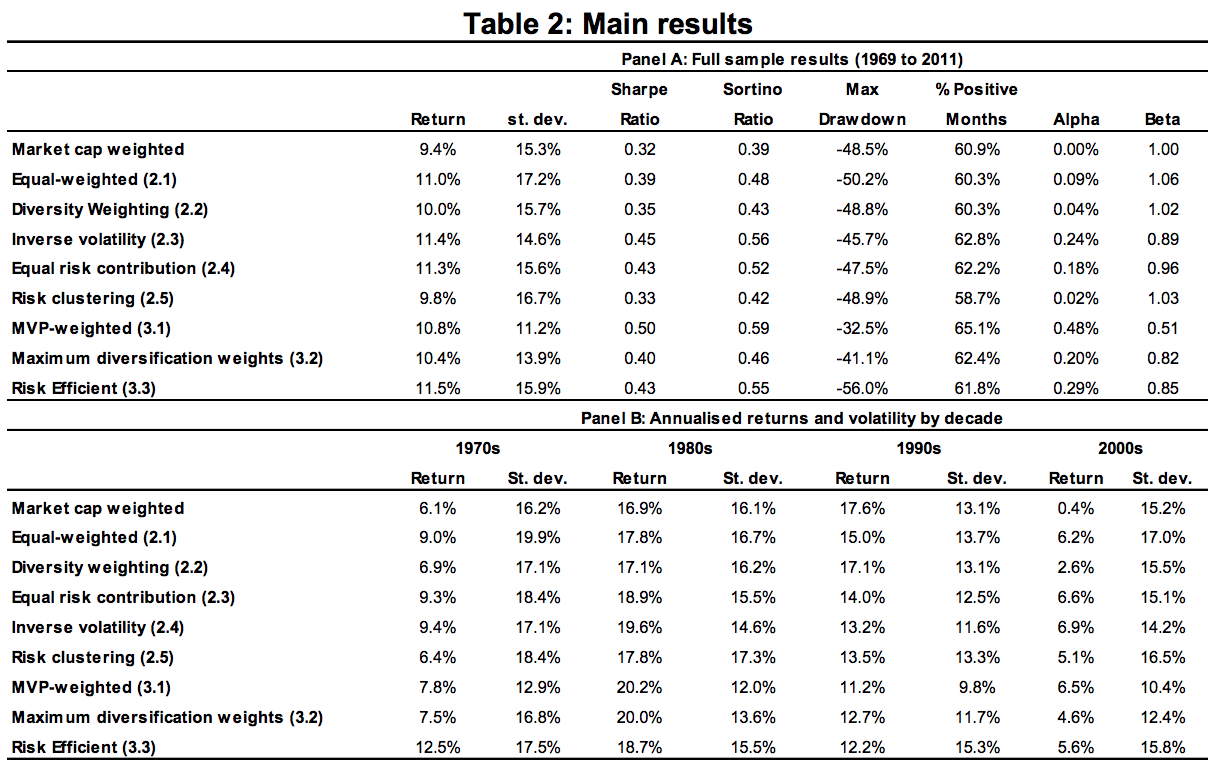

The latest study on the topic, published in January 2018, comes from Solactive, a German index provider. The study, entitled 'When size doesn't matter', compared the performance of market weighted portfolios with equally weighted ones and tried to figure out what differences occur and why.

It found that equally weighted beat market cap weighted funds from 2000 to 2017, falling more during bear markets, but recovering faster after downturns. "The results confirm that equal weight outperforms market cap weight, both in the United States and Europe," Solactive wrote.

The report suggested that equal weight does better because it is more exposed to smaller companies. And smaller companies tend to be better value of the long term (this is sometimes referred to as the "size factor" by quants). But equally weighted funds also have an in-built buy low sell high feature, Solactive noted.

When equally weighted funds are rebalanced, companies whose stock prices have risen have to be sold off, so that their weight can be reduced and equality maintained. (If a company's stock price increases its weighting also increases). Companies whose stocks have declined, by contrast, are bought into more heavily, in order to bring their weight back up. This dynamic means that any equally weighted fund is always buying cheap and selling dear.

Solactive aren't the only ones to study this or to find that equally weighted funds tend to do better. Researchers at Cass Business School in London, led by Professor Andrew Clare, demonstrated this to dramatic effect using a bunch of "monkey" portfolios.

The monkey portfolios picked stocks randomly, weighting each stock at 0.1%. There was no limit on how many times the monkey could pick the one stock. The performance of the monkey portfolios was compared to the performance of the market and equally weighted US stock index. The process was repeated 10 million times, ensuring the data set was large enough.

Shockingly, the study found that "nearly every monkey beats the performance of the market [weighted] index." Yet very few monkeys managed to beat the equally weighted one.

But there are weaknesses

Equally weighted funds also have weaknesses. And here, it's important to draw a distinction between an equally weighted index and an equally weighted fund. This distinction is crucial because a fund has to deal with real-world costs and problems, like turnover. An index, by contrast, can work in the abstract.

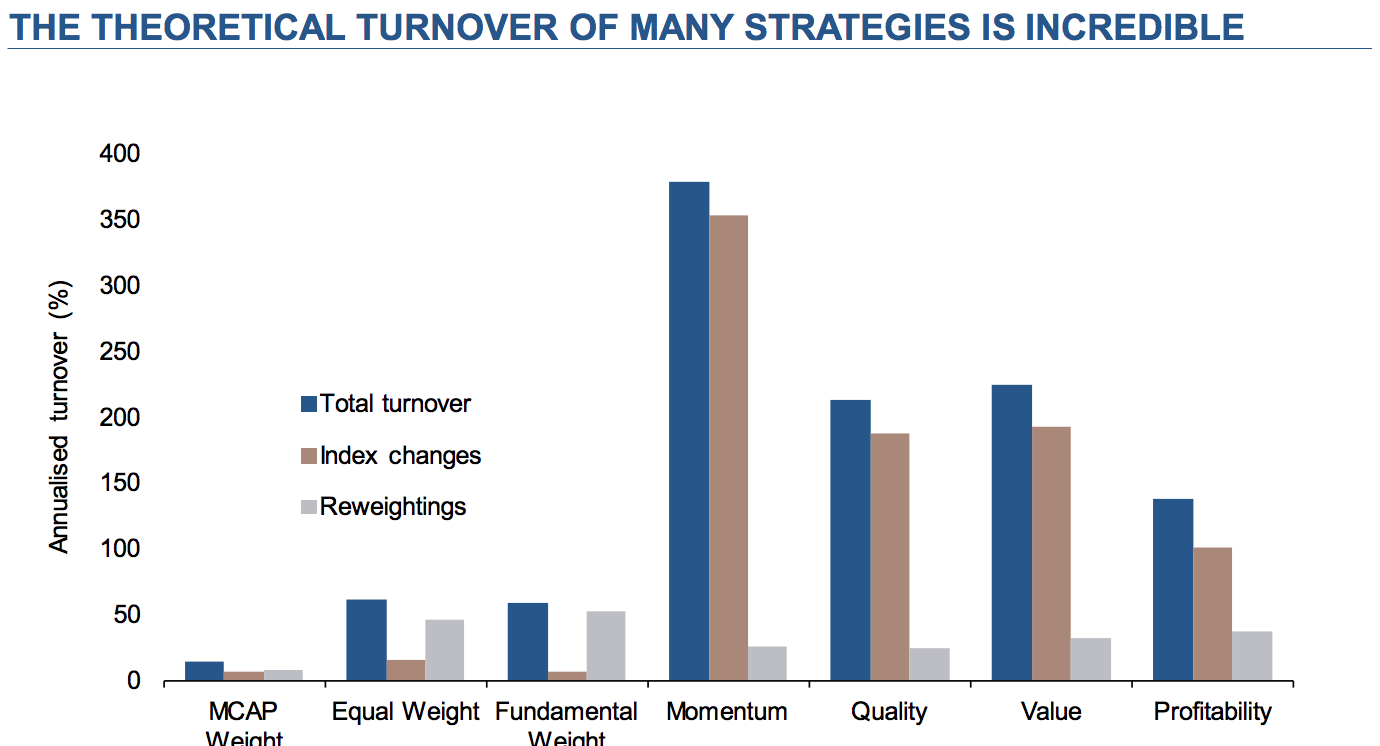

One of the major weaknesses of any equally weighted fund is that they incur much higher turnover costs than market weighted ones. The Solactive study cited above warned that these costs can "reduce (if not entirely negate) any excess returns".

This point has also been made by Andre Lapthorne, an analyst at SocGen and one of Europe's leading quants. Lapthorne warns that equal-weighted funds' turnover costs can be four times higher than their market weighted counterparts. This undermines performance because the costs of buying and selling shares get passed on to the ETF's owner (as lower performance).

Higher cost is another weakness of equally weighted funds, although this is improving. Equally weighted ETFs typically cost double their market weighted equivalents. In the US, the biggest S&P 500 tracker, SPY, costs around 9 basis points. The biggest equally weighted S&P 500 ETF, Guggenheim's RSP, costs 20 bps (Lowered recently from 40 bps, in a sign of improving cost). Again, this has obvious implication for performance.

[caption id="attachment_2840" align="alignnone" width="1024"] Source: Andrew Lapthorne[/caption]

The rising tide

Globally, equally weighted ETFs are few in number. But their popularity is growing. There were very few equal-weighted ETFs outside the US prior to 2010. But now they have a global footprint. They're also colonising other indexes, including property, sectors and factors.

Yet equal weight products have struggled to be profitable. Some equally weighted funds have been successful. Guggenheim's RSP has more than $15bn under management, making it one of the world's most profitable ETFs. In Australia, the VanEck Vectors Aus Equal Weight ETF (MVW) has raked in US$334m, making it one of Australia's larger equity ETFs. Yet almost every other equally weighted ETF worldwide has had a hard time hitting the $10m mark. In order to break even, ETFs typically need $50m at the very least.

Why is this? Likely because the education work simply hasn't been done. Very few investors know that equally weighted ETFs exist, meaning that issuers often have a lot of legwork to do. Other investors know they exist, but don't know the arguments in favour of them. But if this educational legwork can be done, there's good reason to think equally weighted ETFs can succeed - for issuers and investors alike.