Many investors have been re-assessing the opportunity within fixed income given the new macro environment. A challenging 2022 for the asset class saw the key benchmark of the Bloomberg Global Aggregate Total Return index falling over 20%, its greatest drawdown since its inception over 30 years ago.

As a result, what was a notable story over the last decade – the sheer volume of negative-yielding debt in the world – has finally reached zero in early 2023 after exceeding $18trn in late 2020.

Yields, especially on a nominal basis, are now at more attractive levels than what investors have recently been accustomed to. Time will tell but the time to be truly excited about fixed income may have already passed some investors by.

For example, UK 10-year yields are below pre-Liz Truss premiership levels and are indeed closer to 3% (from their peak at c.4.5% in late 2022).

Opportunity in fixed income certainly exists in 2023 but we maintain our view that taking a nuanced approach to the asset class is preferable – a stance vindicated in 2022 by poor performance of broad bond indices which often have too much duration risk.

We also like to be able to have more control over other key risks such as currency and credit which are less easily controlled in broad indices.

Chart 1: 10-year government bond yields below their recent high

Source: ETFbook

ETF landscape

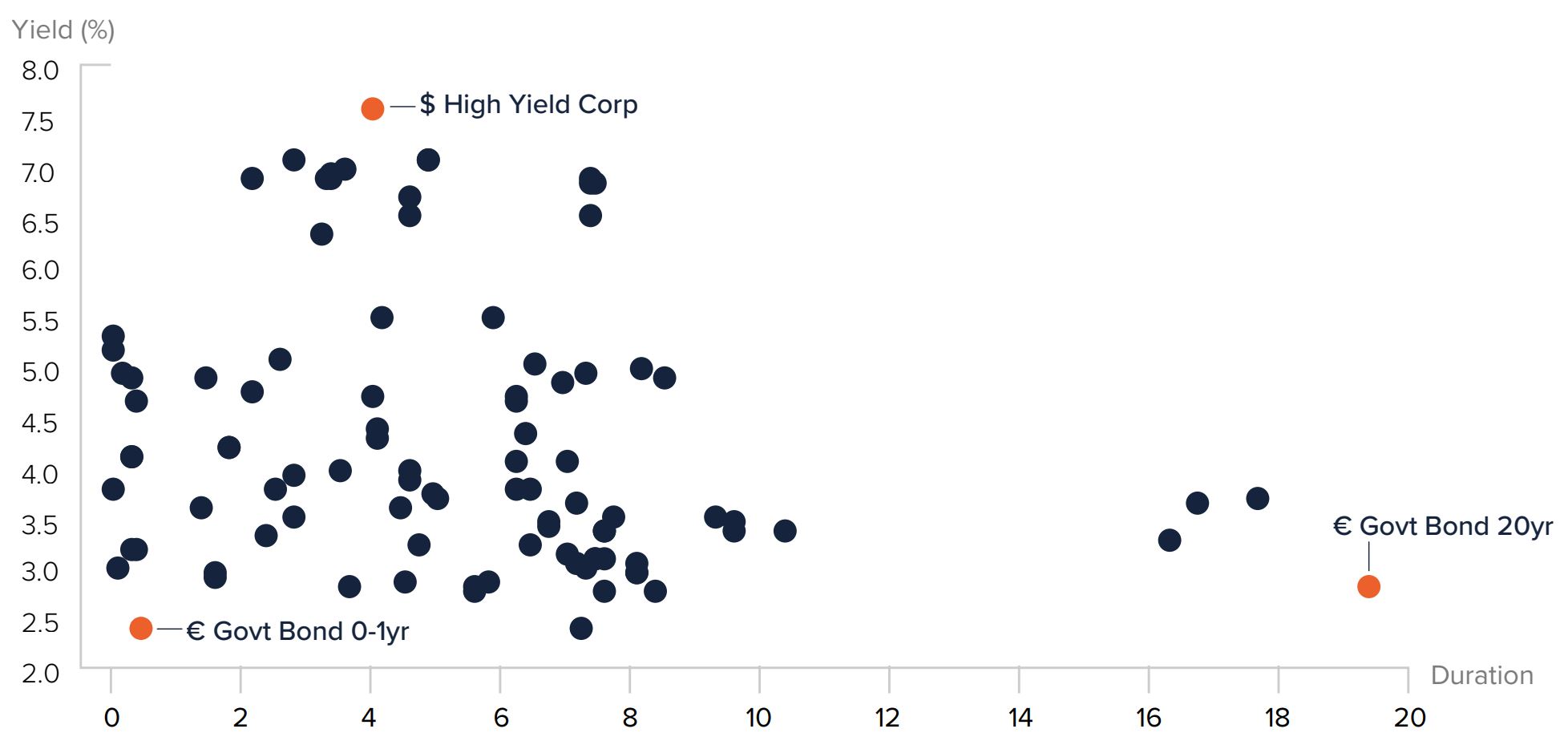

The UCITS ETF universe offers investors a broad selection, with the scatter chart capturing over half of the universe by AUM – each dot represents a separate ETF.

Two points can be inferred from this chart (i) bond yields are now at more reasonable levels; and (ii) yields curves are relatively flat and so a pick-up in yields may be best achieved by taking more credit (or currency) risk.

According to data from ETFbook, investment grade corporate credit has dominated flows (double that of government bonds) over the last seven months as investors try to capture some of the credit risk while inflation-linked bonds have now seen nine consecutive months of outflows.

The additional attention on fixed income ETFs, initially brought about by the market dislocation in March 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic and the dismal (and perhaps surprising) performance for 2022, is perversely welcome. As either a strategic or tactical investment, a key benefit of fixed income ETFs is the ease with which they allow investors access to underlying bond markets and their inherent diversification of single issuer risk.

While the traditionally fragmented and opaque market structure of fixed income instruments is at first thought not an obvious fit for ETFs, this could not be further from the truth.

In terms of portfolio management, fixed income ETFs are far more dynamic in their management of bond positions than the passive label may suggest. Passive ETFs can, for example, hold fewer or even more bonds than the underlying index and can participate in new issuances while active ETFs have even more flexibility.

Customised or more niche bond indices are widely used giving investors even more choice while the use of stratified sampling and in specie creations and redemptions allow for the efficient management of portfolios.

Chart 2: Fixed income ETFs by yield and duration

Source: ETFbook

Looking ahead in 2023

All eyes remain on inflation and on how central banks respond with the Federal Reserve, European Central Bank and Bank of England raising rates again in early February while suggesting that peak rates may be near. Markets have so far chosen to interpret recent news as dovish but are perhaps choosing to ignore some of the risks to this view.

After decades of negative bond versus equity correlation, rising correlations are important to consider. Traditionally negative correlation – one of the key benefits of bonds in portfolios – was absent in 2022 with traditional 60/40 portfolios receiving much criticism. This view (and the depiction of rising correlation) is often over-simplified.

The notion that central banks are more likely to care about persistent (and meaningfully above target) inflation than falling equity prices does carry weight (and it is indeed their mandate) but it is far from a complete and enduring guide to portfolio construction.

Indeed, for the first time since the late 2000s, major central banks now have room to turn dovish, which should not be discounted. For the most part, central banks have so far managed an orderly start to reduction of their balance sheets with the Fed’s already decreasing from approximately $9trn to $8.5trn.

The investment outlook for fixed income is as varied as the asset class itself and encapsulating the full ETF universe and its possible uses in client portfolios is challenging but there are a number of interesting areas to watch:

Ultra-short and short-duration bonds: With the rise in post-pandemic deposits, banks have been slow to pass on rate hikes to customers making the case for ultra-short bonds even more attractive (although not without risk, as seen in the March 2020 sell-off). Short-duration bonds were attractive in 2022 as they provided a place to shelter from rising rates and in 2023 they remain attractive with the relatively flat, and in cases inverted, yield curve. After months of coordinated central bank policy rate hikes, diverging policy decisions (and more importantly market expectations of them) over the rest of 2023 are bound to provide further risk and opportunity.

Investment grade credit: Economies have remained resilient with companies continuing to show their versatility in the face of higher (and increasing) rates. Unemployment levels near record lows and a recent easing of financial conditions (to the presumed displeasure of central banks) remain supportive of credit. While the greatly predicted global recession of 2023 may never arrive, the full impact of higher rates on the consumer and corporate earnings remains to be felt. The greater protection of investment grade over high yield may be attractive to investors but the trade-off is difficult to make.

Asia: From low-yielding Japanese government bonds to high yielding debt exposed to China real estate, the asset class is Asia is more varied than one might expect.

Emerging Market (EM) and Asia USD-denominated bonds are currently offering some of the highest yields in USD – JP Morgan’s EMBI index suffered its worst fall since 1998. With ETF index construction varying significantly, investors are spoilt for choice with a different way to obtain higher bond yields on US dollar-denominated bonds.

JP Morgan’s inclusion of Indian (local currency) bonds in its flagship index stalled in 2022 with investor concerns about market infrastructure and taxation but the opening up of India’s bond markets could lead to strong inflows (potentially $20bn- $30bn) which would benefit early investors in the existing bond ETFs.

While many investors were too late to the trade of China’s local currency bonds in 2022, the investment case over the medium- to long-term may be strong (depending on one’s view on China). ETF and index innovation provide excellent choice to investors.

Andrew Limberis is investment director at Omba Advisory & Investments

This article was first published inFixed Income Unlocked: After The Storm, an ETF Stream report