Index turnover arbitrage costs ETF owners 12 - 36 basis points a year, Solactive finds. But, thankfully, there are easy fixes.

Index turnover is one of the lesser known costs of owning an ETF. Proud of how cheap their products are, ETF issuers often advertise their management fees. Stockbrokers may not be proud of their bills, but at least they'll send you a receipt. Spreads you can see on screen.

But index turnover costs are invisible, because they're deducted from a fund's performance. There's no receipt, no dollar sign, no giveaway.

What are turnover costs? They occur when indexes change. Say a company has a few bad years and is no longer big enough to qualify in the S&P 500, so it gets replaced. This means that every fund tracking the S&P 500 has to sell the old company and buy the one replacing it. This buying and selling costs money, which investors - not the ETF provider - end up paying for.

Why does this cost money? A big part of the reason turnover costs so much is because of the arbitrageurs that lie in wait.

As it happens, traders can smell the breeze. They can forecast how an index will change. Anticipating these changes they can (and do) sell off the stocks getting dumped in advance and buy the ones getting added. This means that by the time index funds get around to changing the guard, the prices of the stocks being added and subtracted have been scrambled.

These arbitrageurs are a part of the reason that turnover costs what it does. But how much exactly does it cost?

How much does arbitrage cost?

A new research paper by Solactive, a German index provider, called "The hidden index turnover costs" tries to calculate exactly this. And, crucially, studies how best to deal with it.

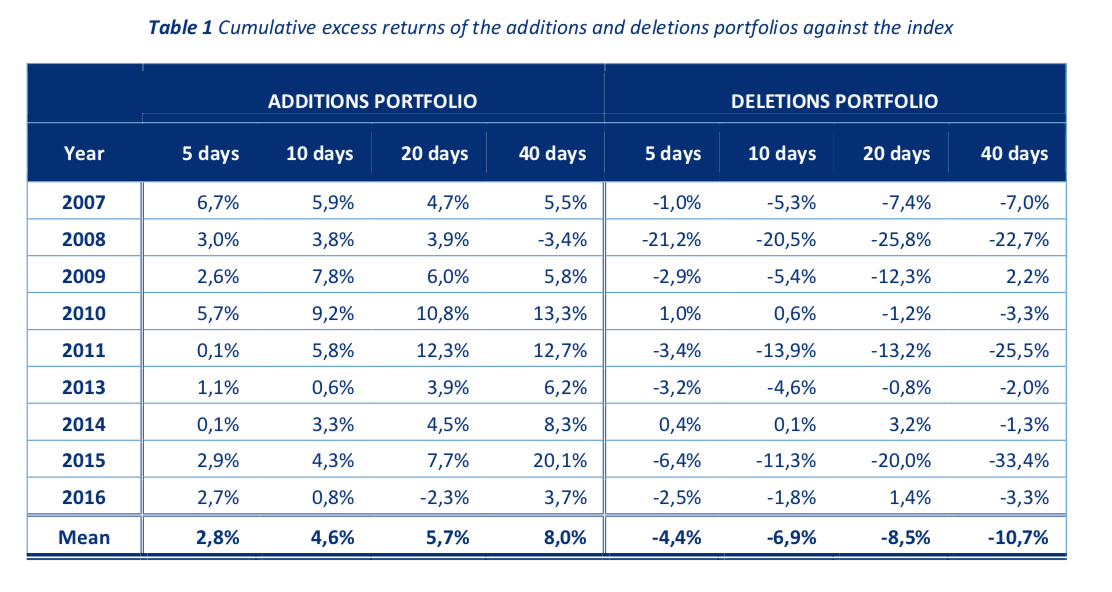

Using a Eurozone blue-chip index, Solactive found turnover costs are significantly larger than zero. Studying the turnover costs for nine ordinary rebalancing days, it found average turnover costs range from 12 to 36 basis points. In other words, they double the management fee for an average European ETF.

"The average turnover costs are the highest for the 40 days lookback period with 35.50 basis points. The shortest considered lookback period exhibits considerably smaller average turnover costs of 12 basis points," the report said.

"This is due to the fact that the additions have already outperformed the index well before the actual rebalancing. This supports the hypothesis that index arbitrageurs forecast upcoming component changes and trade before the rebalancing and even before the official announcement."

Fixing the problem

Fortunately for investors, there are ways to deal with this. And although these costs cannot be removed entirely, there are ways that they can be meaningfully lowered.

To do this, the report proposed three solutions. First, have multiple indexes in the same geography and market. In other words, have more than one US large-cap index from more than one provider, not just the S&P 500; have more than one Eurozone index, not just the Euro Stoxx 50; and so on.

This would allow assets to be distributed among different indexes, and having greater index variance can lower arbitrage costs by ensuring different rebalancing cycles. It also decreases the possible gains of the arbitrage trade as, in theory, there will be fewer assets tracking each index.

Second, turnover can be lowered by building in turnover constraints into an index's methodology - simple constraints could include rank buffers and weight constraints. Finally, index providers can elongate the buffer time before the rebalancing date. An early announcement of a coming change gives those tracking the index more time to react and deal with arbitrageurs.

"A clear announcement well before rebalancing can help expand the time when the index arbitrageurs make their trades, and consequently dilute the impact on the prices of the additions and deletions," it said.

Whether index providers and ETF issuers, who often self-index, take on this advice remains to be seen.