The culture wars in America are raging like never before. For proof, just see how the US education system has been the subject of intense conflict around issues such as gender identity, critical race theory and the 1619 Project. Sensing an opportunity, both of the main political parties have weighed in.

The Republicans have increasingly focused on ‘anti-woke’ education agendas, with Florida Governor Ron DeSantis recently signing a bill mandating the education of the ‘dangers and evils of communism’ in Florida public schools.

Meanwhile Democrat Governor Jay Inslee in Washington State signed a bill in March that included a mandate for the state’s public schools to adopt a curriculum that is as ‘culturally and experientially diverse as possible’. Amidst such divergent viewpoints, it is perhaps unsurprising that 2022 alone saw the publication of no fewer than three – serious – books on the prospects of a civil war in America. Today, opinion polls for the presidential race are very close, even after Donald Trump’s recent felony conviction.

According to recent data from polling website RealClearPolitics, based on the latest Morning Consult poll in early June, Donald Trump is just one point ahead of sitting President Joe Biden.

For many investors, the leap from visible societal fragmentation to trouble in the economy and stock market is not a huge one to make and yet, counter-intuitively, both stock market history and the nature of the current candidates’ respective economic policies suggest that the November election result may not make much difference on market dynamics.

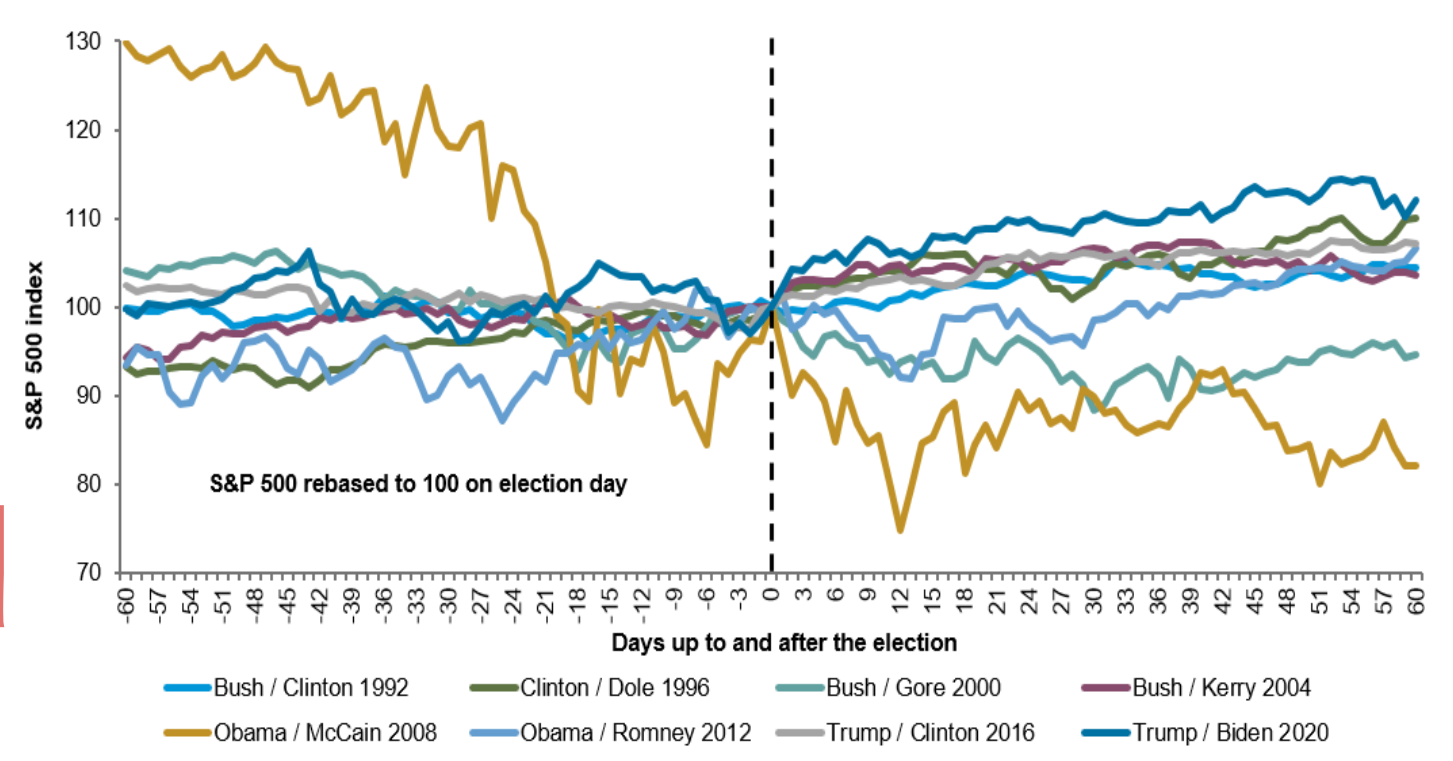

Chart 1: S&P 500 returns rebased to 100 on election day

Source: Bloomberg, GAM

Starting with the history, a brief analysis of the performance of the S&P 500 Index leading up to and following successive elections shed precious little light on the specific role of elections on stock market performance.

A general conclusion might be that US elections have tended to be favourable to stocks, perhaps because in the aftermath the uncertainty after the infamously gruelling marathons that characterise US electoral campaigns is finally over.

But this seems more like a case of conflating correlation with causation. Taking each recent election in turn, 1992 saw America coming out of recession, 1996 saw the start of the technology boom, 2004 saw the market finally recovering from the bursting of said technology bubble, 2012 saw the recovery from the global financial and eurozone crises, 2016 saw the economy and markets boosted by central bank stimulus as China slowed down while 2020 saw both stimulated again by the authorities’ response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

All of these were strong fundamental drivers of positive market performance that seem more persuasive explanations than merely the relief of getting an election out of the way or even elation at the prospect of one candidate’s proposed policies prevailing over another.

If investors require any further evidence that fundamentals, rather than politics, is what matters most, the instances of negative election performance do this convincingly.

While many Democrats will remember with dismay the so-called ‘hanging chads’ controversy that led to the Florida recount in 2000 with disappointment, the stock market was far more focused on the unwinding of the boom in technology stocks, or indeed any listed company that had added a ‘dot-com’ to its name.

The sell-off had already begun in March of that election year and persisted until the invasion of Iraq in 2003. Similarly, 2008’s election was set against the backdrop of the global financial crisis, overshadowing political events.

Perhaps this time will be different, with political polarisation leading to very different economic policy choices between the Democrats and Republicans, and therefore potentially different stock market outcomes.

However, while the rhetoric from the two parties may give the impression of them being poles apart, the actual policy gap is far smaller than most investors would assume.

Consider the trade and tariffs issue. When Donald Trump initially announced import tariffs on Chinese goods in March 2018, there was absolute shock in the economic and finance community.

It seemed to mark a significant departure from the era of globalisation that had begun in the 1990s and which arguably reached its zenith with China’s admission to the World Trade Organisation in 2001.

Yet, protectionist zeal now straddles the political spectrum. Always slightly suspicious of globalisation and its effect on American manufacturing, the Democrats did not outright reverse the Trump-era tariffs.

In this campaign season, Trump has now promised 60% tariffs on Chinese goods and 10% on anything coming in from the rest of the world.

Following a policy review in May, the current White House proposes to raise tariffs on Chinese semiconductors and solar cells to 50%, on syringes and needles to 50%, on lithium-ion batteries to 25% and on electric cars to 100%.

You now have to squint to spot any real differences between the two sets of policies. Investors believing in the positive growth qualities of globalised free markets could be forgiven for not knowing which candidate to root for in November.

Bigger and bigger deficits are the base case

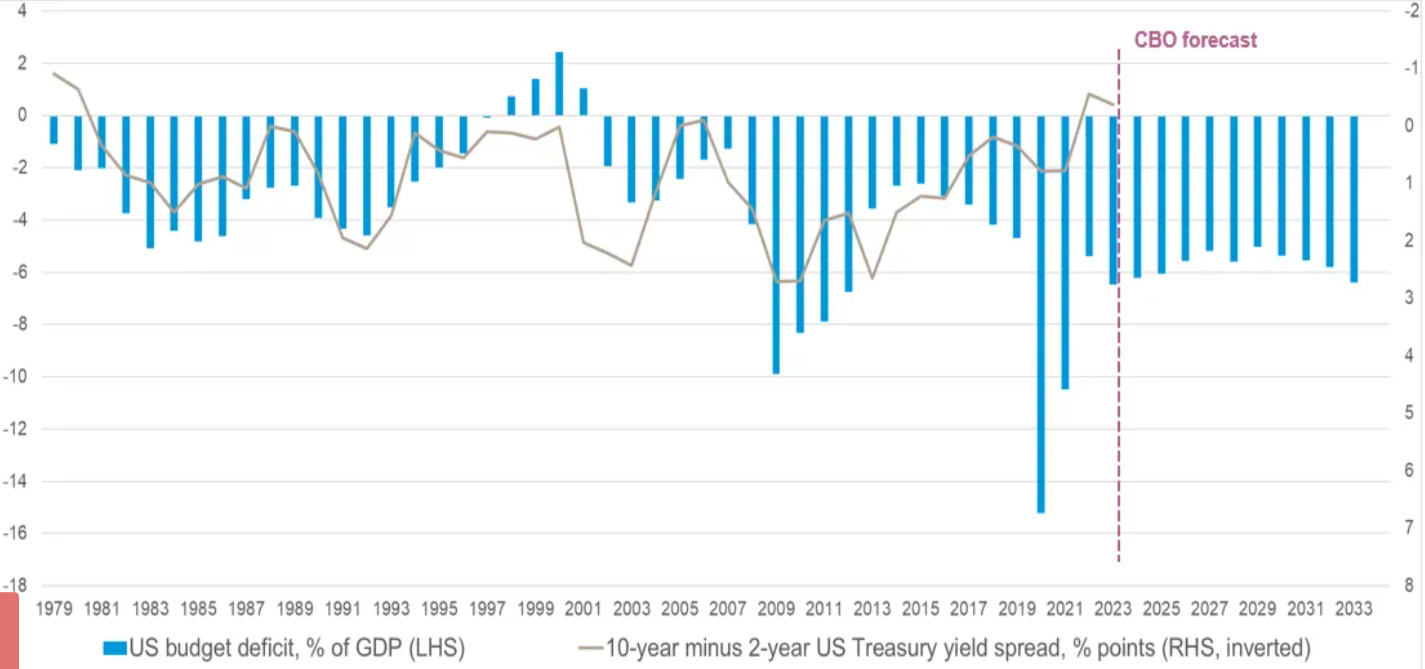

The similarities do not end there either. Take the US budget deficit, which has now ballooned to nearly 6% of GDP as at the end of March 2024, according to Bloomberg, with 3% generally considered a sensible limit.

The potential negative implications are significant. A high budget deficit means that the US Treasury must issue more debt and, along with potential fears that a complicit Federal Reserve could just allow it to be inflated away – though the US Treasury is unlikely to default technically – this pushes up long term interest rates which in turn could depress equity valuations.

Yet, neither party seems especially fussed about addressing the expanding deficit. For the Democrats, pandemic stimulus and demand-boosting initiatives such as the Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS and Science Act are signature policy initiatives which demonstrate the power of centralised government to improve the lives of ordinary Americans.

Conversely, in the event of a Republican victory, the tax cuts brought in for individuals and businesses in 2017 would almost certainly be extended in the belief that unshackling individuals and enterprises from an over-reaching federal government is the best route to strong economic growth and therefore better lives for all.

Thus, while both parties may have different tax and spending agendas reflecting their respective ideologies, both sets of policies are ironically united by the undesirable outcome of an ever-widening budget deficit.

Chart 2: US budget deficit versus 10-year minus 2-year US Treasury yield spread

Source: Bloomberg, GAM

All of these point to some unexpected conclusions. Firstly, economic and market fundamentals are still likely to be the most important drivers for markets, by some way.

Even in the event of a market crisis in the coming months, history suggests that a mere election won’t make much difference – see 2000 and 2008.

Similarly, a continued rally from here shouldn’t be undone by a single presidential contest either – see 1992, 1996, 2004, 2012, 2016 and 2020.

Yes, it is true that 2024’s contest is unlikely to offer the prospect of lower import tariffs and smaller fiscal deficits and in theory, these should be of at least some concern for the reasons explained.

However, since neither has been an impediment to the US stock market’s stellar performance so far – the S&P 500 is up a cool 53% from the end of September 2022 to 5 June 2024 – it is hard to make the argument that they will suddenly become a problem on the 4 November.

This suggests that on balance, investors should not let even this most brutally contested of elections affect their investment decision-making. Amid the spectacle of this year’s contest, they might perhaps be grateful of this rare consolation.

Julian Howard is chief multi-asset investment strategist at GAM

This article was originally posted as an insight by GAM Investments