A few weeks ago I made the case for investing in shares for the long-term, arguing the main concession to make – sitting through inevitable periods of temporary drawdown – is well-known and understood in advance.

For those who are so inclined, the obvious counterargument to a ‘buy-and-hold’ approach is provided by Japan, whose stock market peaked in 1989 and has only just got back to break-even after 35 years in the wilderness.

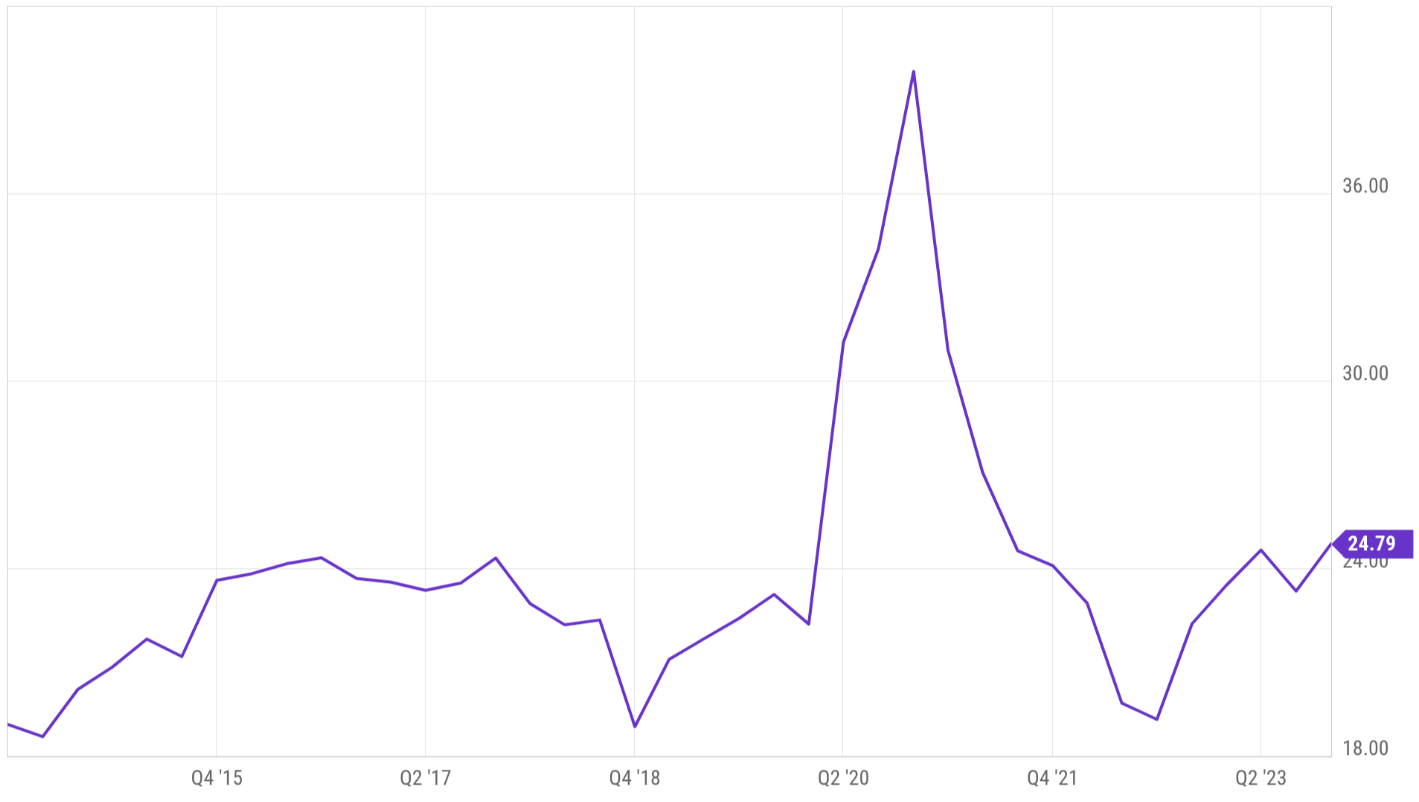

Chart 1: Nikkei 225 returns in Japanese yen, excluding dividends

Source: Yahoo Finance

The year 1989 was notable for many reasons. The Berlin Wall fell. Tiananmen Square. The collapse of Communism. Back To The Future II.

Against this backdrop, Japan was a driving force in terms of economic growth and the global centre of innovation. Japanese cars were a mortal threat to the US automobile industry. The world bought Japanese electronics.

The roaring Japanese economy, combined with a period of relatively easy monetary policy in the mid-1980s, meant asset prices in Japan went parabolic. Property values became so inflated that the 1.15km square grounds around the Imperial Palace in Tokyo were thought to be worth more than all the land in the State of California – an area of 423,970km squared.

As bubbles go, this one was a doozy and when it popped, it led to a couple of lost decades for Japan’s economy and stock market.

Can you imagine what that does to the investing psychology of a country, when your domestic stock market is underwater for three and a half decades? We can preach patience all we want, but everyone has their limits.

So, is this frankly abysmal performance evidence that faith in a ‘buy-and-hold’ approach to investing in equities might be misplaced?

I do not think so. But there are certainly some lessons to learn.

Keep an eye on valuation

In 1989, the Japanese stock market accounted for just under half of the total global stock market. The obvious comparison to make today is with the US, which currently makes up 63% of the MSCI ACWI.

The US is unquestionably the dominant economic force in the world and its stock market includes the largest and best companies on the planet - much like Japan in the 1980s.

However, just because the US makes up such a large proportion of the global market is not a reason to say that it is over-valued. The US has made up more than half of the MSCI ACWI since 2015 and since then has continued to motor ahead quite nicely.

And although the US market does not look cheap by any means, it is nowhere near as expensive as the Japanese market was back in the late 1980s. At its peak in 1989, the Nikkei traded on a price-to-earnings multiple of more than 50x. The S&P 500 currently trades on just under 25x earnings, which is not ridiculous compared to the last ten years.

Chart 2: S&P 500 P/E ratio

Source: YCharts

Based on the more than a hundred years of market data that we have, investing in equities over sensible timeframes – five years at a minimum – has generally generated really positive returns.

If the past is any guide to the future, when you put money to work over these kinds of windows the odds are on your side.

The big exceptions to this rule historically have been in the periods directly following points of extreme over-valuation. The good news is that, by definition, these extreme periods are rare. Japan in 1989 provides us with the classic of the genre.

Do not forget dividends

The eagle-eyed among you will notice that the returns for the Nikkei shown in the first chart do not include dividends.

It is a quirk of financial reporting that returns for most stock market indices do not include dividends – which is strange really, as you are not getting the full picture. Dividends are a key component of overall total returns.

If we include the dividends generated by Japanese companies following 1989, the Nikkei actually reclaimed its 1989 high in 2017, seven years earlier than recent media reports would have you believe.

If you do not need the income that your investments generate, then it is a really good idea to re-invest your dividends ideally automatically.

Buy lobal

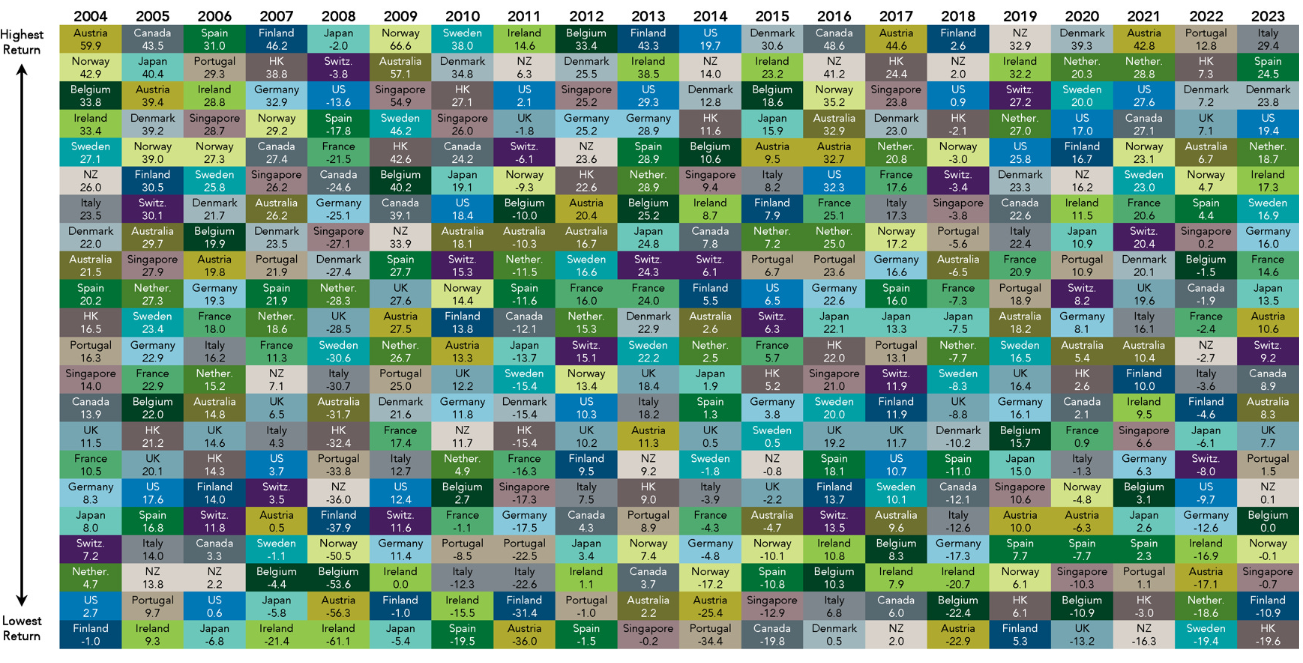

The third lesson to take from the Japanese debacle is to diversify.

In the same way that many individual stocks go through catastrophic drawdowns – that is to say, they fall away from a high point in terms of share price that they never reclaim – bad things can happen to a given country’s stock market and they can spend very long periods of time underwater. Greece is a recent example. Russia is another obvious one.

It is impossible to know where these blow ups are going to happen in advance, in the same way that it is impossible to know which country’s market is going to do the best in a given year.

Chart 3: Annual equity returns of developed markets (%)

Source: Dimensional

Just. Keep. Buying.

The unfortunate soul who chose to invest their savings into the Nikkei in December 1989 and never bought again obviously had a dreadful investing experience.

But most people do not invest like this. They invest gradually, over time, as a portion of their income gets saved and invested into their chosen strategy.

As Ritholtz Wealth Management chief operating officer Nick Maggiulli illustrated in a recent blog, an investor who first bought Japanese stocks at the 1989 peak and kept buying would have only been underwater from the years 2000-2017.

Again, hardly ideal, but what this stat does show is the benefit of pound cost averaging.

For those of us who are earning an income and have surplus left over to invest into capital markets, stock market falls are a Godsend. Until you reach the point where you begin to live off your assets, and particularly when you are young, you should be on your hands and knees begging for lower prices.

As long as equity markets recover their permanent advance by the time you come to live off your assets in retirement, lower prices now mean that you can get the maximum bang for your buck over time.

This is all provided of course that you can stick to the plan. Which is, as ever, the tricky part.

David Henry is a financial planner at Sylva Financial Planning.