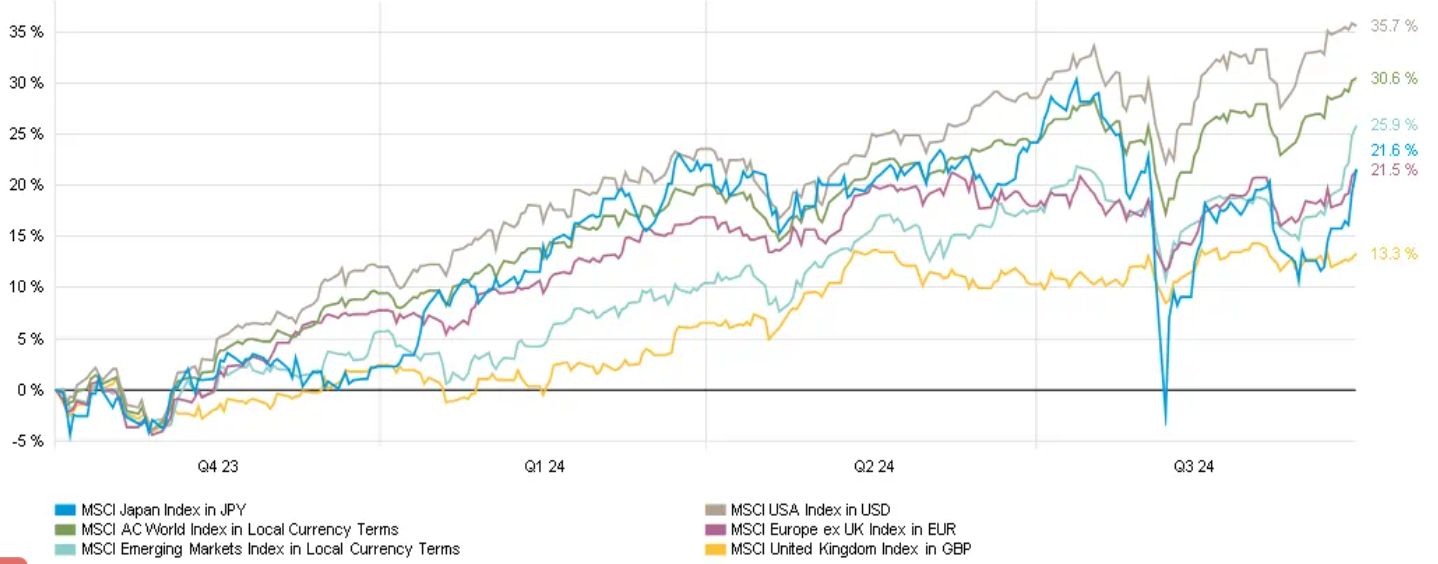

The MSCI AC World Index gained 5% in local currency terms during the third quarter of the year. On the surface this was a strong result and not far off the long-term annualised rate of return investors have come to expect from equities over the decades. But it did mask an episode of heightened volatility in late July to early August whose roots lay in three places.

First of these was a sudden unwinding of technical positioning around the Japan carry trade in which traders borrowed in low-yielding Japanese yen to finance positions in higher-yielding currencies.

The Bank of Japan (BoJ) arguably over-emphasised its desire to normalise interest rate policy and this led to a rapid reversal in positioning as market participants feared a sudden yen strengthening.

Second was fears over the viability of the artificial intelligence revolution. While near-term profitability at the so-called AI ‘superscalers’ – supplying the enabling software and hardware – was probably not in doubt, some concerns were starting to be expressed about the slow take-up of AI across corporate America as well as potential bottlenecks in the huge energy supply required for data servers.

Thirdly, there was the spectre of a potential slowdown in the US economy given that consumers were beginning to express caution in their spending habits. Together, this was enough to see the S&P 500 Index crater -8.8% from 16 July to 5 August, close to outright correction territory.

Stock markets recovered, however, perhaps reassured by the BoJ’s extraordinary declaration that it would not raise interest rates at the risk of upsetting markets.

Nvidia’s stellar results announcement helped too, as did better economic data and cooling inflation in the US, along with the increasing expectation of a 50-basis point (bps) cut in interest rates which was duly announced by the Federal Reserve following the mid-September policy meeting.

Elsewhere, late in the quarter China announced a significant stimulus package which boosted its beleaguered stock markets – and the wider MSCI Emerging Markets index – in the hope that the economy might finally be turned around.

In Europe, the very real prospect of stagnation resulted in the release of a seminal report by the eurozone’s top technocrat Mario Draghi proposing a raft of measures to stabilise and grow the economy in an increasingly uncertain world.

In the meantime, the steady drumbeat of political and geopolitical uncertainty continued. No fewer than two assassination attempts on former President Donald Trump underscored the drama and division characterising this most fraught US election campaign, while the war in Ukraine saw a significant incursion into Russian territory even as Ukraine slowly but surely lost territory elsewhere.

In the Middle East, outright war between Israel and Hezbollah in Lebanon looked all but inevitable. Amid all this, US equities dominated most other regions – yet again.

Chart 1: A US year

Source: MSCI, Bloomberg, GAM

GAM positioning

We did not change our investment views significantly during the third quarter, and sought to continue to take advantage of the superior real returns that stocks can offer over time, with intervening volatility addressed by sensible diversifying allocations sized according to each strategy’s risk/return objectives.

We remained broadly engaged in equities, with an emphasis on US stocks in particular. This stems from the relative strength of the US economy as well as the US markets’ repeatedly demonstrated advantage in return on equity, innovation and management quality.

Since we cannot by definition favour all regions, our bias towards the US position is offset by more neutral views on emerging markets (EM) and Japan as well as more cautious approaches to Europe and the UK.

While EM including China offer a compelling structural story – and now a significant stimulus package – the latter faces particularly acute challenges which we feel require a more profound change of approach by the authorities.

China therefore offers both upside but also persistent downside risks which makes us cautious around both it as a market and the wider EM index of which it is such a large constituent part.

For Europe and the UK, restoring medium-to-long-term growth presents a similarly momentous task requiring the kind of political consensus that has been notably absent in recent years. Away from stocks, our capital preservation approach rests primarily on fixed income markets.

Our favoured areas include short-dated bond and money market instruments which still offer super risk-adjusted yield characteristics since central banks in the US, eurozone and UK have only just embarked on monetary policy loosening.

We also see some appeal in traditional longer-dated government bonds for portfolio crash protection. Beyond these core fixed income areas, we also see the appeal of selected alternative investments.

We have two areas of interest here: long/short merger arbitrage can potentially generate steady, modest returns from the flow of corporate M&A, while macro investing aims to capitalise on significant moves in interest rates and currencies.

The outlook

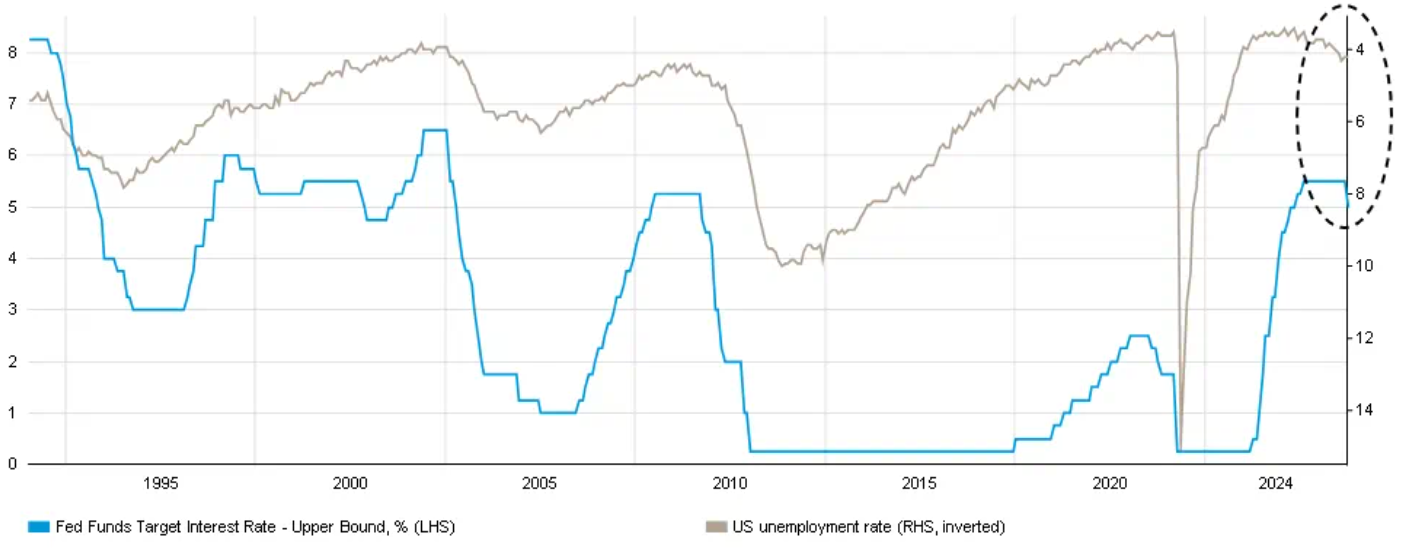

For many commentators, the only question that seems to matter today is whether the US can pull off the vaunted soft landing, a scenario in which inflation eases to normal levels without the economy falling into recession.

Our sense is that this is very possible. Even if US headline inflation stabilises around its current 2.5% rate, the evidence is that the economy should continue to thrive.

Usually, the epicentre of any recession claims due to its close link with consumer behaviour, the employment picture today is attractive. Unemployment at 4.2% remains relatively low by historic standards, labour market participation is rising and job openings are still in good shape, all of which speaks of a growing job market.

Consumers may be a little more cautious, but retail sales are stable and sentiment has been rising for more than two years now according to the respected Michigan survey. All of which leads to the question of what effect will lower interest rates have, if any, on the US economy?

Intriguingly, many US mortgage borrowers are enjoying long-term fixed rates locked in before rate rises began in earnest in 2022. The economy itself seems less structurally exposed to the vagaries of interest rate policy than before – manufacturing and housebuilding are smaller sectors than they were twenty years ago, for example.

Furthermore, cash-generative technology firms that make up an increasing share of the corporate landscape are less capital-intensive than their predecessors.

If anything, interest rates being cut into an already-fair economy risks an unwanted inflationary surge as demand potentially lifts even higher. Also, lower rates will eventually mean lower yields for the holders of the whopping $6.3trn the Investment Company Institute estimates are currently parked in US money market accounts. But these risks seem unlikely to threaten the fundamentally sound US economy.

Away from the US, it is generally harder to be universally confident of benign outcomes. We will watch the progress of China’s stimulus package with interest but note that unless state-directed enterprise and economic management is moderated, unintended excesses will continue to haunt the Chinese economy.

As for Europe and the UK, the challenges have been identified but addressing them requires a degree of unity and long-term planning that have eluded both respectively.

Japan meanwhile looks set to continue struggling with balancing the need for monetary policy normalisation – higher interest rates – with its mighty export sector and the stock market’s addiction to a weak currency.

Predictions around political and geopolitical volatility are by nature challenging. The wars in Ukraine and the Middle East are likely to drag on, particularly if proxies become more enmeshed on both sides.

But investors can at least take some comfort from the fact that the US election will soon be over and that alone will remove an element of uncertainty from the scene. A deep irony underpins the election campaign, in that for all its savagery the two sides’ economic policies are not vastly different when it comes to the budget deficit and protectionism. Either way, with one last quarter to go, 2024 is shaping up to be another American year.

Chart 2: Are rate cuts even needed?

Source: Bloomberg, GAM

Julian Howard is chief multi-asset investment strategist at GAM

This article was originally posted as an insight by GAM Investments