Welcome to the first of our series of myth-buster articles. The aim of the series is to look behind the headlines on ETFs and explain some of the important background that can often be overlooked. We start by examining what is the size of passive investment and what the level of recent inflows might mean for the market overall.

So how much of the global equity market is passive investing now worth?

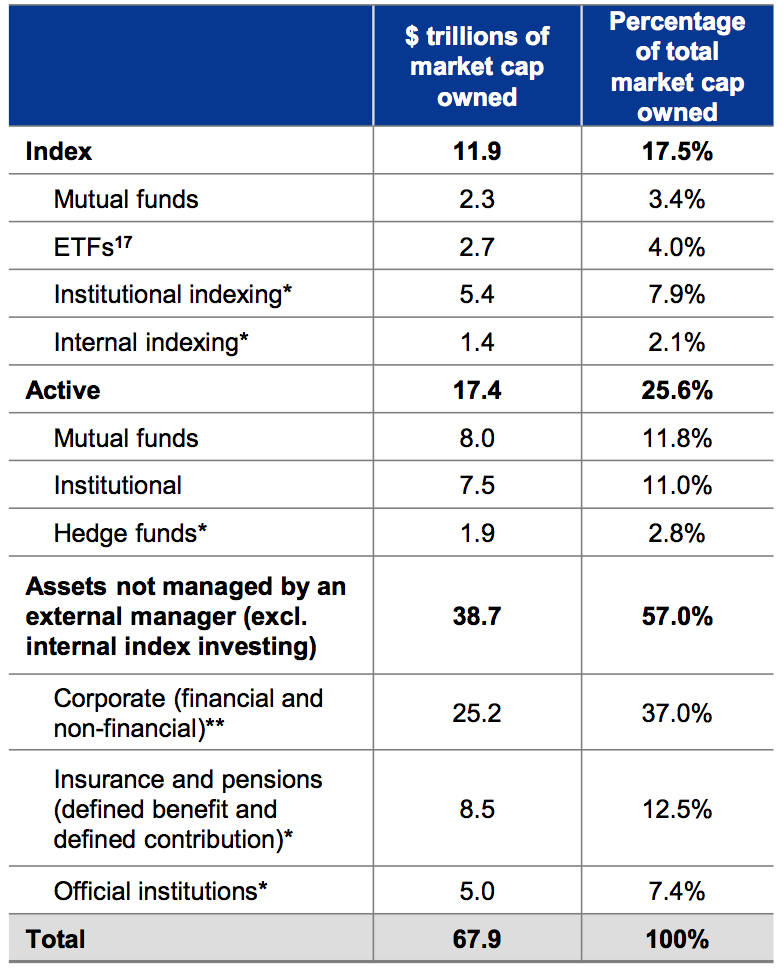

The headlines in the financial pages often make it seem that passive is taking over the world, but the bare percentages make it clear that this is far from the case. Recent analysis from BlackRock shows that the relative scale of index investing is still small - at around 20% of all global equities. In fund terms index and ETFs represent around 12% of the US equity universe and 7% of the global equity universe. But even this simple breakdown might be misleading. Data regarding asset management is sometimes hard to obtain and verify but the BlackRock team make the point that active mutual funds are also a relatively small percentage of the market with the largest percentage of the market consisting of assets not owned by any manager. (See chart 1) As can be seen from the BlackRock chart, ETFs are a very small slice of the overall market at 4% or $2.7bn of the investable equity universe.

But it is growing?

Yes, but there might be a natural self-regulating balance that will apply as and when passives become an even larger part of the market. It is the relative underperformance of active mutual funds which has contributed to the appeal of index strategies; should index funds grow large enough to affect price discovery in parts of the market, then active managers would be able to exploit the mispricing and hence encourage further flows back into active strategies. "Improved active performance would attract flows back into active strategies. Intuitively, the market will continuously adjust to an equilibrium," says the BlackRock analysts.

Still, active funds assets must have been going backwards?

Not necessarily. It is a more nuanced picture, suggest the BlackRock team, with index strategies often being used as low-cost building blocks in actively managed portfolio asset allocation strategies. "Moreover, active funds that have exhibited strong performance net of fees have still been able to generate significant inflows, indicating that this shift is about performance and fees rather than the style itself," they write. The team suggest that investment flows into index strategies are primarily from active funds that are themselves benchmarked to a passive index. In effect, it is hence perfectly possible for that flow to take place in a way that makes zero net change in the demand for given stocks.

So why all the current chatter about passives?

Partly, it might be argued the newsflow at present is reflecting a movement in investment fashion. BlackRock points out that forty years ago, balanced funds containing both stocks and bonds were popular, run in the US by bank trust departments and in Europe by pension funds, banks and insurers. A number of investment professionals then left to create their own firms, mostly to focus on equity funds. Broad equity portfolios were then segmented further, such as by company size, industry, or region. "Over the past few decades, individual investors have moved from owning individual stocks to investing in the equity market via mutual funds," they write. "Most recently, there has been a shift from traditional active strategies towards index."

So it's a fashion thing?

No, this is a question of performance. "Index strategies are often used as low-cost building blocks in actively-managed portfolio asset allocation strategies - which again suggests that active or index are not clear distinctions," say the BlackRock team. "Moreover, active funds that have exhibited strong performance net of fees have still been able to generate significant inflows."

What about the impact of pricing pressure on fees?

What is interesting are the drivers behind the price pressure. While investor enthusiasm for cheaper index products is partly down to underperformance by more expensive mutual fund options, the push and pull on prices is also down to a greater regulatory focus on fees. In the US it has been the Labor Department's mandated transparency on fees on 401k plans, in the UK it was RDR and now across Europe it is Mifid II which are encouraging a greater degree of insight for consumers on what they pay for their investment plans. As BlackRock suggest, many intermediaries involved in offering products to individual investors have interpreted these regulatory actions to mean that low-cost products are a safe harbour. "By choosing low-fee products, they are in essence fulfilling their responsibility towards their clients," they suggest.