The decision on the part of the SEC to approve a non-transparent ETF offering in the US will clearly have an effect on how European regulators view the issue on this side of the pond.

Yet the degree to which the opportunity would be exploited in Europe compared to the evident enthusiasm for the move in the US is more open to question.

In terms of moving the cause of non-transparency forward in Europe, as ETF Stream wrote about last week, all eyes have now turned to the Central Bank of Ireland which stated in September last year that understood the demand form the sector for a “more nuanced approach to transparency.

This would involve asset managers potentially only being obliged to make known their holding to the authorised participant and not the whole market.

In such a fashion it would mean that active managers would, as Hector McNeil, co-chief executive and founder at white-label provider HANetf says, benefit from the distribution potential for ETF by also “protect their unique investment ideas” from being copied.

As McNeil adds, the move to allow non-transparent ETF products in the US marks an evolution in the perception of ETFs from being “simple tracking products” to being seen as simply a distribution technology.

This fits in with comments from Peter Sleep, senior investment manager at 7IM who points out that ETfs are in effect, an empty vessel. “They are just the bottle and it does not matter if you put water in it or nitro-glycerine.”

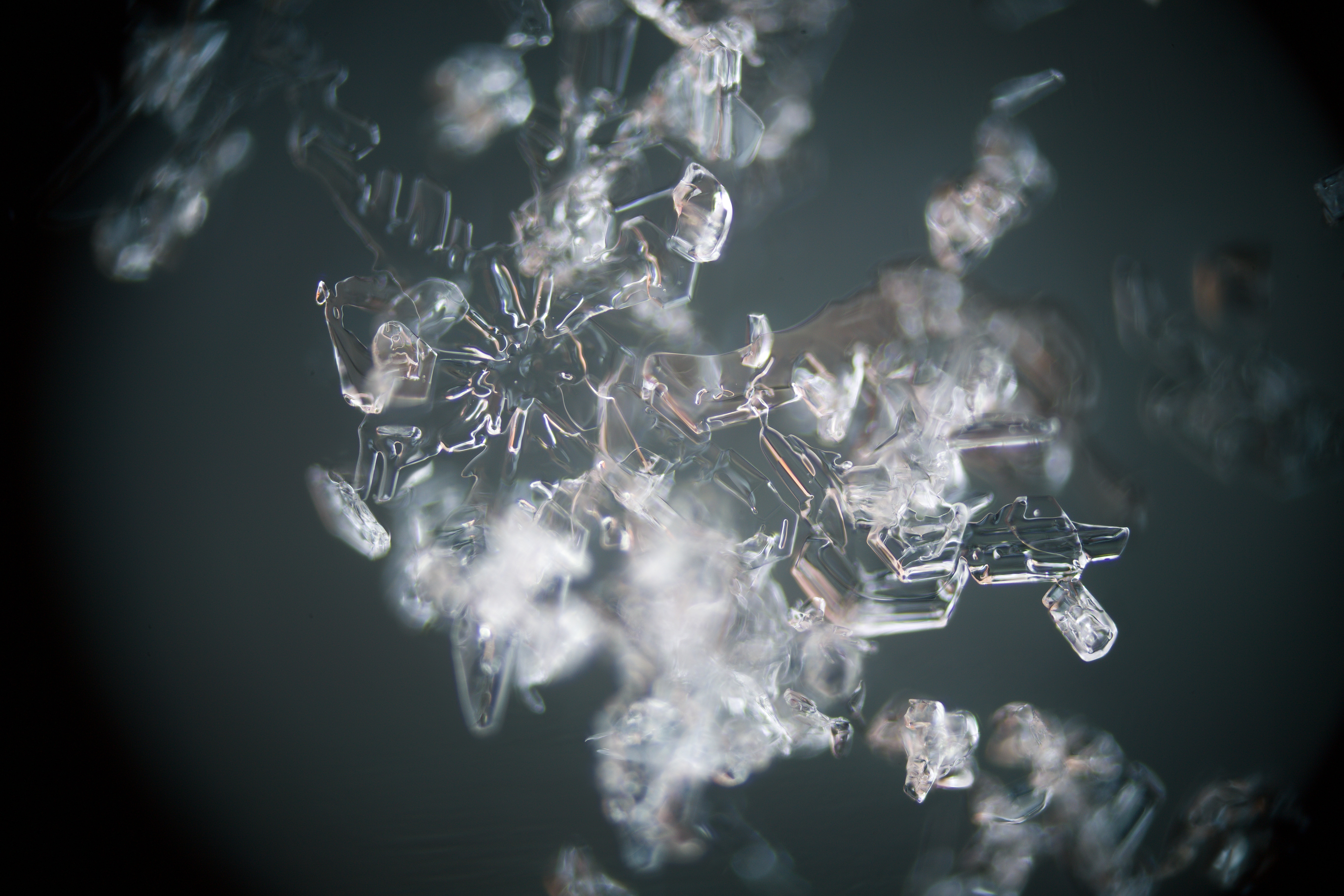

Can you see what I see?

Transparency, according to McNeil, while hailed as one of the most important features of ETFs, is somewhat overrated. “(It) is not an essential component – very few clients will ever ask to see a PCF file, and they do not normally ask twice.”

But perhaps the key point for McNeil is that if the rules on transparency were changed, it would mean that ETFs could compete with mutual funds on a level playing field.

“Limited disclosure has been the norm for the majority of mutual funds sold to institutions and retail investors in Europe under UCITS and this has never curtailed their ability to raise assets,” McNeil says. “As ETFs are UCITS there is no reason why they should be held to a different standard of transparency.”

All of which is fair comment. As Sleep says, “full transparency can make life difficult for PMs that have positions that are ‘sticky’ and difficult to sell. It can lead to front-running.”

Yet, as he goes on to say, even with full transparency, “quants will still be able to arbitrage active funds. They will work out what is being held pretty quickly."

But a potentially more aspect for the European side should a similar approach to non-transparency be adopted is whether the option would be as attractive in Europe as it is in the US.

This comes down to an issue of tax treatment of ETF compared to the shares in a mutual fund. As was highlighted in the recent “heartbeats” furore (or perhaps storm in a tea cup), ETFs enjoy an advantage when it comes to the tax applicable to their sale compared to the sale of mutual fund shares.

A law dating back to the pre-ETF era – indeed, way back to President Nixon – decreed that mutual funds that hand over appreciated stocks to withdrawing investors would avoid any tax liability. The rule was rarely used by mutual funds – investors who withdraw funds prefer cash – but with ETFs, the APs can accept shares in any redemption situation.

Hence a tax advantage is created that might be attractive to mutual fund managers hoping to move an active strategy into an ETF structure.

The lack of a tax kicker will not make a difference to the CBI or any other regulator looking into whether non-transparency of ETFs should be allowable or not. And as Sleep hints, there is no logical reason not to welcome their appearance in Europe or any other market.

It remains the case that investors have to complete their own due diligence into what they are investing in. Yet as Oliver Smith from IG Portfolios says, the downside is that this additional liquidity “may weaken the psychological bond between fund buyer and manager.

“Actively managed products take longer to perform due diligence on, and the liquidity and relative anonymity of the ETF format may make fund selectors quicker to sell their positions in the event of underperformance or to manage daily cash flows.”

Still, as Smith himself says, non-transparent ETFs in the European sector are almost inevitable because they are “just another wrapper” that enable a portfolio of assets to be bought and sold. “From this perspective it makes little difference whether the ETF discloses its holdings or not,” he says, before adding one last potential benefit for those invested in plain vanilla and transparent trackers.

“Those that do should be rewarded with tighter bid-ask spreads and share prices that closer track their net asset values, as the market will reward transparency.”