Once the sole purview of equity investors, the incorporation of environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors is becoming more common also in fixed income instrument valuations, including sovereign bonds.

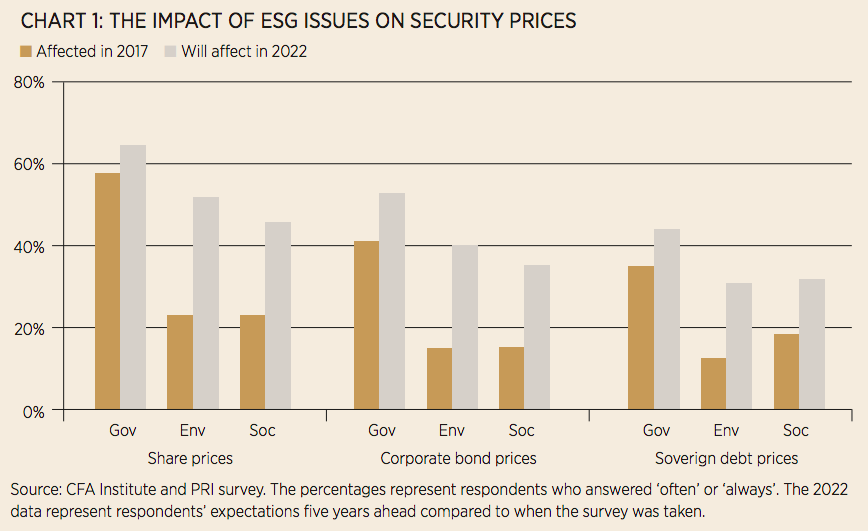

There is growing investor appreciation that a more explicit and systematic consideration of ESG factors can enhance risk assessments even of government bonds and help drive change towards more sustainable growth models (see Chart 1).

Admittedly, the incorporation of ESG factors in sovereign bond analysis is not completely new. For instance, a country’s institutional strength and regulatory effectiveness have traditionally been part of the governance assessment, the factor with the greatest pricing impact; demographic trends and labour market indicators are examples of social factors; and in economies reliant on natural resources and tourism, environmental factors have long been considered.

However, so far, systematic ESG consideration has not been applied to sovereign bonds – traditionally considered lower-risk assets – partly due to a lack of consistency in defining and measuring material ESG factors and generally less developed tools and techniques.

Nuzzo speaking at ETF Stream's Big Call Fixed Income ETFs event on 22 September

Identifying material ESG factors is not easy. Most data are freely available and come from national statistical offices, the World Bank or the International Monetary Fund (IMF)2. However, reporting frameworks that have been developed to help equity and corporate bond investors with ESG incorporation – like the Global Reporting Initiative, the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosure and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board – do not exist for sovereigns.

Furthermore, ESG factors are often interrelated and can manifest through various channels. For example, climate change can have social repercussions (such as community displacement and changing working conditions) and affect various sectors. The relevance of ESG factors varies also depending on the time horizon over which they may materialise or the electoral cycles. Their impact on pricing is difficult to measure, and factors such as inflation and monetary policy change prospects weigh more.

Alongside materiality considerations, there are also practical limitations. German bunds, Japanese government bonds and US Treasuries have a traditional benchmarking role and represent a sizable components of popular government bond indices, for which there are no easy substitutes. It is therefore difficult to apply ESG incorporation in actively or passively managed portfolios. Practices are now changing though:

There is more investor appetite for structured ESG integration, since traditional sovereign credit risk analysis appears to inadequately capture emerging pressures, such as rising inequality and migration flows, resource scarcity, the physical effects of climate change and risks stemming from the transition to a low-carbon economy.

Credit rating agencies are making ESG factors more explicit in credit risk assessments, and are working with the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) on the ESG in credit risk and ratings initiative. They have expanded analytical tools and made organizational changes, including analyst training and the creation of sustainable finance departments.

Policymakers around the world are introducing measures to support ESG incorporation in investment processes. The regulatory landscape is changing fast in Europe but in the United States and in Asia, efforts are also underway.

Finally, ESG indices are beginning to appear for sovereign bonds too; some investors are commissioning customised ones that reflect their ESG policies and objectives.

Assessing ESG factors in a sovereign debt context requires not only profiling a country but also its preparedness to address and mitigate ESG risks, as well as its financial resilience to withstand external shocks and the ability to repay its debt which is different from that of a company. To achieve this, engagement with sovereign issuers can be an important part of the investment decision process in addition to data gathering and analysis2.

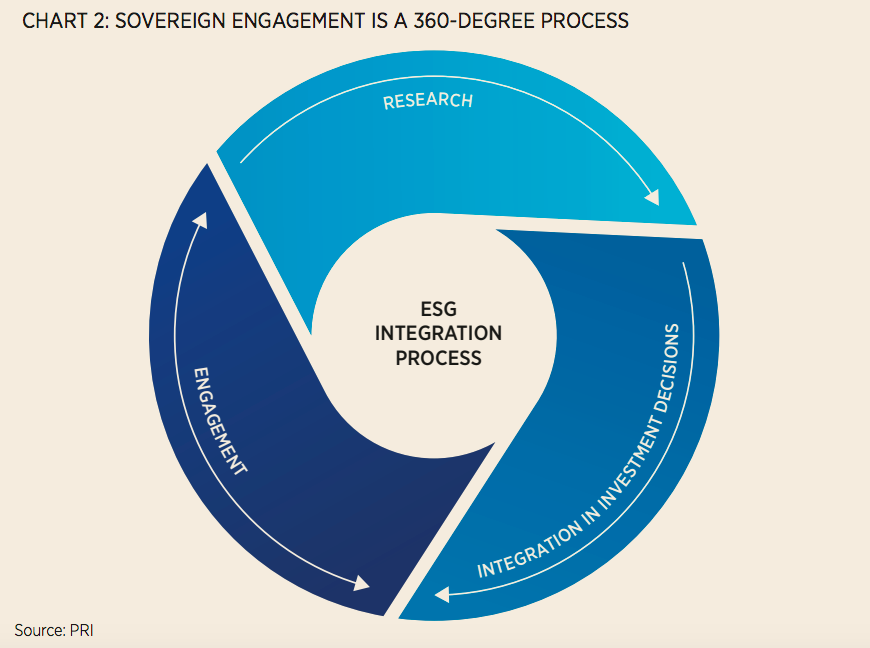

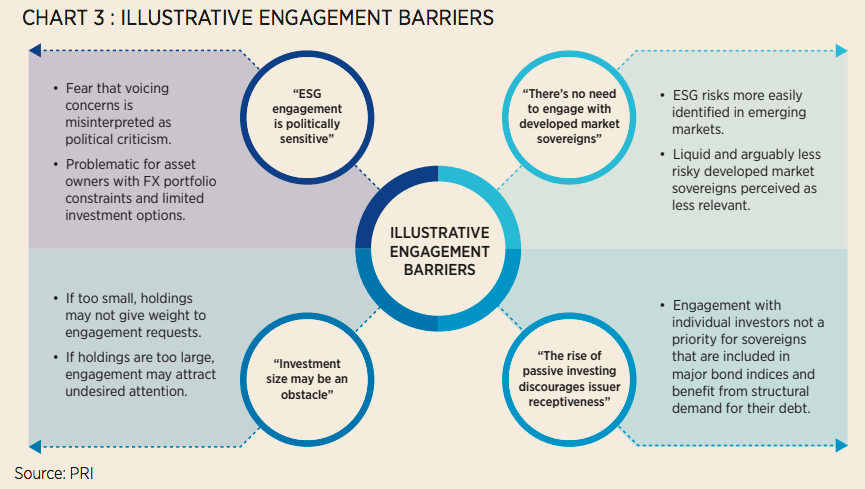

Sovereign bondholder engagement comes with challenges though, and it differs from shareholder and corporate bondholder engagement. Interactions can extend beyond national institutions or ruling parties and include multiple stakeholders (see Chart 2). It is not always possible, and it can be misinterpreted as lobbying, advocacy or an attempt to interfere in government policy choices, especially when it comes to discussing politically sensitive topics such as human rights (see Chart 3).

However, just as bondholders already engage to gain insights around fiscal and monetary policies, they should broaden conversations around ESG topics. Tracking how countries fare on their sustainability pledges and their financial implications (for instance, the Paris Agreement or Sustainable Development Goals) can be a natural non-controversial starting point for discussion.

Importantly, if it is done effectively, engagement can reduce funding costs and sovereign risk. By having two-way discussions, investors can encourage transparency, pointing out which ESG information they deem important for their analysis and conveying expectations. At the same time, governments can demonstrate good governance, through openness to dialogue, and by clarifying policies.

Managing ESG risks in sovereign bond portfolios

With fiscal balances stretched by the COVID-19 pandemic both in developed and emerging economies, adopting a more systematic ESG incorporation in sovereign debt analysis and scaling up engagement has become even more pressing. As funders of sovereign debt, bondholders can play an important role, supporting sustainable funding solutions and increasing the conditionality of future lending, therefore contributing to shaping ESG outcomes, and promoting responsible investing more broadly.

The PRI has started to work more with signatories in this market segment, including the recently launched ASCOR project to develop an assessment framework that enables the current and future climate change governance and performance of sovereigns to be fairly and appropriately measured, monitored and compared.

1. See A Practical Guide to ESG Integration to Sovereign Debt, PRI (2019). 2. See ESG Engagement for Sovereign Debt Investors, PRI (2020)

Carmen Nuzzo is head of fixed income at the PRI

This article first appeared in ETF Insider, ETF Stream's new monthly ETF magazine for professional investors in Europe. To access the full issue,click here.