Born out of a "cultural revolution" and now accepted by the "Visas, Mastercards and Paypals" of this world, the growth of the crypto industry has shocked regulators across the globe. Those are the words Christine Lagarde, President of the European Central Bank spoke in Paris last week.

Joined by Federal Reserve Chairman, Jerome Powell and managing director of the Monetary Authority of Singapore, Ravi Menon,: no transparency, no regulation, no stablecoins or crypto.

"We need to be very careful how crypto activities are taken within the regulatory perimeter, wherever they take place there is need for more appropriate regulation," Powell said.

Menon added "I see more promise in stablecoins", however, this will depend on the "regulatory regime" in place to track them.

Stuck in limbo, Andrew Smith, government and regulatory affairs director for America at GBBC Digital Finance told AltFi that the current US stablecoin regulatory landscape has "proven impossible for folks to figure out".

Across the Atlantic, Smith's colleague Lavan Thasarathakumar, government and regulatory affairs director EMEA at the GDF echoed his sentiment: [stablecoins] are a global technology," he told AltFi, adding that regulatory isolation would only cause greater fragmentation between jurisdictions.

Both Smith's and Thasarathakumar's statements are eerily true. In the US, a slew of stablecoin bills have been proposed to Congress are stuck in deadlock and the EU'sMarkets in Crypto Assets (MiCa)framework lacks practicality. The UK is stuck between a rock and a hard place, trying to remain relevant in the stablecoin debate.

Traditional banks and consortiums are well aware of this and are ready to contest crypto-native stablecoin issuers on the grounds of regulation and compliance as the race for the future of money heats up.

Fed up in the US

In the US, stablecoins permitted to operate and be issued have been called 'payment stablecoins' and 'qualified stablecoins', which must be redeemable on demand on a one-to-one basis in US dollars, must be 100 per cent collateralised in the form of high-quality reserves including cash, cash equivalents or short-term obligations and must provide independent audits of its reserve composition.

Under these rules and directions, algorithmic stablecoins such as terraUSD would not qualify since such stablecoins are not backed by fiat collateral. Other major stablecoin issuers who would not pass the collateralisation test are market leader Tether and Maker DAO's DAI.

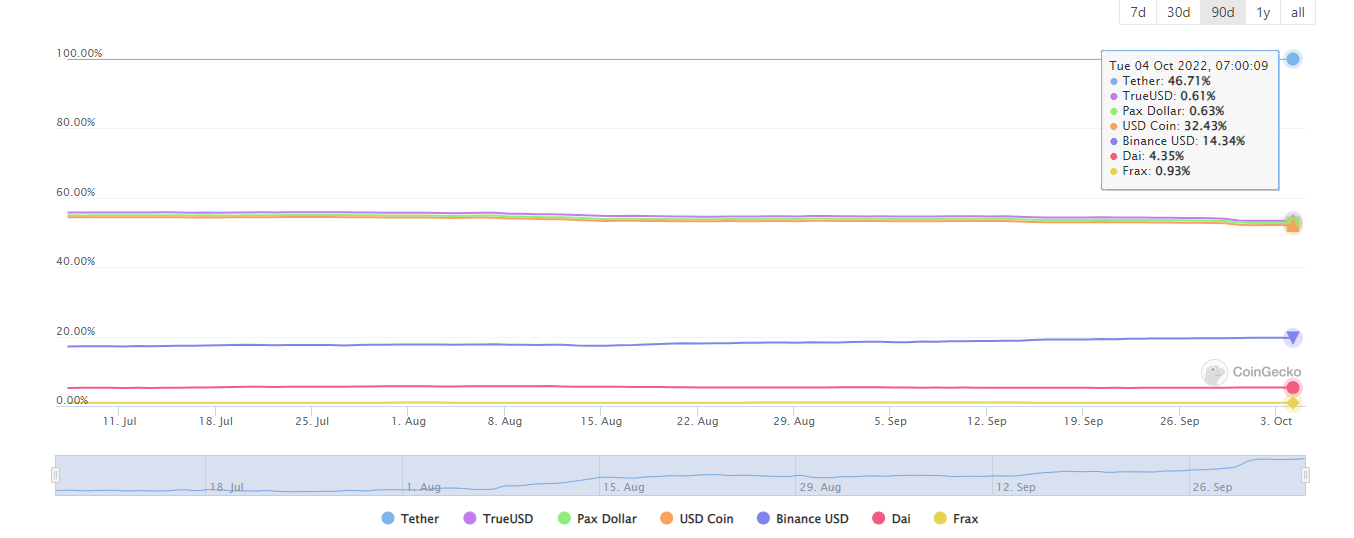

Tether holds8.36% of its reservesin 'other investments' including crypto and DAI is predominantly backed by other cryptocurrencies. Together, both account for50%of the stablecoin market, according to CoinGecko.

Source: CoinGecko

The other two relevant crypto-native issuers areCircle,which operates USDC, the second largest stablecoin by market capitalisation and Binance's BUSD, the third largest. Both stablecoins claim full US-denominated composition of their reserves.

However,Circlecurrently offers a record of theirreserve compositionand BUSD's backing is recorded by Paxos, who are responsible for powering the BUSD stablecoin – raising questions of transparency.

Smith said he believes that if stablecoins are not transparent, backed by high-quality reserves and do not offer instant fund withdrawals, they will "have a tough time complying with any of the popular proposals".

He added: "It seems that either issuers concede here or will be in for a tough time,"

The second crucial development in the US is split between depository institutions and non-depository institutions. Across the seven major stablecoin-related acts unveiled this year, all call for a separation between banks and non-bank issuers, paving a pathway for traditional banks to issue and custody of their stablecoins.

Critically, the right to issue stablecoins revolves around federal deposit insurance, which is overseen by the Federal Deposit Insurance Commission (FDIC). At present, the FDIC hasrefused to insurecrypto-native firms, with allegations suggesting that the FDIC has urged banks not to interact with crypto firms.

There are two reasons why FDIC insurance is paramount to crypto-native stablecoin issuers: maintaining their peggs and the right to custody crypto.

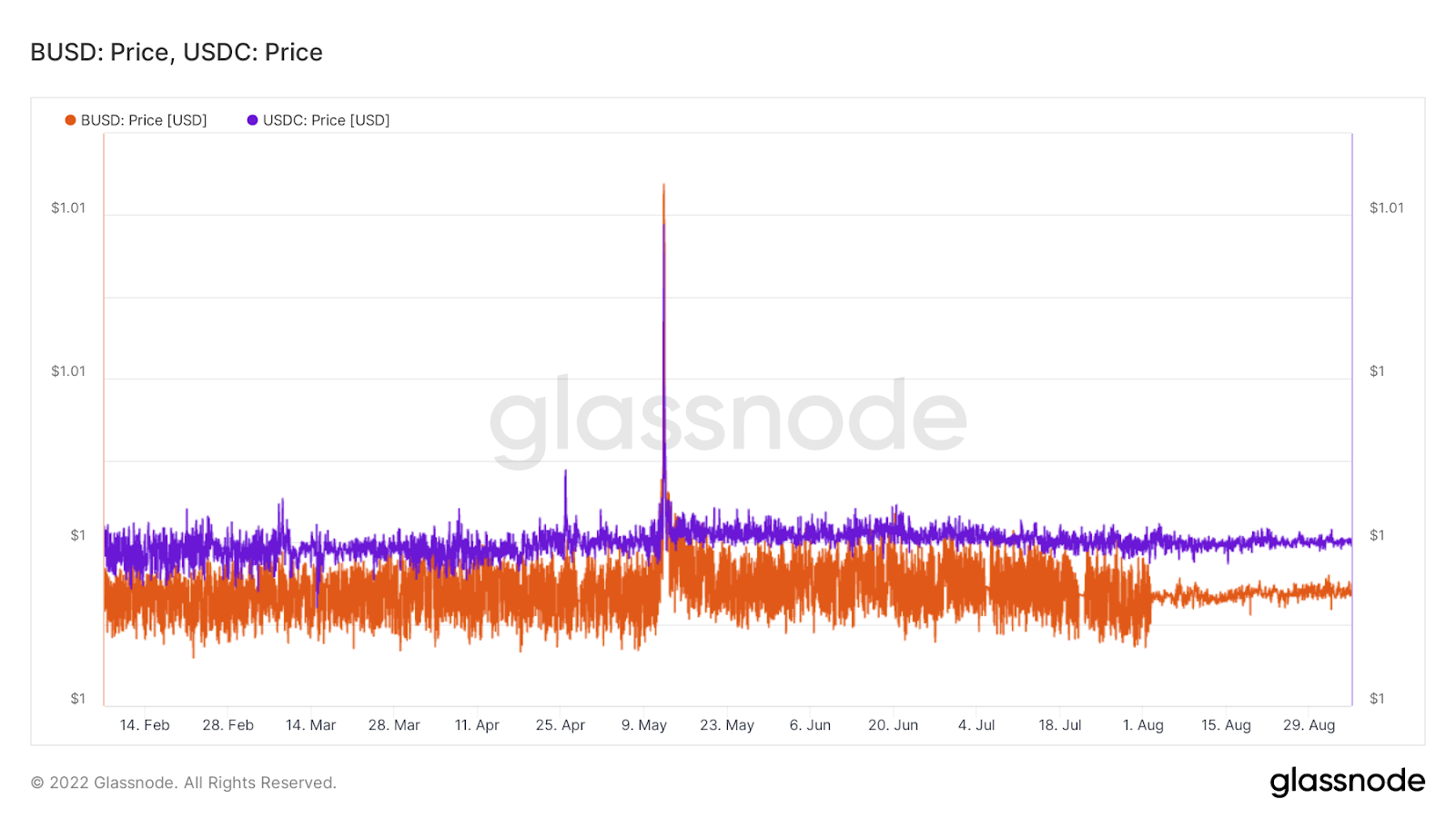

When USDC and BUSD depegged in May, they traded at a premium. Perceived as gold standards, investors rushed to preserve the value of their assets by purchasing USDC and BUSD. FDIC insurance would have allowed them to access the Federal Reserve System, known as a master account.

This means they could have borrowed enough high-quality collateral from the central bank to meet the demand for their stablecoins and so maintained their pegs.

Source: Glassnode

The second reason FDIC insurance is so sought after is the custodial rights it bestows on crypto-native firms. Under theFederal Reserve Act (12.U.S.C. 461(b). (1)), a depository institution is defined as an insured bank, or any other bank which is eligible to make an application to become an insured bank. Quite clearly, if a firm does not have insurance nor is a bank, custody of crypto will be difficult.

Unsurprisingly, stablecoins will and have been vying for their bank charters, which are difficult to acquire, particularly if the FDIC does not wish to insure them. In April, Circle's CEO Jeremy Allairehinted the companywould submit its application to become a chartered crypto bank "shortly".

While crypto-natives are trying to obtain a bank licence, traditional finance consortiums like San Francisco-basedUnited States Dollar Finly (USDF)have joined the race. The consortium is backed by eight FDIC-insured banks and refers to itself as a "bank tokenised deposit", with funds tied to traditional deposit accounts held in bank-custodied and insured wallets.

"Right now the FDIC are taking a cautious and conservative approach in the way they review crypto and digital asset issues with member institutions, especially pertaining to custody," Smith said.

To add to the regulatory disarray, there is an ongoing battle between the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), which views most cryptos as securities and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) which thinks of them as commodities.

If crypto and stablecoins are viewed as a security, then crypto-issuers must comply with SEC rules and regulations. If crypto is viewed as a commodity, then the CFTC's regulation would take precedence – ultimately changing the pathway for stablecoin issuers to obtain insurance and custody of crypto or stablecoins.

"It seems to be the case that there's growing frustration among policymakers on the issue. Eventually, I think the industry runs the risk of having legislators defer to traditional financial services and be done with it," Smith explained.

This sentiment is shared by the Biden administration, which called on Monday for Congress tofinally pass lawson how cryptocurrencies should be regulated.

MiCA and the EU

Across the Atlantic, the European Union (EU) made headlines in June when officials agreed on a provisional version of theMarkets in Crypto Assets (MiCA) framework. Touted as the most comprehensive cryptocurrency framework to date, MiCA will come into effect in 2024.

Like its US counterparts, algorithmic stablecoins are banned from the EU once MiCA is adopted. Additionally, stablecoin issuers must be backed one-to-one by sufficient reserves and deposits, which should comprise highly liquid, minimal market and credit risk instruments. Although not as specific about reserve compositions as proposals in the US are, MiCA will ultimately not be too dissimilar.

Where MiCA does differ is in its definition of cryptocurrencies and stablecoins. Under MiCA, cryptocurrencies are divided into four categories: crypto-assets, utility tokens, asset-referenced tokens and electronic money tokens (e-Money).

Asset-referenced tokens (ARTs), refer to stablecoins that maintain their peg by tracking the value of a currency that is not the legal tender in the EU. e-Money tokens refer to stablecoins that track a legal tender accepted in the EU.

MiCA has taken this position to preserve the monetary sovereignty of the EURO by restricting the issuance and use of e-money tokens in a currency that is not a legal tender in the EU.

"It is important that jurisdictions when they're creating regulations, find allies and remain open to delivering a global standard," Thasarathakumar, government and regulatory affairs director EMEA at GDF told AltFi.

Originally, this protectionist stance was intended to mitigate the risk of ARTs like Meta's Libra from challenging fiat money within Europe. However, as penned by a letter fromthink tanks Blockchain For Europe and Digital Euro Association, the current framework risks banning the largest stablecoins from Europe.

Firstly, under Article 19b, restrictions to ARTs apply when the transactions per day, with a single ART are higher than 1mil transactions or €200m. Today, trading volumes for USDT, USDC and BUSD are roughly $50bn.

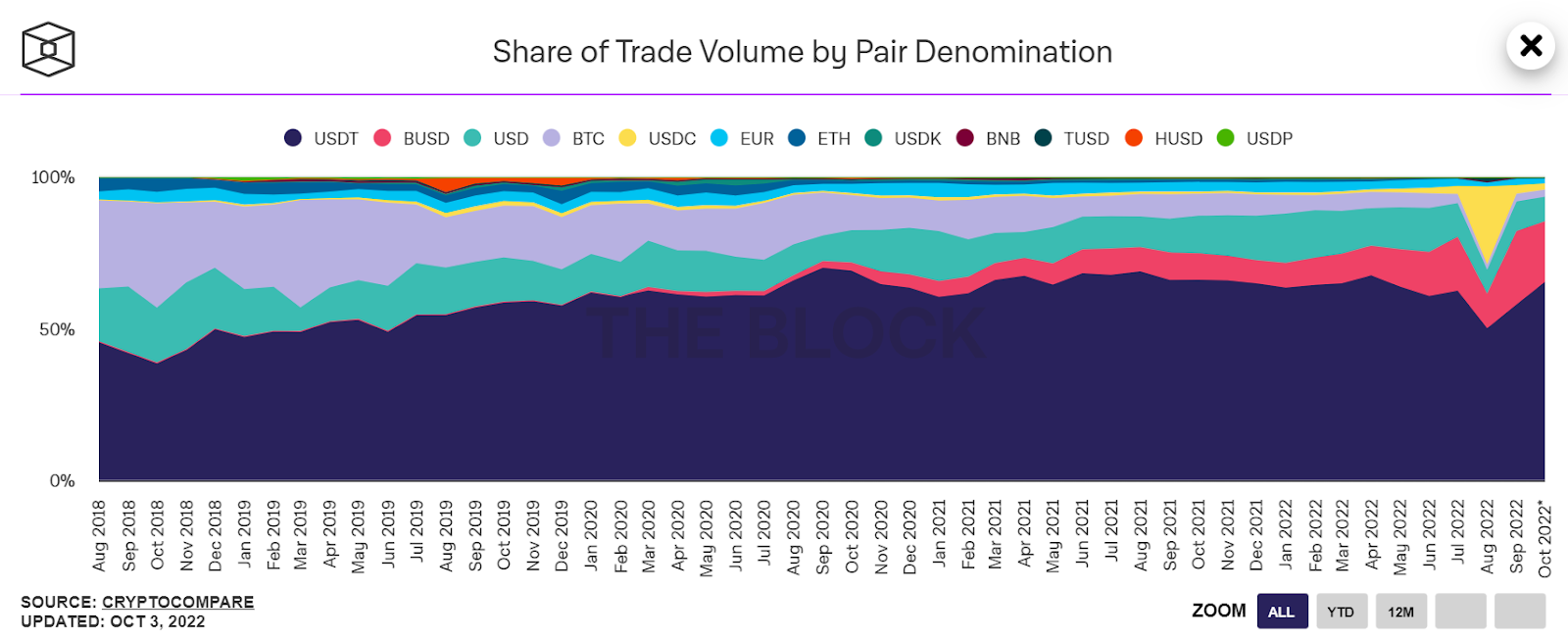

Despite research from Chainalysissuggesting that Europeaccounts for 1/4th of stablecoin trading volumes, this would still be vastly over MiCA's €200m limit. When looking atdata from The Block, Euro trading-pairs account for 1.5% of the market, with US dollar pairs four times as large at 8.06%.

Source: The Block

The second major issue facing stablecoin issuers in the EU concerns custody laws for crypto-asset service providers (CASP). Under MiCA's Article 33, CASPs will only be authorised if they hold a MiCA-approved licence or if their custodian services are carried out by a bank. The banks must only be those authorised in the EU.

"There is no equivalence regime under MiCA at the moment. That makes it difficult since you want to attract business from all across the space, not stop it," Thasarathakumar.

Although Tether has launched its Euro-tracking EURT stablecoin andCircleits EUROC – at present Binance has not launched a Euro stablecoin – the location of their custodians would not permit them to operate in the EU.

Tether and EURT are issued outside the EU. According to Tether's legal terms, its issuer for US customers is served by Tether Limited which is based in Hong Kong and all other customers are serviced by Tether International Limited based in the British Virgin Islands. Simply put, unless they move to the EU, Tether cannot trade its EURT stablecoin.

Despite Teana Baker-Taylor, Circle's head of policy EMEA calling MiCA's "specific regulation" a "good thing", the same issue threatensCircleand its EUROC.

Circleis issued byCircleInternet Financial, a US company. At present, there is no indication thatCircleintends to establish an EU-based group company for the issuance and holding of EUROC.

At present, the only viable potentially stablecoin under MiCA is EURS, the second-largest EUR stablecoin to date. The issuer is a firm called STSS or Stasis, which is headquartered in Malta and as a result fulfilling MiCA's jurisdictional requirements. Despite STSS claiming it is fully compliant with AML and KYC based on a partnership withKPMGfulfilling the role of the independent auditor, it is unclear whether its reserve backing would comply with Article 34 of MiCA.

Subtle efficiency in the UK

In the UK the story is a little different. The Financial Services and Markets Bill (FSMB)proposed in July is a revised blueprint of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000( FSMA), which tries to retain EU law in terms of financial regulation.

Unlike its US and EU counterparts, the FSMB takes a broader approach when defining cryptos, calling them "digital settlement assets" without making a distinction between the types of cryptos available.

Additionally, the governing of cryptos in the UK will be subject to theBank of England,the HM Treasury and theFinancial Conduct Authority,which together are encouraged to operate in tandem when assessing cryptos.

"The UK approach has been to solidify the regulatory perimeter, understanding what can be included and what not and then extending the framework when necessary," Thasarathakumar said.

Additionally, "a sandbox infrastructure" has been set up by theFCAThasarathakumar explains, allowing distributed ledger technologies to test their protocols and frameworks in a regulated and safe environment.

Alongside the FSMB, the Law Commission haspresented a proposalto define and include cryptocurrencies and NFTs into British commercial and common law. Currently being consulted by regulators and lawyers, the 'Digital Assets' framework would be the first of its kind in scope and scale across the EU or US.

Since the FSMB wishes to preserve the financial services and regulatory work laid out in the EU, e-Money token providers are for instance not dissimilar in the UK or EU. Fundamentally, the UK's e-money is an interpretation of the EU's money directive. Earlier this year, the UK moved to include "digital settlement assets" which include stablecoins into this e-money framework.

As Baker-Taylor explains: "USDC and our euro-coin would fall into the existing perimeter of e-money in the EU, which we equally expect will happen in the UK."

The e-money regulation (EMR) gives firms the right to operate as payment institutions underFCAoversight. According to theFCA's register, the only stablecoin issuing firm classified as an e-money provider is Gemini.

Additionally, the UK has opted to have theFCAvet which firms can function and offer crypto exchange services and custody crypto within the country. Again the only recognised stablecoin issuer that has met the FCA'scryptoasset standardsis Gemini.

Despite the UK's seemingly less bold approach to crypto regulation, the country has been a place of strength for traditional financial stablecoin issuers. In the UK, Digital FMI, Digital Pound Foundation and Millicent Labs have all been developing traditional financial sterling-backed stablecoins.

Brunello Rosa, founder and head of research at Rosa & Roubini Associates told AltFi: "The private sector can play the biggest role in stablecoins, especially banks. They do not have the same legal hurdles and are trusted by regulators."

A tough time ahead

Whether in the US, EU or UK, the current regulatory landscape for crypto-native stablecoin issuers is dotted with legal snags. In the US, multiple bills are jostling for Congressional approval, with regulatory bodies from the SEC, Federal Reserve and FDIC all holding different positions when it comes to stablecoins. A lack of cohesion means that traditional financial offerings may very well have the upper hand vs. their crypto-native counterparts.

Europe, despite having a unified front, has opted to promote Eurocentrism, as opposed to taking a globalist approach to stablecoin regulation. Besides posing a fundamental risk to the stablecoin ecosystem, MiCA is hardly forward-looking, potentially shutting itself off to future innovation.

The UK is quietly moving forward with a different approach, one that has previously cost the country business with the likes of crypto exchange Binance but that on the other hand has preserved regulatory and consumer protection requirements. It remains to be seen which major stablecoin issuer becomes the first to custody and exchange crypto within the country.

Across all jurisdictions, traditional financial services offerings are well placed to disrupt the once only crypto dominated stablecoin market.

"We are a long way off before we get this right. Until then I think crypto-natives are going to have to hold on tight, ”Thasarathakumar said.

This story was originally published onAltFias the second part of a three-article series on stablecoins.

Related articles: