Until fairly recently, I, like many investment observers, was wondering whether value investing was dead. In the narrow sense, as defined by one of the founding fathers of the Church of Deep Value, Ben Graham, value has been dead for decade/s.

Anyone searching around for deep value, Graham says, would have spent an inordinate amount of time on a plane to Japan or Vietnam. In fact, one could argue that value stocks were almost non-existent in the developed world (barring Japan), and that it was only in emerging markets where you could find them.

But over the decades, value has been refined and redefined and turned into a systematic strategy more generally, as part of an armoury of styles and risk premia. In this new reading, value investing is a focus on certain fundamental criteria that can be scored using say a Piotroski scoring system.

But fundamental scoring systems can either be complicated – lots of different variables fed into a ranking system – or simple, namely a cheap share price relative to the market. The former methodologies tend to be built around any number of measures but inevitably what tends to dominate is some form of ‘asset’ measure, usually but not always relating to price to book or price to tangible book.

This methodologically rigorous attitude towards value introduces an immediate challenge – namely that we need to use measures that sensibly capture actual tangible assets. However, what happens if those assets are being dematerialised as businesses – under pressure from private equity firms – sell assets and focus on intangibles and intellectual property.

Suddenly, over the last decade or so, we have seen a huge swathe of the public markets either vanish into private hands or become dematerialised stocks with huge intangible books but very little tangible value. In this new normal, anyone seeking true value ends up with either an increasingly small sample size or is required to redefine what value looks like. Which brings us to the second alternative which is to accept looser definitions and implicitly focus on stocks which look cheap relative to other stocks and are also a bit below average on measures such as PE or PBV.

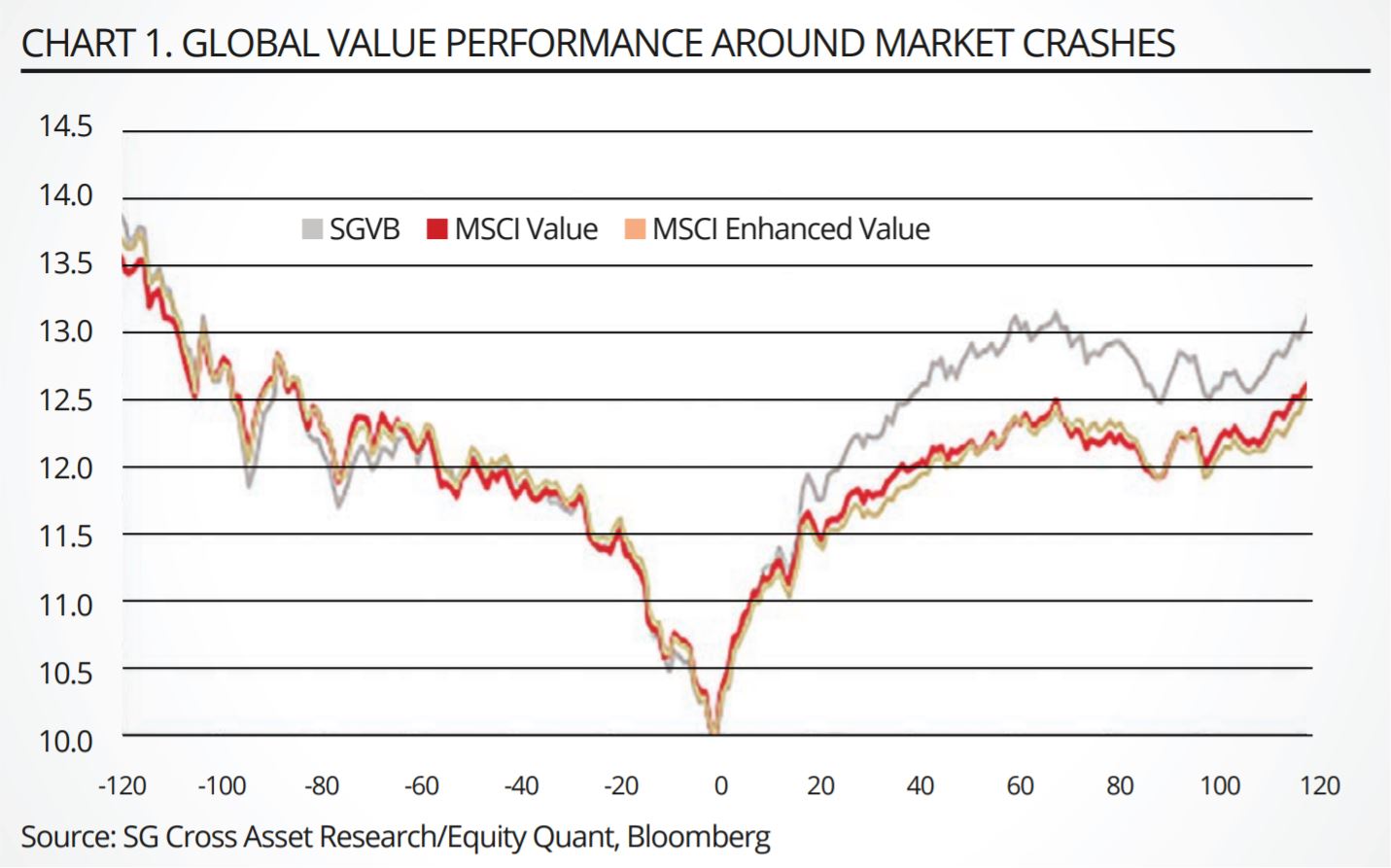

This broader, simpler to understand methodology thus leads us into selecting cyclical stocks such as financials or energy/materials businesses which for various reasons are now ‘out of favour’. This latter focus has of course landed investors in real trouble over the last few weeks as value stocks more widely interpreted had a tough time during the current market rout. According to quant analysts at Société Générale, their version of a value index, the SG Global Value Beta index (SGVB), was down as much as 33.6% in Q1, versus a 21.3% drop for MSCI World (net total returns in EUR).

Value stocks struggling as markets fall is hardly unusual, and as our analysis has shown, value can potentially be a bad thing to own going into the trough of a crash. This is likely because a typical value portfolio tends to include many cyclical stocks, with their prices coming quickly under pressure at the start of a crisis.

ETF Insight: Is the value factor dead?

To add insult to injury we have also seen recently traditional value heroes, such as Warren Buffett (who has in reality in recent decades looked and felt more like a quality investor), turning against many classic value, cyclical sectors, worried about a lack of competitive moat. Cue his recent decision to dump airline stocks en masse.

At some point in mid-late March, it might have been possible to conclude that value investing really was as dead as a Monty Python parrot.

Except that it was not. Because in the last few weeks evidence has emerged that in fact value stocks, more generously defined, have in fact bounced uber aggressively. In fact, according to those analysts at SocGen again, we have recently seen “one of the biggest swings in US value/quality ever and stocks with the worst balance sheets were the best performing stocks during April. The Nasdaq which had been beating the Russell 2000 handsomely this year, saw a 10% relative retracement “in a matter of days”. Chart 1 nicely sums up this astonishing turnaround.

Now, of course, we should always expect style rotations during a stock market cycle and thus this was, on one argument, inevitable, as investors bought into a relief rally. The world really was not ending, quite yet.

The key point here is that value is not dead, especially when the alternative is to buy quality stocks – increasingly tech or brand-focused – which trade at super aggressive valuations. Value lives to fight another day, although of course it also means you might end up in some sectors that would scare the average investor half to death.

There is another story potentially lurking in the weeds around style and risk premia – the size premia. Over the last few decades, investors have come to expect some form of premia for investing in smaller to mid-cap stocks. The extra risk and volatility has been rewarded by extra returns.

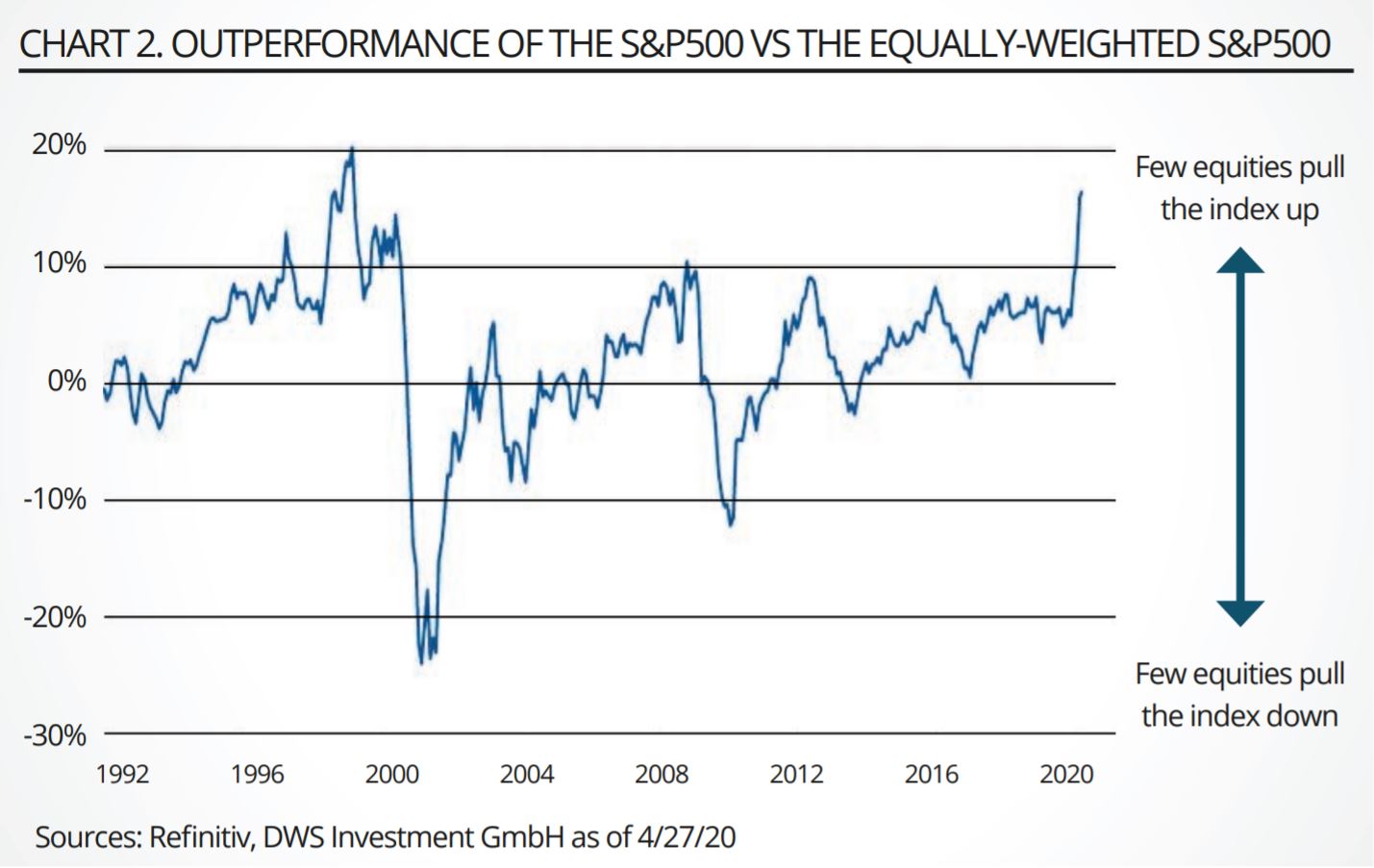

But over the last few years that premia has begun to fade away in core markets, as we have seen a form of winner-takes-all thinking take precedence. In simple terms, various structural factors have given mega large caps a distinct advantage which has flowed through into stronger share price strength, in relative terms. And that trend has been turbocharged in recent weeks. Charts 2 and 3 speak to this remarkable story. Chart 2 is from analysts at DWS, and shows that within the S&P 500, very large cap stocks have dominated returns.

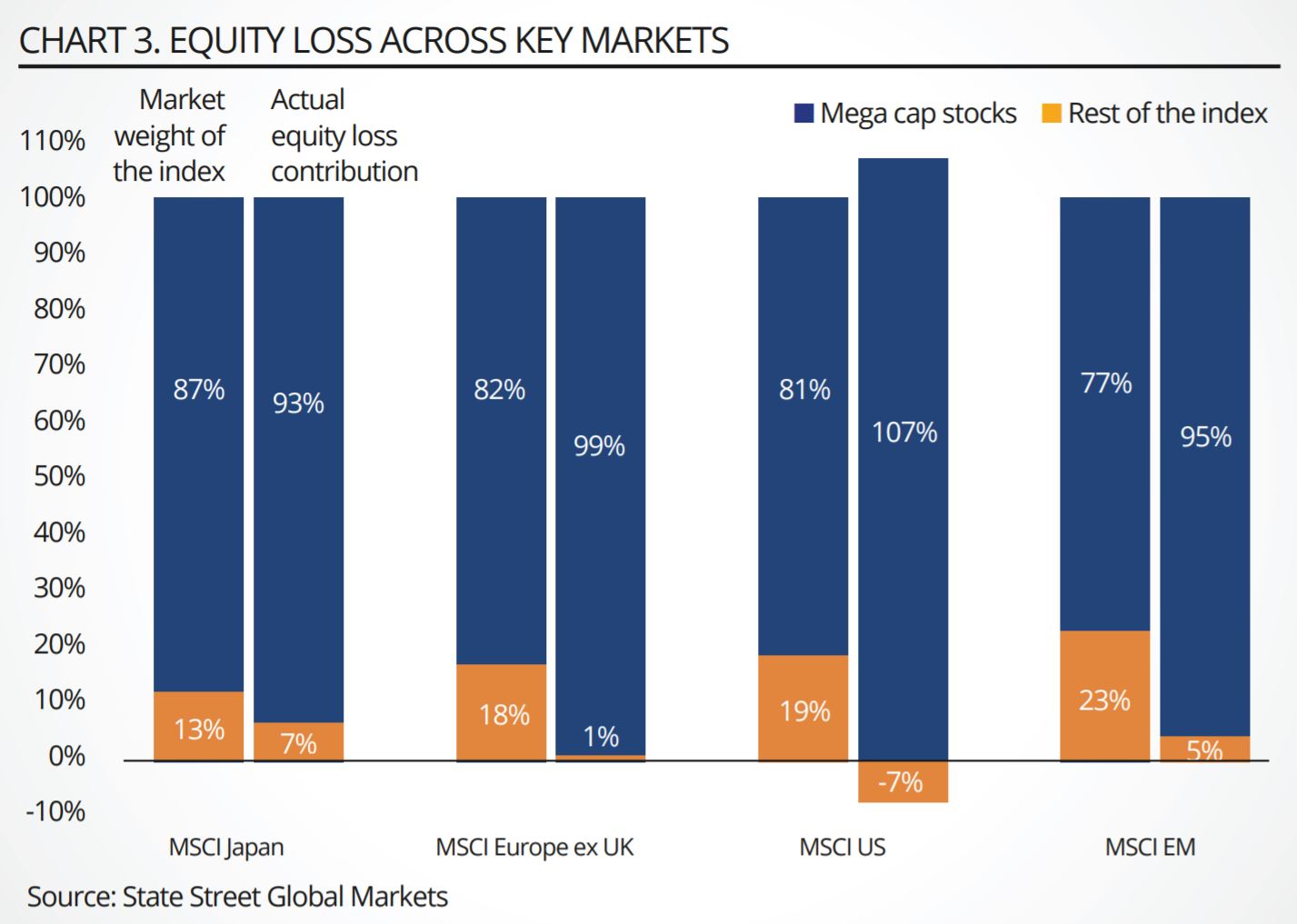

Chart 3 is from Ben Luk, senior multi-asset strategist at State Street Global Markets, and examines the contribution of equity loss across key markets and its impact on the mega-cap stocks vs the rest of the Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI) index.

According to Luk, “the breakdown of the equity loss varied [in the last few weeks] widely between the constituents, with the mega-cap stocks (what we define as the top five stocks across key markets, which makes up to 20% of the index) showing little impact from COVID-19.

“In fact, the top five emerging market companies contributed less than 5% of the index’s loss, relative to its 23% weight within the index. This number becomes more extreme for European corporates at 1% and even more staggering for the US, in which the top five actually recorded a gain but the rest of the index was responsible for 100% of the entire loss.

“While most have suffered due to the virus, the virus has also solidified the mega caps!”

This is arguably the most interesting story of all. Could the size premia and the returns form small-cap investing be about to break down in a new normal of market concentration, post-COVID-19?

David Stevenson is a columnist at the Financial Times and strategic adviser at ETF Stream

This article first appeared in the Q2 2020 edition of Beyond Beta, the world’s only smart beta publication. To receive a full copy, click here.