In a financial world where change is the only constant, some of the tried-and-true principles of asset allocation are ripe for reassessment.

This is especially true for strategies aimed at capturing long-term expected risk premiums and those predicated on dynamic allocation strategies.

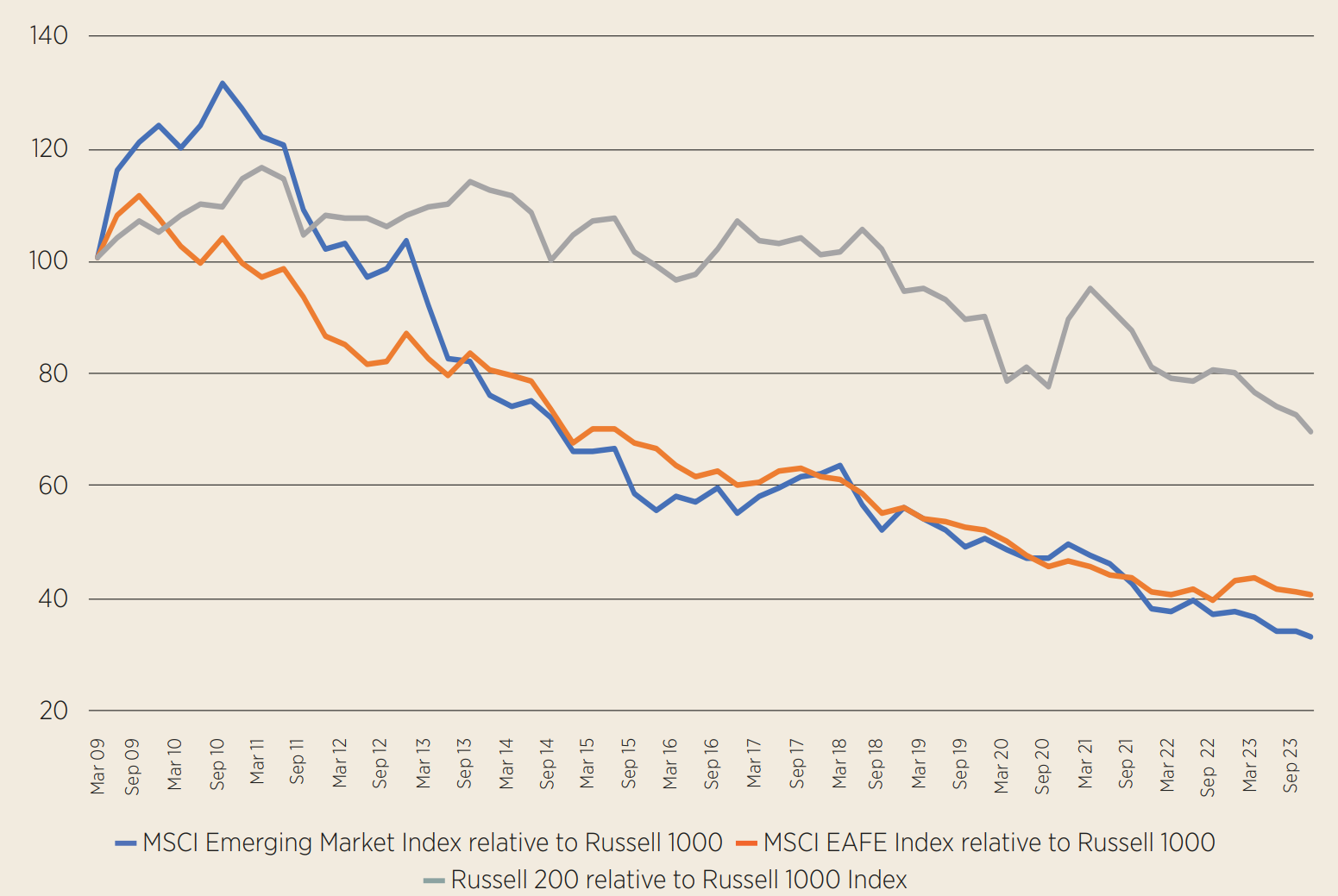

Recent performance data underscores this point. For instance, non-US, emerging markets and small-cap stocks have now underperformed large-cap US stocks by between 30% to 70% since the Global Financial Crisis stock market lows.

Such a stark divergence in performance over such a long period challenges conventional wisdom and suggests it may be time for a rethink.

Modern Portfolio Theory: The rationale for diversification

The age-old adage “don’t put all your eggs in one basket” has long served as the cornerstone of diversification strategies. This principle was formalised by Harry Markowitz’s seminal work, which gave birth to Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT).

MPT argues that by diversifying across various asset classes or securities that are not perfectly correlated, investors can reduce portfolio risk without sacrificing expected returns. Essentially, it offers investors a “free lunch” of improved risk-adjusted returns.

The traditional approach: A mixed bag

For years, one of the primary lessons from MPT has been the diversification of higher-risk assets, such as equities. Investors and their advisors have generally diversified equity holdings by geography and market capitalisation. However, this conventional wisdom has shown its limitations, especially for US investors.

Non-US stocks have lagged their US counterparts by significant margins for a very long time, partly due to the strength of the US dollar but mainly due to the outstanding performance of a narrow group of US-based but globally active companies. Similarly, small-cap stocks and emerging market equities, despite their promise of higher returns, have underperformed. This has left US investors who ventured beyond their domestic market or over-allocated to these “promising” segments sorely disappointed.

Conversely, European investors have found value in a more global allocation strategy, primarily due to the stagnation of their domestic markets. For them, diversifying into the robust US market has generally proven advantageous.

Chart 1: US outperformance over past decade

Source: Parala Capital

The Vanguard paradox

Vanguard – a leader in low-fee investing – strongly promotes disciplined, long-term investing with a preference for harvesting long-term risk premia and shunning dynamic asset allocation. This approach has served them exceedingly well as they have become one of the most dominant financial institutions, an extraordinary achievement for a non-profit.

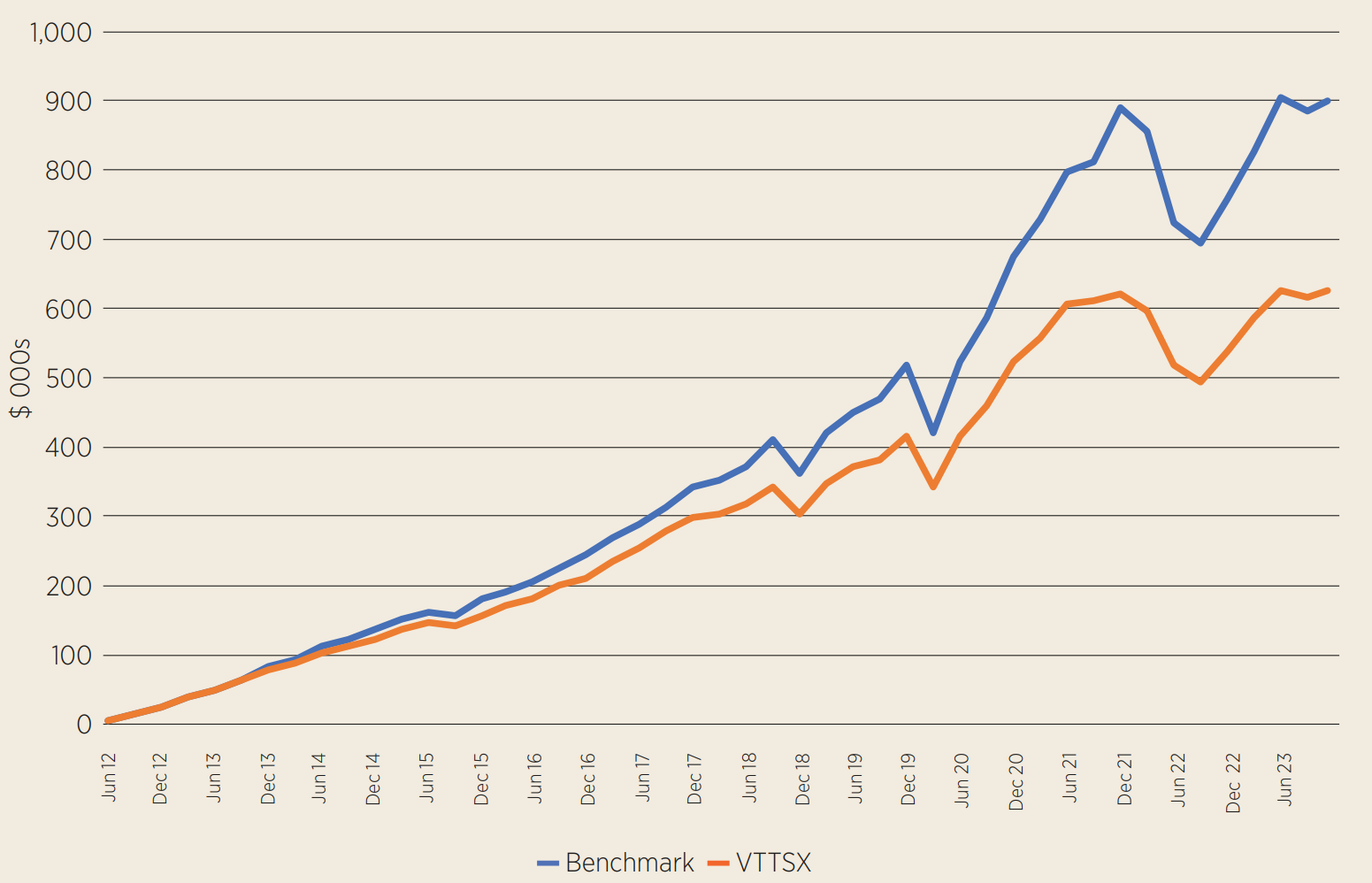

Vanguard’s Target Date 2060 fund, designed for those planning to retire around the year 2060, highlights the potential drawbacks of their investment strategy. The fund allocates 90% of its assets to a broad spectrum of global equities including stocks from both developed and emerging markets across a range of market capitalisations.

However, its performance significantly lags when compared to a simpler strategy focused on large-cap US stocks and US bonds. For example, a consistent quarterly investment of $10,000 in the Vanguard fund starting in the first quarter of 2011 would have grown to $628,691 by the end of September 2023. In contrast, a portfolio with 90% invested in US large-cap stocks – representing over 93% of the US market – and 10% in US bonds – the US bond market size is over $50trn – would have appreciated to $876,474, a difference of nearly 40%. To close this substantial gap, the Vanguard fund would need to perform exceptionally well in the future.

Chart 2: Vanguard Target Retirement fund versus multi-asset portfolio

Source: Parala Capital

The pitfalls of active management

Active managers, who often dynamically reallocate their portfolios across various markets segments with the expectation of outperformance, have also largely underperformed. This trend is reflected in Morningstar’s findings that only 24% of these managers beat their benchmarks globally over the past 15 years, as at June.

Unpacking the underperformance

This raises the question: Is the underperformance a cyclical phenomenon or is it indicative of a more profound shift in market dynamics? Several factors could be contributing to this underperformance.

One possibility is that it is a long-term cyclical trend and we could see a reversal in the coming years. Market cycles often lead to periods of underperformance, followed by rebounds that could favour asset classes that have lagged.

Another explanation could be the increasing globalisation of economies. Companies that establish global dominance might be driving the persistent outperformance of large-cap US stocks. The ‘magnificent seven’ tech giants, which have a significant global footprint, exemplify this trend. Their influence could be skewing overall market performance, making it appear as though US large-cap stocks are the only viable options.

Additionally, the underperformance could be attributed to inherent risks in small-cap and emerging market equities that were previously underestimated. These asset classes may have already priced in factors like political instability, economic volatility, and less mature business ecosystems, thereby offering lower returns than anticipated.

Lastly, changes in monetary policy and trade relations could be influencing asset performance. Central bank actions, such as interest rate changes or quantitative easing, can have a disproportionate impact on different asset classes. Similarly, trade tensions or agreements can significantly affect international stocks, either hampering or boosting their performance relative to US equities.

Rethinking asset allocation: Adapting to a new era in strategy

Given these complexities, investors must critically re-evaluate their asset allocation strategies. The cost of inertia – sticking to outdated assumptions – can be high. It is time to question long-held beliefs that have not delivered for decades and consider more dynamic, data-driven approaches to asset allocation.

Investors should consider adopting a more flexible asset allocation strategy that allows for adjustments based on evolving market conditions and individual risk profiles. This does not mean abandoning the principles of MPT but enhancing them with real-world insights. New metrics, learning algorithms and alternative data sources can offer more nuanced views of risk and return, enabling smarter, more adaptive investment strategies.

While the principles of MPT remain valuable, their application needs a 21st-century update. The cost of inertia is too high, and the need for a more dynamic, responsive approach to asset allocation has never been more urgent. Standing still is the most significant risk of all.

This article first appeared in ETF Insider, ETF Stream's monthly ETF magazine for professional investors in Europe. To read the full edition, click here.