ETFs and their liquidity role in bond markets is still very much a grey area with proponents of the wrapper claiming they can act as a price discovery tool during periods of market stress while critics argue they provide an “illusion of liquidity” by offering easy access to illiquid parts of the market.

In the build-up to March, ETF liquidity was still very much a concern for some investors. An Invesco survey found 80% of developed market banks saw “concerns around liquidity” as a major obstacle to increasing their exposure to ETFs.

When the survey was released later in the year, however, Invesco was quick to point out that although there were some concerns prior to the coronavirus, “it turned out, ETFs performed as you should expect”.

While ETFs remained relatively sanguine in equity markets during the March turmoil, the same could not be said for fixed income ETFs which started trading at record discounts when liquidity in the underlying market dried up.

According to analysis conducted by Citi, some 80% of investment-grade bond ETFs started trading at all-time high discounts to their net asset values (NAVs) including the largest ETFs on the bond market such as the Vanguard Total Bond Market ETF (BNP) which traded at a 6.2% discount to NAV.

Discounts of this kind had never been seen before in the ETF structure and critics were quick to highlight the flaws of the ETF wrapper during periods of market stress.

Highlighting this, one academic study found the rise in corporate bond ownership in the ETF space was impacting the liquidity of the bond market.

In particular, Efe Cotelioglu, PhD candidate at the Swiss Finance Institute, said in the study corporate bonds that are heavily owned by ETFs often share similar liquidity characteristics which could cause problems for investors when looking to exit positions during periods of extreme volatility.

In stark contrast, he found mutual funds did not have the same impact as “managers have discretion in responding to investor flows by buffering cash and trading securities selectively”.

However, this is where the role of the secondary market comes into play for ETFs as highlighted by the Bank of England (BoE) in May which said the ability to trade on the secondary market, unlike a mutual fund, lowers the risk of a fire sale.

One only has to look at the Neil Woodford saga in 2019 or the gating of UK property funds to realise the stark liquidity mismatch between the mutual fund structure and illiquid assets. Any significant amount of redemptions will lead to the manager being forced to suspend trading on a fund leaving investors trapped.

Highlighting the flaws of mutual funds, however, does not leave ETFs in the clear despite the benefits of the secondary market.

As the BoE said in the same report: “If ETF liquidity became impaired in a stress, this would pose risks to any market participants who were reliant on them for liquidity and price discovery.”

The idea of the price discovery role ETFs needs to be explored further. When ETFs started trading at record-wide discounts, ETF proponents such as issuers and experts argued this reflected the price discovery role ETFs play in the market.

As BlackRock said in a report: “Rather than exposing a flaw in the ETF structure, these discounts highlighted how fixed income ETF prices can provide a window into underlying market conditions, transmitting real-time information and providing price discovery for market participants.”

Analysing Europe’s five largest fixed income ETFs during the coronavirus pandemic

In other words, when liquidity dried up, the real time pricing feature of fixed income ETFs reflected the true fundamental value of the market compared to the “stale” NAV which is only calculated at end of the trading day by pricing agents.

However, new research has come to light that shows the situation is more nuanced than BlackRock and other ETF issuers have argued.

In a study entitled When Selling Becomes Viral: Disruptions in Debt Markets in the COVID-19 Crisis and the Fed’s Response, Valentin Haddad and Tyler Muir of UCLA and Alan Moreira of the University of Rochester found ETFs were not a price discovery tool but in fact, a measure of the liquidity premium investors were prepared to pay at that moment in time.

Where the price discovery argument fell down, they said, was in the behaviour of the iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond ETF (TLT) which started trading at a premium to NAV during the heightened volatility. Was this a sign the fundamental value of Treasuries was set to rise? No, it showed the more liquid instrument was the ETF versus the basket of underlying bonds.

“In this case, the NAV experienced larger movements than the ETF price,” the authors said. “This suggests that the gap that opened up between ETF prices and bond prices in their basket was not about slow updating of the NAV, but rather about the more liquid asset, the ETF in this case, trading at lower prices than the less liquid asset, the basket of individual bonds.”

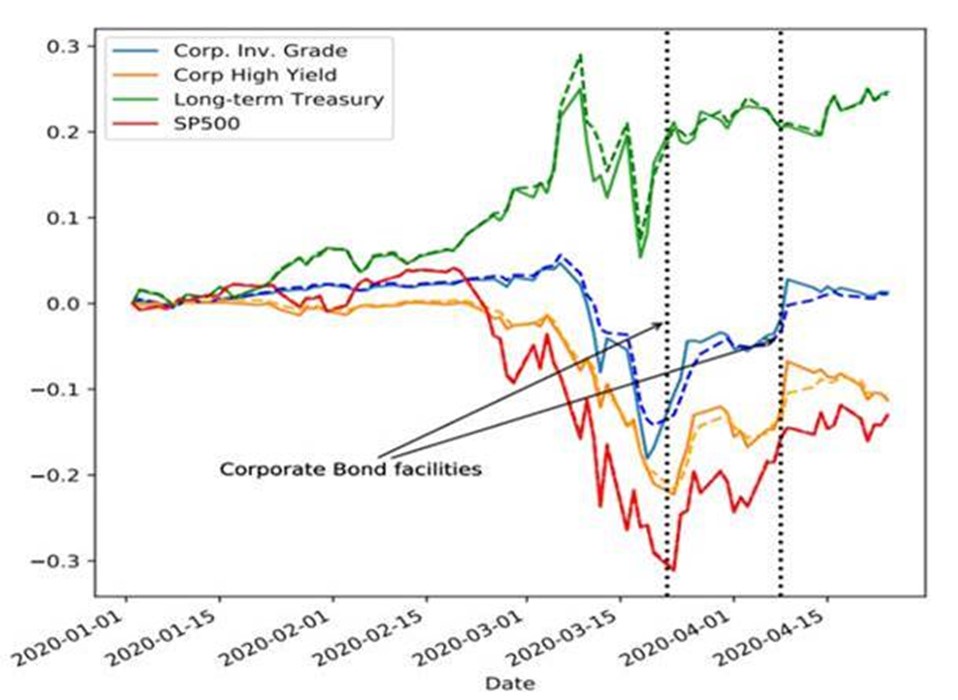

Figure 1: ETF prices and NAV. The figure shows the cumulative log returns for various ETFs along with their contemporaneous NAV-implied cumulative log return for an investment-grade corporate bond ETF (LQD), a high-yield corporate bond ETF (HYG), a Treasury ETF (TLT), and an S&P 500 ETF (IVV).

Source: Haddad, Muir, Moreira (2020)

Authorised participants

Following the March turmoil, ETF issuers highlighted how authorised participants (APs) stayed in the market despite the volatility. According to research conducted by Invesco, the same 16 APs were active across its ETF range for both February and March.

Despite this however, the role of APs in the creation-redemption process is still an area of focus for regulators. In particular, there are concerns APs are not obliged to create and redeem ETFs so, in theory, during periods of market stress, ETFs could be forced to only trade on the secondary market, resulting in wide premiums or discounts to NAV similar to an investment trust.

For the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB), the wide discounts represented friction in the ETF intermediation chain as “APs would normally align prices through an arbitrage mechanism”.

“Low levels of liquidity in the underlying assets may have hindered this arbitrage mechanism, which normally closes such spreads, as ETF prices internalise the low level of liquidity in the underlying bonds,” the ESRB said.

Haddad, Muir and Moreira added: “The [March] episode could be the result of a combination of large selling pressure by investors of safe debt ETFs, and limitations to the ability of dealers to engage in the arbitrage.

“For the latter, APs might have been reluctant to take on those trades due to the balance sheet space they take on, or the adverse selection and volatility risk going with it.”

Their findings follow research conducted by Yao Zeng of the University of Pennsylvania, who argued there was a “conflict of interest” for large banks responsible for the ETF arbitrage and managing their own inventory.

“When the banks’ balance sheets are constrained, they can withdraw from ETF arbitrage,” Zeng continued. “But worse, because ETFs are easier to trade than bonds, APs may even create ETFs for the purpose of managing their illiquid corporate bond inventory rather than for closing the price gaps between the ETF and bond markets, thus further distorting ETF arbitrage and leading to even larger price gaps.”

There is still more work to be done in this area to ensure the creation-redemption process is as smooth as possible during periods of vanishing liquidity.

While liquidity did not disappear entirely during the coronavirus sell-off, it certainly provided a fascinating case study into how fixed income ETFs behave in periods of market stress.

As one industry source said: “No-one is saying the ETF wrapper is perfect, but it is more perfect than other structures.”