LICs are an inferior product to ETFs. Yet ETFs have only just overtaken them in terms of assets under management. Which raises the question: why is an inferior product proving so enduring?

“The report of my death was an exaggeration,” Mark Twain famously said, when a US newspaper following a bout of illness prematurely published his obituary.

Something similar might be said for close ended funds, which are said to be dying as ETFs gain ground.

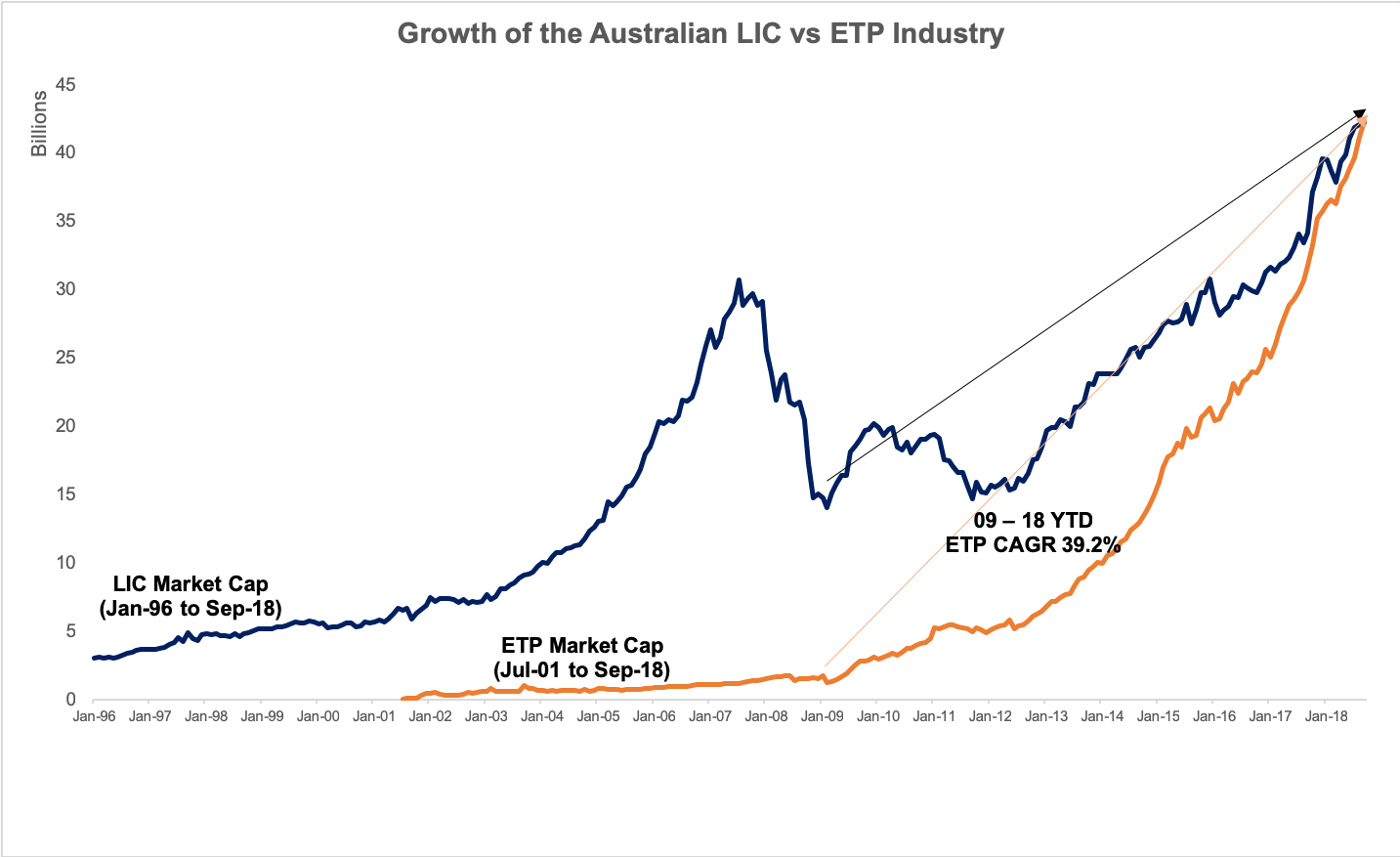

Close-ended funds – called listed investment companies and trusts, or LICs and LITs, in Australia – have lost ground to ETFs the past decade.

In January 2009, following the financial crisis, there were only 23 ETFs listed in Australia. While there were more than 40 LICs. The amount of assets under management in LICs dwarfed those in ETFs: at $14.7 billion compared with just $1.7 billion in ETFs.

Fast-forward ten years and the numbers are very different. As of March 2019, there were more than 180 ETFs while there were only 100-odd LICs. Assets in ETFs had overtaken those in LICs: with $45 billion in AUM sitting in ETFs compared with the $42 billion in LICs.

All of which, of course, gives the impression that closed ended funds are in a state of relatively decline.

LICs: underperforming and overcharging

This picture of decline is compounded when one looks at performance and fees.

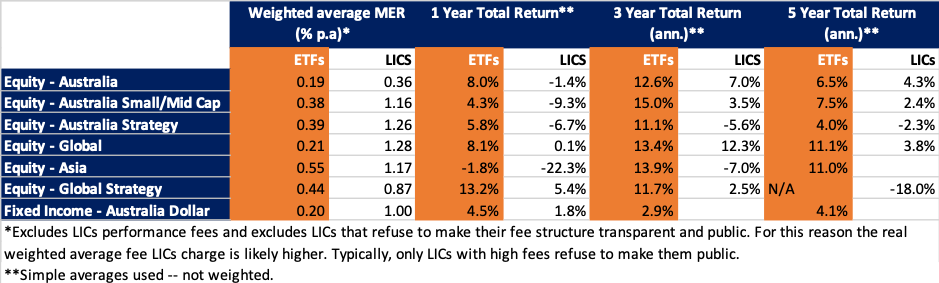

ETFs and LICs both trade on exchange and are grouped by the ASX into common buckets based on their investment strategies, which makes comparing past performance quite easy.

Source: ASX, ETF Stream

In every single category, the average ETF outperforms the average LIC by a comfortable margin. The average ETF does so over every time period for which the ASX provides data.

Not only do LICs underperform, they also charge higher fees. LIC fees are on average more than double those of ETFs.

For global funds, where inflows into ETFs have been most acute in recent years, the fees LICs charge are 6x higher than those charged by ETFs.

Distribution: why LICs persist

Yet this picture of decline of course is an exaggeration. LICs continue to grow at a CAGR of 17%. They also raise money at light speed. To cite two examples, Neuberger Berman recently launched their high yield bond fund as a LIT. They raise over $400 million day one. Similarly other LICs/LITs have raised over $300 million on day one, like L1 Capital and Tribecca Partners. In the ETF industry, putting up these kinds of numbers typically takes years.

Which raises the obvious question: why are LICs still in the game given their inferiority? And why isn’t news of their demise true, rather than an exaggeration?

Here the answer may have something to with the fees and commissions they pay to brokers, advisors and other institutions. When a new LIC comes to market, it will typically pay those who help sell it to their audience. Sometimes called placement fees or sales commissions, LICs will pay brokers and advisors to push their products to their retail clients.

And they pay handsomely. As Cristopher Joye at the AFR notes:

“There has been a tsunami of new [LICs and LITs] launched since 2017, raising more than $6 billion for fund managers who have paid brokers/advisers enormous sales commissions of up to 3%... In dollar terms, fund managers have paid more than $150 million in conflicted commissions to get brokers/advisers to push their products.”

We can see what this looks like in real time.

Like many other Australians, I have a CommSec account. Every time a new LIC or LIT is coming to market, I get an email from them. I also subscribe to ETF Watch – another Aussie ETF trade publication. They also email me when new LICs come out. So I sometimes get emailed twice. However, I’m not aware of any such emailing from brokers when new ETFs come out.

It seems likely that as long as LICs and LITs continue to pay fees of 1 – 3% to brokers and advisors, they’ll stay in the game regardless of their inferiority.