If this year has taught the crypto industry anything, it is that stablecoins are far from living up to their name. Considered a flight-to-safety asset, stablecoins are cryptos designed to maintain their value by being pegged to an external asset class, however, if they cannot maintain their peg, what is the point?

Although ‘crypto winter’ might be the epithet applied to the crypto industry’s poor performance in 2022, a more appropriate one may be the ‘great decoupling’. On 10 May, algorithmic stablecoin terra (TUSD) broke from its $1 parity, sank to a 2¢ low and incurred $40bn losses over a fortnight.

As contagion hit, stablecoins decoupled. Market leader tether broke from its peg between 11 May and 12 May, tumbling to a low of $0.956. Over the same period, tether’s fully collateralised stablecoin peers such as US Dollar Coin (USDC), BinanceUSD (BUSD) traded at 1-2% premiums, appreciating above their designated $1 pegs.

Terra’s collapse wiped an estimated $83bn from DeFi protocols, the greatest loss incurred across the space. CoinDesk’s Nathaniel Whittermore said terra marked the “first time a big mainstream audience was exposed to risks of DeFi” and US Treasury secretaryJanet Yellencalled the collapse a “real threat to financial stability”.

When asked why terra collapsed, Jeremy Fox-Geen chief financial officer of Circle and USDC, told ETF Stream: “Terra was fundamentally backed by nothing and so you cannot maintain something with nothing.”

Despite terra’s collapse hitting crypto hard, algorithmic stablecoins and on-chain collateralised (ONC) stablecoins do not pose a systemic risk to the ecosystem due to their tiny market cap. However, offchain collateralised (OFC) like tether and USDC do – making their depegging a big concern for the financial system

Fool’s gold

OFC stablecoins are fiat-backed and can be converted instantly into a fiat-denominated currency. They are considered ‘off-chain’ since they rely on a centralised third-party custodian to manage their reserves and ensure redeemability. Regarded as the ‘gold standard’ among stablecoins, OFCs experience significantly less price volatility than their ONC and algo stablecoin peers.

Henri Arslanian, the author of the Book of Crypto, attributes OFC stability to their fiat-collateralised reserves and redeemability, offering investors “comfort”, “trust” and a degree of regulatory transparency.

“However, fiat-backed stablecoins have their pitfalls. What assets are backing it up? Are the assets independently audited?”, Hector McNeil, co-CEO of HANetf told ETF Stream.

These questions are as valid as any, even with OFCs. tether and USDC’s decoupling in May is a testament to the lack of transparency for the composition of their reserve backings.

Since launching in 2014, tether has been in a sleugh with regulators and critics regarding its reserve backing – not least since its terms of service state that its reserves are under “the sole and absolute discretion of tether”.

So, in an attempt to clear its name, tether started publishing attestations of its holdings in 2021. The most recent report published in May, amid terra’s liquidation, shows that high-quality and liquid US Treasury Bills holdings doubled to 47% from 2021.

However, a third of tether’s reserves remain in non-disclosed commercial paper and 5% are made of crypto tokens. This means tether is not fully fiat-collateralised. Nor is it over-collateralised.

At the time of the report, the volume of tether in circulation amounted to $82.2bn. When compared to its $82.4bn consolidated total asset holdings, tether’s collateralisation exceeds the par value of stablecoins in circulation by less than 0.3%.

As noted by economist Frances Coppola, if tether’s portfolio dropped “even slightly”, the value of the stablecoin would sink below parity and effectively force it to decouple from its $1 peg.

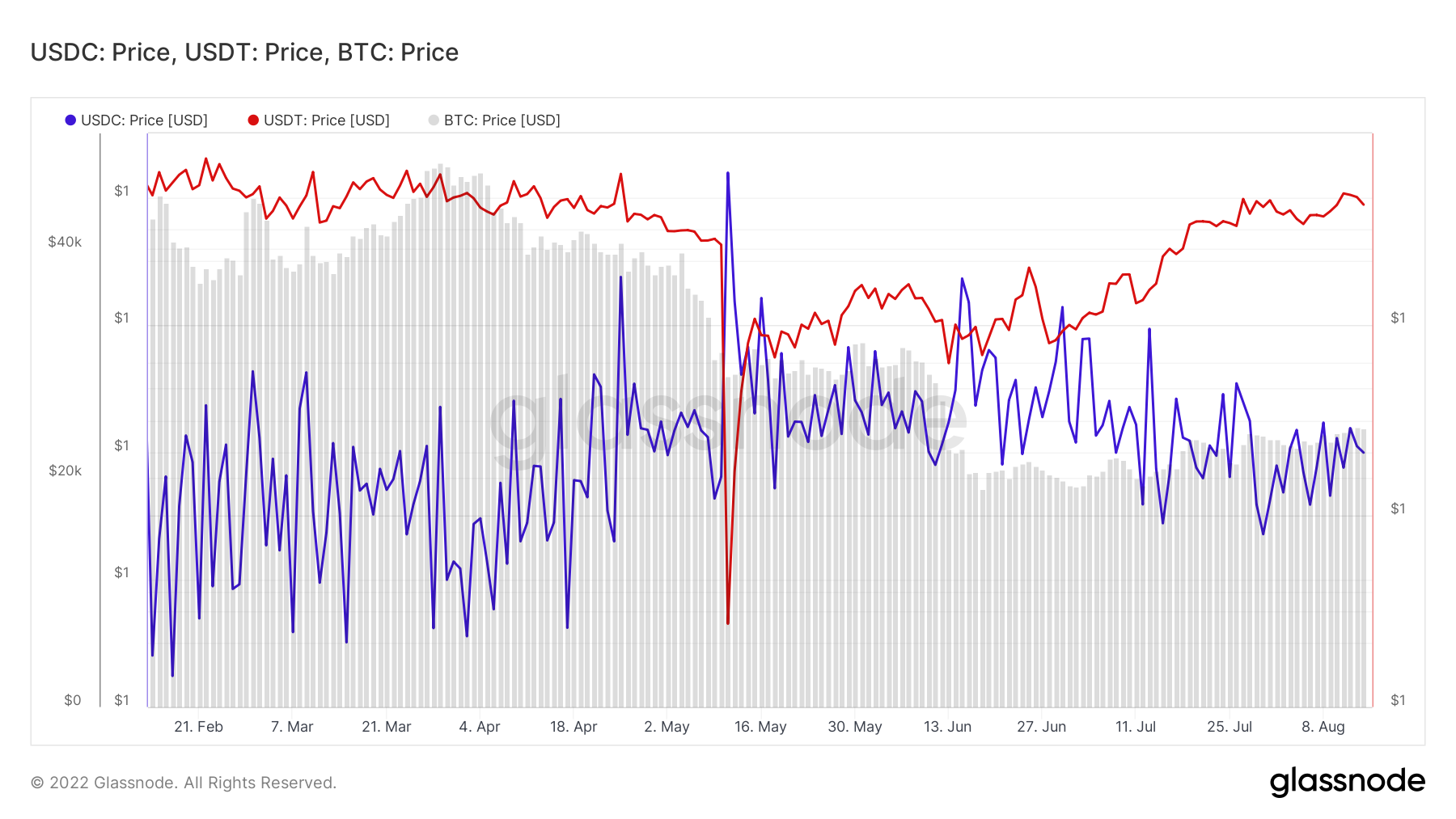

This was exactly what happened during terra’s collapse on 12 May. In light of all the talk of collateralisation and transparency, as bitcoin’s price tumbled by $10,000 between 4 May and 12 May, tether traded to a low of $0.956 and USDC traded at a premium of $1.01, according to data from Glassnode.

Chart 1: USDT falls from peg as bitcoin crashes

Source: Glassnode

Exchange flow data shows an inflow of tether coincided with a large outflow of USDC, signalling investors wished to sell tether and store USDC. This pushed tether’s price below par and pumped USDC above its $1 peg, a classical example of a flight to safety.

But is USDC really safe? While tether’s transparency has been scrutinised, none of its stablecoin peers have fared much better.

Despite Fox-Geen claiming that “we [Circle and USDC] are 100% backed by US dollar-denominated reserves”, monthly audit reports from Circle on USDC only provide reserve account data and are frankly less transparent than tether’s attestations.

In a blog post published on 13 May, Fox-Geen wrote that USDC’s reserves consisted of $11.6bn in cash and $39bn in US Treasuries totalling $50.6bn, the same amount as USDC’s in circulation – making USDC’s portfolio more sensitive to volatility than tether.

Catch-22

If the most reputable stablecoins, collateralised with highly liquid and fiat-based assets cannot maintain their peg, there is little chance that decentralised ONCs and algorithmic stablecoins backed by cryptocurrencies and smart contracts will bring about stability.

If in doubt, turn stablecoin issuers into pseudo-banks and empower traditional banks to issue stablecoins.

So echoes the sentiment of regulators in the US. The Stablecoin TRUST Act of 2022, presented to Congress in April, said stablecoins must be convertible into fiat by a centralised issuer 100% backed by US dollars and high-quality liquid assets.

This definition would only apply to OFC’s such as USDC, not tether.

The highlight of the Act includes a National Limited Payment Stablecoin Issuer (NLPSI) licence that would prohibit nonbank stablecoin issuers from lending or credit activities but would grant them access to a Federal Reserve master account. The second proposed Insured Depository Institution (IDI) licence would allow traditional banks to issue stablecoins.

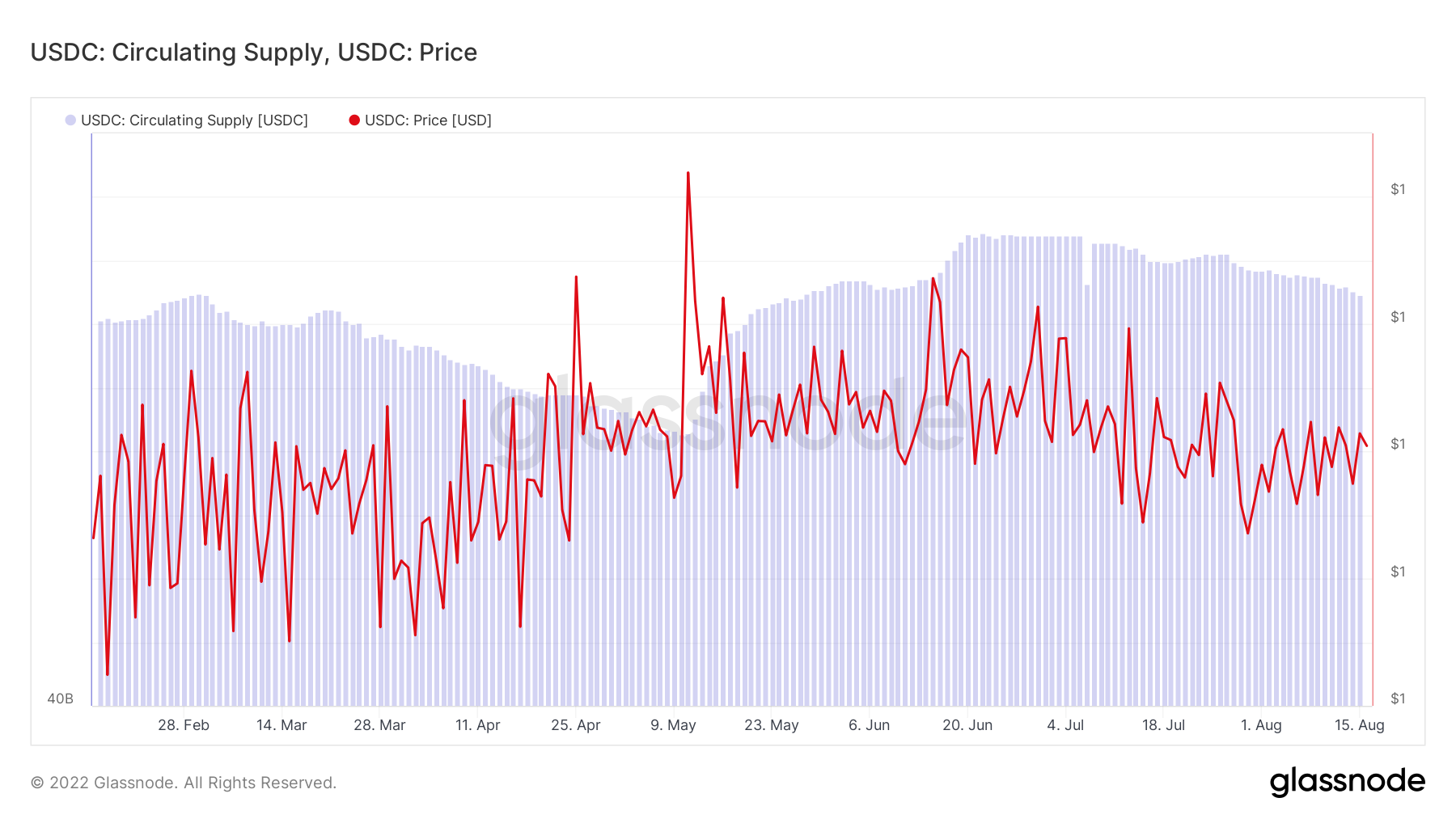

Assuming Fox-Geen is correct when stating that Circle is “100% backed” by liquid dollar reserves, Circle could still not obtain the collateral needed to cater to the demand for USDC – so USDC depegged and traded at a premium.

A master account would have allowed Circle to take loans from the Fed and so over-collateralise to meet demand. But simply having a Federal Reserve master account would not be sufficient.

Chart 2: Circulating supply of USDC vs priceSource: Glassnode

To accept loans from the Fed, Circle would have to have enough high-quality collateral to obtain them, to begin with. Currently, Circle holds $39bn in US Treasuries, not enough to defend its peg and take loans to stabilise its circulating supply.

But none of this matters even if Circle acquired the TRUST Act’s NLPSI licence. The legislation explicitly excludes NLPSI-holders from accessing the Feds lending facilities.

So back to square one.

Circle has decided it would like to become a crypto bank. In April, Jeremy Allaire, CEO of Circle, said the company would submit its application to become a chartered crypto bank, “hopefully in the near future”.

Getting chartered would give crypto banks the ability to accept cash deposits and provide crypto custodial services. In theory, a charter could lead to a master account that would grant access to the Federal Reserve system.

But being a chartered crypto bank does not guarantee access to the Fed’s discount window. Nor do chartered crypto banks and non-bank crypto firms have deposit insurance under the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC).

It just so happens the Federal Reserve announced on 15 August it has finalised a guideline for firms wishing to obtain a master account. The likelihood of getting access will effectively depend on how regulated and federally insured firms are i.e. FDIC deposit insurance.

This begs the question: If licensed banks have master accounts, can access the Fed lending services, are federally insured and can issue stablecoins under TRUST, why have cryptonative stablecoin issuers at all?

All roads lead to Rome

Despite the potential rise of traditional bank stablecoins, few banks are even close to running an operation on the scale attempted by cryptonative stablecoins issuers.

At best, traditional banks are looking to tokenise certain products and systems within their operations.

For instance, in 2019, a consortium of banks led by UBS came together to propose a utility settlement coin USC for cross-border payments and a year later JP Morgan unveiled the JPM Coin for the same purpose.

There is a good reason for this. Even if traditional banks had the regulatory backing and high-quality collateral, they would still not have dominance over both sides of the peg.

As academics Christian Catalini and Alonso de Gortari wrote in a paper titled On the Economic Design of Stablecoins: “The volatility of the reserve asset relative to the reference asset determines how much a stablecoin’s reserve is needed, at a point in time.”

For instance, short-term US Treasuries are some of the most liquid and secure collateral available to stablecoin issuers. Yet, the value of US Treasuries can rise and decline due to interest rate shocks or mass liquidation. In essence, they carry more risk than the asset they are referencing, US dollars.

Ideally, the value of the reserve asset and reference asset is always identical, meaning that the amount of collateral liquidated to maintain parity is always the same and risk-free. This only applies to central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) since the central bank controls both the collateral and the reference asset, hence both sides of the peg.

“If we ever see a central bank issue a stablecoin, that would be as close as we could get to a true stablecoin as they would be managing both sides of the peg,” Lukas Enzersdorfer-Konrad, chief product officer and deputy CEO at Bitpanda, told ETF Stream.

A tokenised US dollar would be virtually void of the risks faced by any crypto-native or traditional bank offering. With 100% reserve backing, unlimited high-quality like-for-like collateral and no exposure to the risks of traditional bank insolvency, CBDCs could defend their pegs and deliver on the promise of stability.

While crypto-native stablecoin issuers come to grips with regulators and banks tread carefully, 105 countries have researched their own central bank digital currency.

According to data from CBDC Tracker, 66 countries are actively researching CBDCs with the Bahamas and Jamaica already launching central bank-backed virtual currencies.

Centralised, government-run and fiat-backed, CBDCs are the antithesis of what stablecoins and, for that matter, crypto is all about. However, all roads lead to Rome and if stability is the name of the game, governments are occasionally best equipped to ensure that crypto investors are not exposed to the terra-fying consequences of stablecoin instability.

This article first appeared in Crypto Unlocked: In the bleak midwinter, an ETF Stream report. To access the full issue,click here.

Related articles