The Year of the Ox was hardly bullish as almost every ETF in the China equity class booked double-digit losses but will 2022 signal the comeback of the world’s second-largest economy?

One of Europe's largest broad-based China equity ETF, the Xtrackers MSCI China UCITS ETF (XCS6), plummeted 21.2% in 2021, its worst annual performance since it came to market in March 2011.

Having followed a fairly predictable path in 2020, investors in Chinese securities faced significant turbulence last year as the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) went on the offensive against the country’s tech giants with more than 50 events of regulatory action taken against software giants for alleged antitrust offences, data violations or attempts to list shares overseas using Variable Interest Entities (VIE).

Responding to this, US investors poured $5.6bn into the KraneShares CSI China Internet ETF (KWEB) over the last six months, making it the largest China ETF in the world at $6.8bn despite falling 57.9% from the end of January last year, according to data from ETFLogic.

In principle, policymaking with the end goal of sustainable growth is admirable, however, when done in rapid succession these policies create uneasiness and doubts about companies’ future prospects.

Tech and policy tussle

Commenting on the CCP’s tech clampdown, Mike Shiao, CIO of Asia ex Japan at Invesco, said the current raft of regulation is intended to transform China’s economy from one driven by its expanding growth sector to one focused on quality and sustainable principles.

He added: “We believe the government has no intention to undermine the sector. Its focus is targeted on the socially vulnerable (i.e. the riders, the parents, and the minors) and the financially risky (fintech and its linkage to broader financial system).

“Its aim is to promote a digital environment that bolsters fair and healthy growth that cares about social wellbeing.”

Looking ahead, Brendan Ahern, CIO at KraneShares, told ETF Stream this year is politically significant for China.

“Many of the top leaders are reaching an implied retirement age of 68 – premier Li Keqiang, vice premier Liu He – so there is a lot sensitivity. Maybe an element of this internet regulation is related to how these potential political changes are disseminated within social media.

“Perhaps this explains why we have seen this regulation pushed through in a pretty short window – it could also suggest we have seen the worst of it.”

With Chinese tech equities having taken a severe hit last year – with many down more than 50% over the last 12 months – the golden question for 2022 is whether these price corrections represent a unique buying opportunity or a midpoint in the cycle of regulatory intervention.

Making the supportive case, Ahern said: “There are only 12 stocks globally with a market cap over $400bn that are growing over 20%. Alibaba is one of them and it has the lowest P/E ratio of the twelve, so you have seen this disparity between the price action and the fundamentals of these companies.”

Shiao agreed, adding improved clarity in the communications surrounding regulatory changes creates “attractive buying opportunities” to companies less targeted by regulatory action such as eCommerce and food delivery.

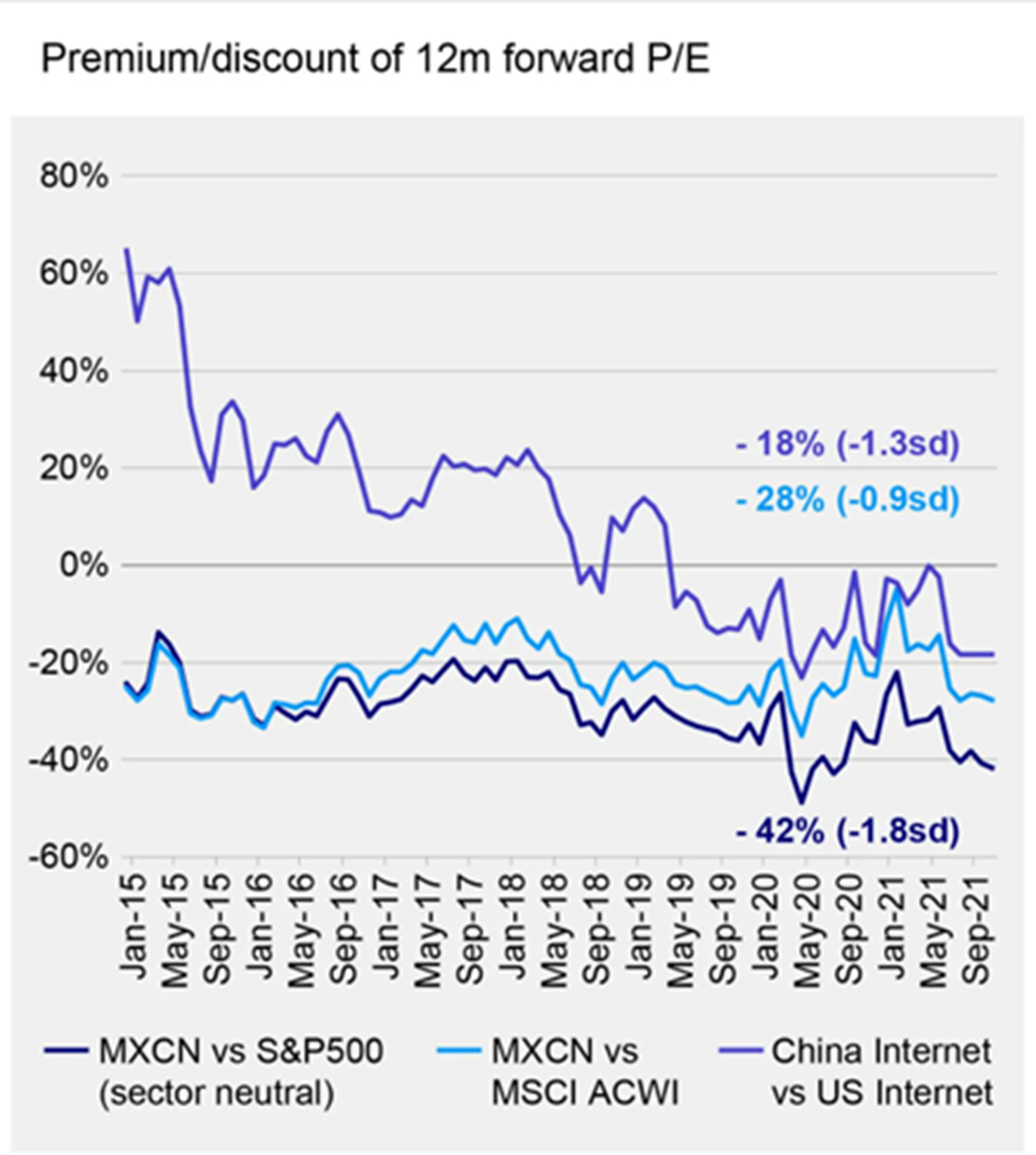

Source: Invesco, MSCI, FactSet

Dr. Xiaolin Chen, head of international at KraneShares, made the valuation case, pointing to US tech price-earnings ratios still at bubble levels while China’s internet sector sits at a ratio of 18x, shy of its five-year average.

Giving its view on the China tech outlook, JP Morgan’s China Market Outlook stated it expected China growth stock momentum would bottom out in Q4 2021, with policy “no longer restrictive”.

“Our economists were downgrading growth numbers for the Chinese economy throughout the second half of last year, but that appears to be stabilizing, as well. We are looking for a strong rebound in Chinese activity from the Q3 2021 low,” JP Morgan added.

Mainland vs offshore

Outside of how supportive policy will be to Chinese investors in 2022, another key debate has been around which type of Chinese equities to invest in – those listed in China, Hong Kong or even the US.

On the one hand, Chen argued offshore tech stocks faced an acute impact because of CCP regulatory action in 2021 and therefore “better performance catchup” potential going forward, given they start from a lower base.

However, Ahern noted there are tailwinds for China’s onshore listed equities such as the creation of the Shanghai Stock Exchange Science and Technology Innovation Board (STAR) in 2019.

“STAR was created as the venue for technology innovative companies to have a mainland listing. Historically, a lot of these companies went overseas because candidates have to be profitable to list in Shanghai and Shenzhen. The STAR board waives that requirement and allows these private companies to fund themselves through a mainland listing.”

He added, in November, mainland China shares were approximately 95% owned by Chinese investors, a margin that could increase with increased overseas involvement from foreign investors who usually favour H-Shares or American Depositary Receipts (ADR).

Agreeing, JP Morgan increased its 2022 long-term assumptions for China A-Shares returns by 0.3% in local currency and US dollar terms, respectively, and added it expects significant flows from both domestic and international investors.

It continued: “We believe investors do not have enough exposure to Chinese onshore assets; our hypothetical analysis finds that reallocating some holdings to Chinese onshore equities and government bonds would likely improve a multi-asset portfolio’s risk-adjusted returns.”

Fixed income and debt crisis

Interestingly, JP Morgan highlighted Chinese government bonds as an area that could offer investors a “substantial return premium” over developed markets as well as low correlations.

This chimes with asset flows in 2021, with investors piling $2.2bn into the largest Chinese bond ETF, the $13.5bn iShares China CNY Bond UCITS ETF (CNYB), over the past 12 months, as at 31 January.

Naturally, another conversation being had in Chinese fixed income surrounds the ongoing Evergrande debacle.

On this, Ahern told ETF Stream in November the government would not let the company fail because of its dependents, ranging from property-owners, workforces employed both internal and external to the firm, and bondholders.

“You extend the maturities, you cut the interest and you allow the company to muddle through and ride out the cycle. That is what we will see with Evergrande,” Ahern argued.

“Most of its debt is short (three to five years). Eventually, Evergrande in its present form will cease to exist – it will probably be broken down geographically and it will pay for the sins of its past. They are not going to let it outright default, at least that is the view in China. Some of the smaller property developers might go bankrupt.”

ESG progress in China?

Finally, a sensitive discussion for most investors – how much will China advance its ESG commitments?

JP Morgan started by praising the country’s efforts in recent years and pointed to how only 49% of companies in the China Securities index 300 filed ESG reports in 2010, versus 86% in 2020. A number, it said, would only increase as the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) increased reporting standards for onshore-listed companies.

On the environmental side specifically, Invesco’s Shiao pointed to China’s emissions trading scheme which launched last July and is already the largest in the world. Unfortunately, JP Morgan’s market outlook pointed to shortcomings in the scheme.

It said: “China’s ETS initially covers only the power sector, and China’s carbon price – $8 per tonne of CO2 – is far lower than Europe’s $63 per tonne. That gap, if not closed before 2023, will have to be paid for by Chinese steel, cement and aluminium manufacturers if they want to sell into Europe.”

Key in reducing China’s carbon output will be increased electrification of sectors including industrial, building and transportation, with state targets for electrification of energy use in these industries at 30% by 2030 and 70% by 2050. Key to the country’s broader electrification, Ahern argued, will be the rapid uptake of electric vehicles (EV).

“In 2020, EV made up around 5% of all auto sales and the policy is to try and get that up to 25% by 2025 and 40% by 2030. What we are hearing from some companies in the space is that might happen much faster than this,” he said.

However, Dzmitry Lipski, head of funds research at Interactive Investor, pointed to the seemingly intractable issue of Chinese companies operating in close proximity to human rights abuses.

“China may also be uncomfortable to hold, with human rights and democratic issues in Hong Kong a very serious case in point,” Lipski noted. “We support an active engagement approach through fund managers with strong expertise in the region, such as Fidelity, over ‘exclusion lists’. But this is a very personal issue.”

Overall, China’s ESG prospects, as with everything else, hinge on the party line of the CCP. Investors’ views on the government and what it will do next will be central to any portfolio construction exercise through 2022.

Related articles