European ETF participants often flatter to deceive by touting the industry’s 14% compound annual growth since 2010, however, just half of UCITS ETFs are currently in profit-making territory based on assets and fees, according to research by ETF Stream.

European-listed ETF assets under management (AUM) have increased eightfold from $208bn to $1.6trn over the past 13 years, but alongside organic asset-gathering, the ETF roster also doubled from 935 to 1852 over the period.

Analysis from Citi and HANetf revealed the annual operating cost of a UCITS ETF to be at least $200,000-$350,000.

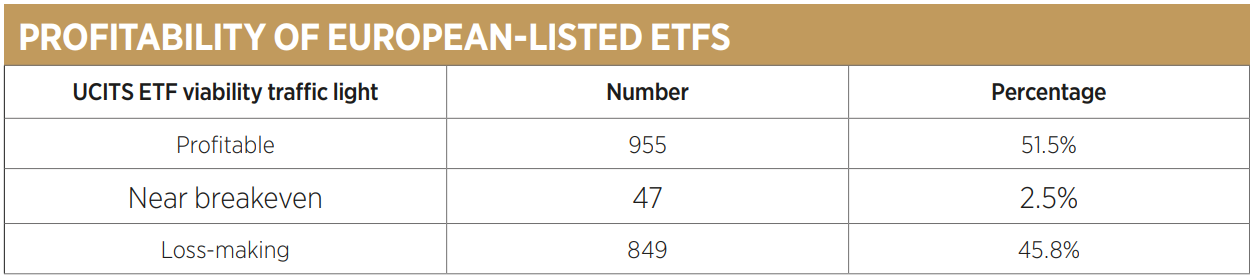

Based on data from ETFbook, just 955 – or 51.5% – of the current UCITS ETF line-up exceeds this range’s upper cost bound with revenues derived from total expense ratios (TERs) on their AUM.

The data also shows 174 – or 9.4% – of ETFs fall within the breakeven range and a considerable 721 – or 38.9% – are currently operating at a loss.

While some may think this paints a bleak picture, Henry Jim, ETF analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence, suggested a more ‘conservative’ lower bound for minimum operating costs for a single UCITS ETF should be set at $300,000.

Applying this more challenging cost estimate, just 47 – or 2.5% of – ETFs fall within the breakeven range while an eye-watering 849 – or 45.8% – lose money each year.

A murky cost landscape

It is worth noting there is a broad spectrum of potential costs for operating a UCITS ETF so the original cost range outlined by Citi for operating US-listed ETFs can only offer an indicative guide to viable products this side of the pond.

Jim added the breakeven range on UCITS ETFs can be as wide as $80,000 to $500,000 a year per product.

“Costs also depend on a whole range of variables including timing, where an ETF is filed, which umbrella it is under, distribution and more,” Jim concluded.

Ciaran Fitzpatrick, head of ETF solutions for Europe at State Street, argued several additional considerations for European ETFs see cost pressures mount.

“Additional listings and registrations, regulatory reporting in certain EU jurisdictions, payments to market makers – which is not permitted in the US – I would think the cost is certainly in excess of the minimum and maximum thresholds you have,” Fitzpatrick said.

“We continue to see ETF issuers in Europe drop their fees to better compete with other issuers. This means there is a huge focus on reducing these costs and the question as to buy, build or rent an ETF platform when entering the market.”

HANetf outlined three pillars of external costs involved in keeping the lights on in an ETF, excluding internal costs including portfolio management, marketing and distribution.

First, administration and custody costs paid to banks including State Street, BNY Mellon or JP Morgan, with these costs varying between provider based on scale and concurrent negotiating power.

Second, the cost of licencing the underlying index for passive ETFs can in some cases consume 50-60% of the revenue accrued from an ETF’s TER, with costs being higher for standalone strategies versus suites tracking iterations of the same exposure.

Third is the cost of running the ETF infrastructure, covering listing fees, registration and tax reporting.

Another worthy health warning is the fact not all revenue contributors to ETFs are included in our analysis – such as securities lending revenues – given the reduced visibility of this data across the roster.

Winners and losers

Highlighting some of the leaders and laggards, it will come as little surprise the $55.8bn iShares Core MSCI World UCITS ETF (SWDA) has the highest take of any ETF in Europe.

While smaller in size than BlackRock’s S&P 500 ETF, SWDA’s loftier 0.20% TER means it currently boasts $112m turnover per year, excluding securities lending revenues.

Outside of core equity, BlackRock also boasts the highest turnover in single fixed income and thematic strategies, with the $13.1bn iShares Core € Corp Bond UCITS ETF (IEAC) and $3.6bn iShares Global Clean Energy UCITS ETF (INRG) currently pulling in $26m and $23m a year, respectively, before costs.

However, BlackRock does not claim the crowns of highest-revenue smart beta or active ETFs.

Leading these packs, the $3.4bn Ossiam Shiller Barclays CAPE US Sector Value UCITS ETF (CAPU) and $3.2bn PIMCO US Dollar Short Maturity UCITS ETF (MINT) boast turnover of $22m and $11m, respectively.

Interestingly – excluding 2023 launches – the perception that more esoteric thematic ETFs launched by often smaller issuers are the least viable does not always ring true.

While much of the Europe-listed thematic ETF line-up sits below the breakeven threshold, the bottom end of the revenue table is populated by core exposures that have failed to fork any lightning.

Among these are the $1m SPDR MSCI USA Climate Paris Aligned UCITS ETF (SPUD), which launched in March 2022, and the $1m Invesco MSCI EMU ESG Universal Screened UCITS ETF (EEMU), which launched in March 2021.

The two ETFs currently book annual turnover of less than $2,000 apiece, excluding securities lending.

Meaningful outcomes

One of the key findings of our research is that large ETF issuers adopt a ‘supermarket’ approach, whereby they are willing to offer the full spectrum of ETF exposures, even with some operating at a loss, just to present themselves as one-stop-shops for their clients.

Manooj Mistry, COO at HANetf, said: “The larger issuers will always look at their range in a holistic way. They can charge six basis points on one ETF but make it back on their 60-basis point product.

“This supermarket approach gets investors through the door and means different parts of the product range can generate more or less revenue and generate a profit collectively.”

This is made possible by the fact many of the largest issuers are part of a larger asset manager or bank, meaning their costs are subsidised.

It also points to a key takeaway – competition is diminishing within European ETFs. Size and profitability matter for survivorship – and ETFs often only enter fund selector buy lists once they reach sufficient scale – meaning scale becomes scale. There is a risk the continued rise of large ETF providers is already self-perpetuating.

This article first appeared in ETF Insider, ETF Stream's monthly ETF magazine for professional investors in Europe. To access the full magazine, click here.