The new year is starting with one certainty: the normalisation of the yield curve is underway.

The reason is simple: central banks' focus turns from inflation to growth. That means that as inflation reverts to its mean, central banks will claim victory over inflation and will be more concerned about a deteriorating economy. That will call for interest rate cuts, precisely as the Federal Reserve's December dot plot shows. Therefore, it is safe to expect font-end rates to adjust lower, resulting in a steeper curve.

The big question, however, is what will happen to the longer part of the yield curve as central banks cut rates. When answering this question, it is impossible not to enter into a heated debate regarding some sort of landing:

A 'soft landing': Such a scenario implies that inflation reverts to its mean without a significant deceleration of the economy. In this case, the yield curve will bull steepen, but without a recession, the long part of the yield curve will remain around current levels or even move slightly higher.

A 'hard landing': Such a scenario implies a deep recession is upon us. That means the Fed might need to cut rates deeply and quickly. That would result in a steeper curve, with 10-year yields dropping sharply below 4%.

A '1970s landing': The fight against inflation is not over, and as geopolitical tensions intensify, inflation rebounds, resulting in a new inflation wave. Yet the economy stagnates, resulting in a flatter yield curve.

Although it is impossible to know which kind of landing we are headed towards, it is essential to recognise that the Fed can stimulate the economy through various policies beyond interest rate cuts, such as a slowdown or the early end of the quantitative tightening programme (QT).

QT is a powerful tool because it can be a substitute for interest rate cuts. Therefore, if a 'hard landing' does not materialise, bond futures must price out some of the six rate cuts that are baked in for this year.

Moreover, we must remember that the US Treasuries is poised to continue issuing large amounts of bonds and notes in the upcoming months, putting upward pressure on rates.

That means that if a recession is not around the corner and the economy continues to prove resilient, 10-year yields are more likely to move higher than lower in the upcoming weeks.

That is probably why Bill Gross said on X: "UST 10 yr at 4% is overvalued while 10-year TIP at 1.80 is the better choice. If you need to buy bonds. I don’t.”

When looking at the market's expectations for interest rate cuts, 10-year yields at 4% do not make sense because investors expect rates to decrease to 3.5% in the next 10 years. Considering that 10-year US Treasury offers between 100bps to 150bps over the Fed Fund rate from 2000 until today, their fair value should be around 4.5% to 5%. Yet, market expectations can change abruptly, especially during a downturn.

Therefore, we will likely see 10-year US Treasury yields rising slightly and trade rangebound for some time until the macroeconomic backdrop becomes clearer.

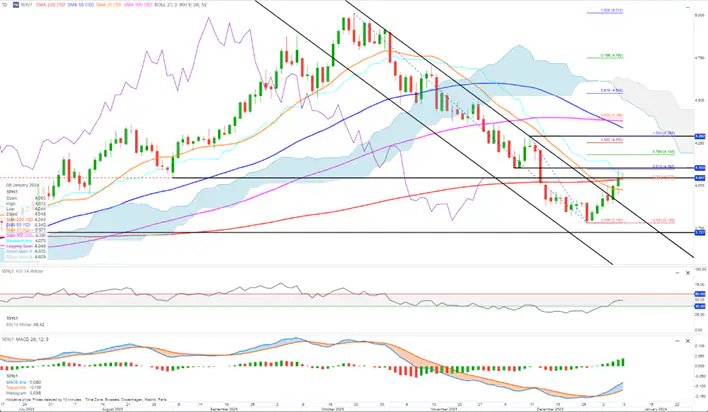

Currently, 10-year yields are trading slightly above 4%. If they break above 4.1%, they might find a new trading range between 4.1%- 4.3% (see Kim Cramer Larsson's technical analysis piece).

Chart 1: 10-year US Treasury yields

Source: Saxo Platform

Sovereign bonds remain attractive for long-term investors

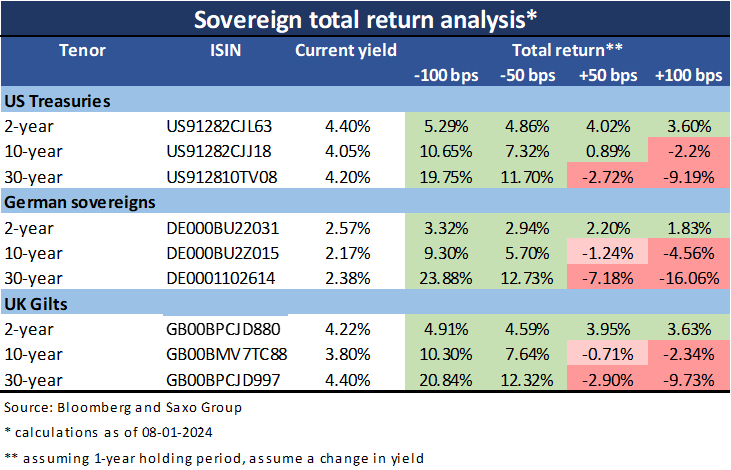

Even if yields rise in the medium term, sovereign bonds remain an attractive investment for buy-to-hold investors. Extending a portfolio duration is also compelling in light of deflationary trends and central banks' plans to cut rates.

Benchmark bonds issued during the last Treasury quarterly refunding offer a coupon that creates a buffer against a possible drop in price. The 10-year tenor looks particularly compelling. Assuming a one-year holding period, if yields rise by 100bps, the loss that one would expect is a little above 2%.

As we learned last year, 5% is a strong resistance level for 10-year US Treasuries. If yields could not break above this level when it was uncertain whether the Fed was done with its interest rate hiking cycle, it is hard to envision they would even rise around this level now that central banks are preparing to cut rates on both sides of the Atlantic.

Althea Spinozzi is senior fixed income strategist at Saxo Bank